Canine Parvovirus Monoclonal Antibody and Length of Treatment, Cost of Treatment, and Mortality in A Shelter Setting

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v4.159Keywords:

canine, parvovirus, monoclonal, antibody, cost of care, animal shelterAbstract

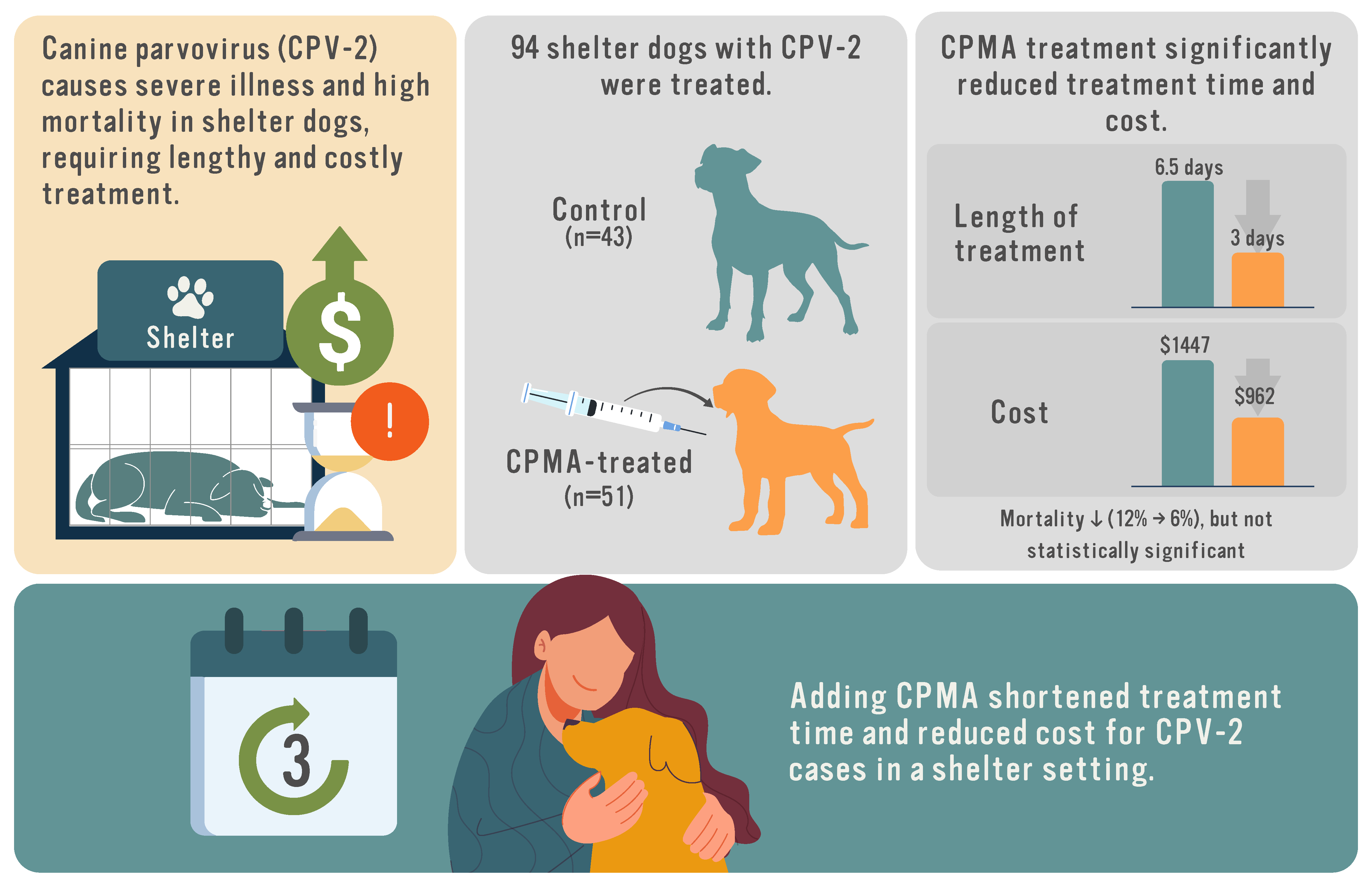

Introduction: Canine parvovirus (CPV-2) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in dogs, with often lengthy and expensive treatment that can still end in fatality. In a shelter setting, the length and cost of treatment are important and related factors in being able to provide care for dogs affected with CPV-2. This study examined the addition of canine parvovirus monoclonal antibody (CPMA) to an established treatment program on the length of treatment, cost of treatment, and mortality in a shelter setting.

Methods: This retrospective observational study examined 94 cases of parvovirus diagnosed via IDEXX SNAP testing in a limited admission shelter between the years 2022 and 2024. All cases were treated with the shelter’s standard parvovirus treatment protocol, and 51 of those cases additionally received CPMA. The median length of treatment, average cost of treatment, and mortality rate were compared between those treated with CPMA versus those that were not.

Results: Of the 94 cases examined, 43 were not treated with CPMA and 51 were. The median length of treatment of the CPMA group was 3 days (95% confidence interval, CI [3.3–4.5]) compared to 6.5 days (95% CI [5.5–7.4]) for the control group, a significant decrease for dogs treated with CPMA. The average cost of treatment for the CPMA treated group was $962 (95% CI [$848–$1,140]) compared to $1,447 (95% CI [$1,243–$1,658]) for the control group, also showing a significant decrease. The mortality rate of the CPMA treated group was 6% compared to 12% for the control group; this was lower but ultimately not statistically significant.

Conclusion: The addition of CPMA to established treatment plans for CPV-2 was associated with a significant decrease in the length and cost of treatment, but no significant decrease in the mortality rate.

Downloads

References

1.

Mylonakis M, Kalli I, Rallis T. Canine Parvoviral Enteritis: An Update on the clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Vet Med Res Rep. 2016;7:91–100. doi: 10.2147/VMRR.S80971

2.

Goddard A, Leisewitz AL. Canine Parvovirus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010;40(6):1041–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.07.007

3.

Crawford C. Canine and Feline Parvovirus in Animal Shelters. Presented at: Western Veterinary Conference. Las Vegas, NV; 2010. Accessed Aug 05, 2025. Available from: https://diasystemvet.se/documents/[Academic]%20Canine%20and%20Feline%20Parvovirus%20in%20Animal%20Shelters.pdf.

4.

Pasteur K, Diana A, Yatcilla JK, Barnard S, Croney CC. Access to veterinary Care: Evaluating Working Definitions, Barriers, and Implications for Animal Welfare. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11:1335410. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1335410

5.

Larson L, Miller L, Margiasso M, et al. Early Administration of Canine Parvovirus Monoclonal Antibody Prevented Mortality after Experimental Challenge. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2024;262(4):506–512. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.09.0541

6.

Zhan H, Nguyen L, Ratcliff E, Chin R, Li S. US patent application No. 17/630,685. 2022.

7.

Horecka K, Porter S, Amirian ES, Jefferson E. A Decade of Treatment of Canine Parvovirus in an Animal Shelter: A Retrospective Study. Animals. 2020;10(6):939. doi: 10.3390/ani10060939

8.

Perley K, Burns CC, Maguire C, et al. Retrospective Evaluation of Outpatient Canine Parvovirus Treatment in a Shelter-Based Low-Cost Urban Clinic. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2020;30(2):202–208. doi: 10.1111/vec.12941

9.

Herron ME, Kirby-Madden TM, Lord LK. Effects of environmental Enrichment on the Behavior of shelter Dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244(6):687–692. doi: 10.2460/javma.244.6.687

10.

Venn EC, Preisner K, Boscan PL, Twedt DC, Sullivan LA. Evaluation of an Outpatient Protocol in the Treatment of Canine Parvoviral Enteritis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2017;27(1):52–65. doi: 10.1111/vec.12561

11.

Ling M, Norris JM, Kelman M, Ward MP. Risk Factors for Death from Canine Parvoviral-Related Disease in Australia. Vet Microbiol. 2012;158(3–4):280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.02.034

Additional Files

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Stefanie Hornback, Emily Ferrell

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.