ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

A Retrospective Study of Cat Hoarding Cases and Their Management Through Voluntary Spay/Neuter and Relinquishment In New York City

Biana Tamimi, Emily Dolan, Lisa Kisiel, Elizabeth Berliner

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, New York City, NY USA

Abstract

Introduction: Animal hoarding cases are complex sources of shelter intake. Cases require significant planning, collaboration, and resources, often from multiple responding organizations. Study objectives included description of cat hoarding cases in New York City not criminally pursued, case outcomes when managed by a spay/neuter and relinquishment program utilizing a collaborative approach with caregivers, and characteristics or interventions leading to better outcomes.

Methods: Data were extracted from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animal’s Community Engagement (CE) case files. Eligible cases were retrieved using a keyword search and screened for inclusion criteria. Client demographics, case factors, and outcomes were described with descriptive statistics. Data were further analyzed using adjusted logistic regression models to investigate variables predictive of outcomes.

Results: The study population included 79 cases with a median population size of 22 cats. The majority of clients were female, lived alone, and had high levels of social vulnerability. Object hoarding was reported in 29.1% of cases and unsanitary conditions in 68.4% of cases. Almost one-third (30.4%) identified as rescuers or community cat caregivers. At the time of the first interaction with CE, 88.6% of clients were interested in spay/neuter and 76.0% in surrender services. Social service agencies were involved in the initial CE intervention in 26.4% of cases.

Successful outcomes were defined as cases in which clients were left with a manageable population of cats, or all cats were removed. Successful outcomes were achieved in 67.1% of cases after the first CE intervention. Recidivism occurred in 41.5% of these cases. Clients who showed an initial interest in surrender were 10 times more likely (OR 10.0, P = 0.014) to experience a successful outcome than clients not interested in surrender. Significant predictors of re-collection included clients identifying as rescuers (OR 4.8, P = 0.039) and the involvement of human service agencies during or after the CE intervention (OR 6.1, P = 0.041).

Conclusion: Results demonstrate animal hoarding cases involving cooperative caregivers and rescuers can be successfully managed by programs using a collaborative approach with clients. The high rates of initial interest in spay/neuter and surrender in caregivers suggest a need to expand access to veterinary care and strategically manage case intake into shelters. Further interdisciplinary research is needed on how mental health, social service, and animal service providers can attain successful outcomes long-term and reduce recidivism in animal hoarding cases.

Keywords: animal hoarding; access to care; humane investigations; harm reduction; social vulnerability index

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2024, 3: 92 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v3.92

Copyright: © 2024 Biana Tamimi et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 2 May 2024; Revised: 1 June 2024; Accepted: 1 June 2024; Published: 5 August 2024

Reviewers: Jacklyn Ellis, Courtney Graham

Correspondence: *Biana Tamimi (ASPCA), 424 E. 92nd St., 10028 New York City, NY USA. Email: Biana.tamimi@aspca.org

Competing interests and funding: No external funding was used in this study. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Animal hoarding was first described in scientific literature in 1981 using data from New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA).1 Since then, despite being found in many communities around the world,2–11 animal hoarding continues to be a poorly researched phenomenon affecting public health, animal welfare, and the myriad of responding organizations.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines animal hoarding as a ‘special manifestation’ of object hoarding disorders characterized by the accumulation of a large number of animals, failure to provide minimal standards of care, and failure to recognize and act on deteriorating conditions of the environment and animals.12 Overlap exists between hoarding and addiction, obsessive compulsive, and attachment disorders.12,13 One study demonstrated that individuals who hoarded animals over 20 years had a higher occurrence of bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosis, and memory deficits.14

Management strategies have largely depended on the severity of conditions and degree of cooperation from the affected individual. People who hoard animals have been categorized into three main types: the overwhelmed caregiver, the rescue hoarder, and the exploiter hoarder.13,15,16 Overwhelmed caregivers acquire animals passively and often have strong attachments to their animals, but changes in economic, domestic, or medical circumstances result in a reduced ability to meet animal needs and control reproduction.16,17 Both rescue and exploiter hoarders actively acquire animals; however, although rescue hoarders may fail to recognize suffering and avoid authorities, exploiter hoarders demonstrate profound lack of empathy and are more likely to become combative when confronted.15 Cases involving rescue and exploiter hoarders tend to have larger numbers and more severely compromised animals and are more likely to require legal prosecution.16 While hoarding situations can include any number of animals (from as few as 5 to well over 500 animals),17 the current literature has focused on larger-scale cases involving over 40–50 animals.5,8–10,18–20 There is little published information on smaller-scale cases, particularly those associated with a collaborative approach involving voluntary engagement and relinquishment by caregivers.21,22

Although animal hoarding occurs across demographic and socioeconomic boundaries,16,19,20 studies have demonstrated that the majority of individuals are female, middle-aged or elderly (ranging in age from 51.8 to 94 years), and live alone.1,5,6,8,9,14,15,19,20,23–27 Recent studies from Brazil and England suggest that animal hoarding may occur more frequently in areas with higher levels of social vulnerability.8,27 Social vulnerability refers to a community’s susceptibility to experiencing the negative effects of external stressors on human health, including natural and human-caused disasters or disease outbreaks.28 While the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) has not been applied to animal hoarding before, SVI is used in other health contexts to assess a community’s relative social vulnerability by examining aggregated social factors from census tract (or county) data. These factors include socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status and language, and type of available housing and transportation.28 The SVI ranking of a census tract (or county) is reported on a scale of 0 (least vulnerable) to 1 (most vulnerable), indicating the percentage of tracts nationwide that have an equal or lower social vulnerability.28 For example, a census tract with an SVI ranking of 0.85 is more socially vulnerable than 85% of tracts and therefore less vulnerable than 15% of tracts.

A systematic review reported recidivism rates in animal hoarding cases range from 13 to 41% following interventions,23 although reports on animal hoarding frequently cite that recidivism approaches 100%.15,17 Given the presence of mental health concerns, social isolation, unstable personal circumstances, and unsanitary living conditions, the welfare of animals being hoarded and the well-being of humans involved are interlinked. Therefore, a One Welfare approach that recognizes these interconnections and utilizes collaborative intervention strategies between human and animal agencies may better address human well-being long-term and prevent recidivism.13,15,17,29,30

Animal hoarding, by definition, involves varying degrees of neglect, which can potentially constitute animal cruelty under New York state law31; however, cases can be challenging to address through the criminal justice system. When caretakers are elderly, have mental health concerns, or are from other vulnerable populations, a punitive approach is not always appropriate or effective in leading to meaningful interventions. It may also be more desirable to intervene before a situation escalates and is criminally actionable. In some US states, alternatives to criminal prosecution include use of civil mechanisms that require caregiver compliance in these cases; however, a civil process is not currently available in New York. Particularly in less severe cases involving cooperative caregivers from vulnerable populations, animal hoarding may be more appropriately and expeditiously managed by non-judicial interventions outside of court proceedings.15,17,20

Harm reduction refers to a range of interventions and policies that diminish the negative impacts of various complex human behaviors that are unlikely to resolve.32,33 While historically used in the context of drug use, a harm reduction intervention model can be applied to individuals who hoard animals.17 Given the high rate of recidivism, a human-centered harm reduction approach that utilizes frequent check-ins with clients, assistance with spay/neuter and surrender, and collaborative engagement with social services may be effective.13,17 However, currently little is known about the impact of voluntary spay/neuter and relinquishment programs on animal hoarding case outcomes.21

The main objective of this study was to describe cat hoarding cases not pursued criminally in New York City from 2011 to 2023 but instead managed by a program that utilizes a collaborative approach with caregivers. A secondary aim was to identify client and case factors associated with successful outcomes and recidivism to help guide decision-making and target interventions in hoarding case management.

Methods

Study population

The ASPCA Community Engagement (CE) program aims to improve both animal welfare and human well-being by keeping pets and people together whenever possible and appropriate. The program assists clients with supplies and equipment (food, leashes, and crates), veterinary care, grooming, and other services. Clients are referred to the program (e.g. by social service agencies, law enforcement, shelter partners, and concerned citizens) and voluntarily engage. Central to CE’s work is collaborative goal setting with clients; clients can decline services at any point. However, when conditions rise to the level of animal cruelty and clients are uncooperative, cases may be referred to law enforcement.

Hoarding cases managed by CE are approached through a lens of harm reduction when caregivers are willing to engage. CE coordinators evaluate the animals and home environment using an internal assessment tool based on the Five Freedoms.34 Coordinators work with caregivers to achieve mutual goals, which may include returning some animals to the home after spay/neuter and surrendering others. Interventions are often staged depending on surgery and shelter capacity and the client’s willingness to engage. Additional human or animal agencies are contacted as needed. A case is closed by CE when goals are met, or the client becomes uncooperative or declines services, at which point severe cases may be referred to law enforcement for management. Records of communications and interventions are maintained in an electronic database.

Case selection

This study provides a retrospective, secondary data analysis study of case records from the ASPCA’s CE team in New York City between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2023. The study protocol was approved by the ASPCA’s internal ethical review for animal research and exempt from Institutional Review Board oversight (under 45 CFR 46.104(d) (4)).

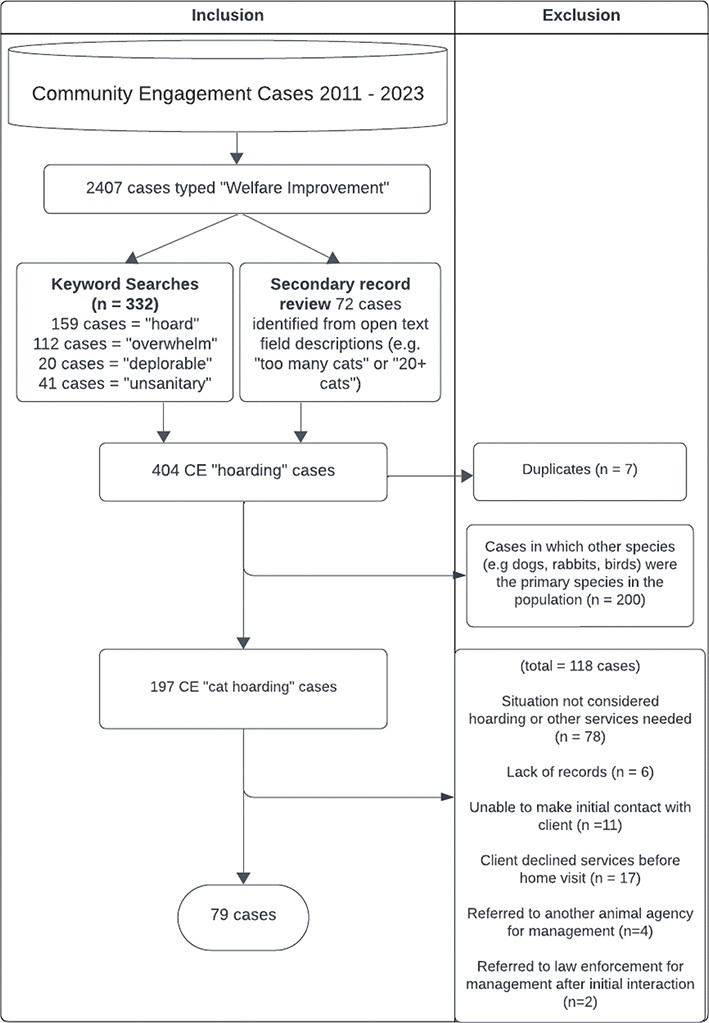

All data were extracted from existing case files in the CE database in the software Neon CCM (NeonOne, LLC, 2024). All hoarding cases were typed ‘Welfare Improvement’ cases by CE; this descriptor was also used for non-hoarding cases needing other services (e.g. end of life care, medical or husbandry supplies, or grooming). A list of all ‘Welfare Improvement’ cases (n = 2,407) was generated and exported to Excel (Microsoft Corporation, version 16.16.27, 2018). This case list included case numbers and the chief complaint, presenting concern or reason for referral. This list was further searched using keywords (see Fig. 1), and a secondary review was performed for cases suggestive of hoarding situations (e.g. ‘large number of cats’ or ‘over 20 cats in terrible condition’). Qualifying case records were further reviewed to assess eligibility for study inclusion, with reasons for exclusion reported in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of selection process of cat hoarding cases managed by a voluntary, collaborative intervention program in NYC.

A total of 79 cases were included in this study. Additional data were then pulled from database case files including client demographics (Table 1), case factors (Table 1), and outcomes. Client SVI was collected from U.S. Census tract data available from the CDC website.28

| Factor Type | Variable | Definition |

| Client factors | Borough | New York City borough (area) |

| SVI | CDC Social Vulnerability Index | |

| Gender | Self-reported gender when provided, otherwise gender as reported by social service agency or CE caseworker | |

| Elderly | Reported by social service agency or CE caseworker to be ‘elderly’ | |

| Mental or physical disability | Reported by social service agency to have a mental or physical disability, or CE caseworker identified signs suggestive of a mental or physical disability | |

| Friend or family member facilitating intervention | A friend or family member was the main point of contact for the intervention | |

| Already has a social worker | The client already has a social worker involved in the case | |

| Rescuer or community cat caregiver | Client self-identified as a rescuer or community cat caregiver and was reported to actively acquire animals. | |

| Unsanitary conditions | Report of squalor or unsanitary conditions in the hoarding environment | |

| Object hoarding | Report of object hoarding present in the animal hoarding environment | |

| Lives alone | Client is the sole occupant in the primary housing unit | |

| Initial interest in spay/neuter | Client showed interest in spay/neuter during their first interaction with CE | |

| Initial interest in surrender | Client showed interest in surrender during their first interaction with CE | |

| Case factors | Source of referral | Organization or person who referred the case to CE, as categorized by CE. Note: referrals from law enforcement are included in the Social service agency source category as per CE. |

| Number of cats | Total number of cats in the population being hoarded | |

| Number of days case open | The number of days from the date of the first interaction with the client (contact was made) until the date the case was formally closed in the software | |

| Presence of ringworm* | CE was aware of ringworm in the population at the time of the intervention | |

| Other animal service agency involved during initial intervention | Another animal service agency was involved in the initial intervention | |

| Human service agency involved during initial intervention | A human service agency (excluding law enforcement) was involved in the initial intervention | |

| Referred to a human service agency after initial intervention | The case/client was referred to a human service agency (excluding law enforcement) by CE after the intervention | |

| Human service agency involved during or referred after initial intervention** | A human service agency was involved during the initial intervention, or the case/client was referred to a human service agency by CE after the initial intervention (Human service agency involved and Referred to a human service agency after intervention are aggregated) | |

| Eviction notice | The client had a pending eviction notice or was facing eviction by their landlord | |

| *While examining the medical conditions of cats was outside the scope of this study, ringworm is included in results due to its public health implications and the additional challenges posed to case management regarding biosecurity and shelter capacity. | ||

| **Variable only examined in Table 5. | ||

Outcome analyses included whether or not (1) cases were successful after the first intervention, (2) re-collection occurred after an initial successful intervention, and (3) the client sought spay/neuter or surrender services after an unsuccessful first intervention.

For the purposes of this study, ‘successful’ case outcomes were defined as results in which one of the following population-level situations was achieved following CE’s interventions:

- The client was left with a population of altered or unaltered same-sex animals they could effectively manage.

- All animals involved in the case had been removed from the hoarding environment (e.g. surrendered to a shelter).

‘Re-collection’ occurred when clients actively obtained more cats following a successful outcome.

No set timeframe was applied to determine case outcomes within the study period. For example, clients could have re-collected at any point from the time the case was closed until records were reviewed on December 31st, 2023.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were produced using Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses to determine relationships between client and case factors and outcomes were carried out using Stata (StataCorp, version 17.0 Basic Edition). Associations were initially explored between case outcomes and variables using Fisher’s exact tests (for categorical variables) and T-tests (for continuous variables).

To further explore these interactions and hold predictive variables constant, an adjusted model was used to investigate any predictors of case outcomes. Two logistic regression models were applied to a focused selection of client and case variables for two outcomes (i.e. cases that were successful after the first intervention, and cases re-collected following a successful initial intervention). The significance level for statistical analysis was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Client and case characteristics

Cat hoarding cases in this study were primarily located in the New York City boroughs of the Bronx (34.2%), Queens (26.6%), and Brooklyn (17.7%) (see Table 2). The average (mean) overall SVI of clients experiencing hoarding was 0.76 (SD = 0.18). The majority of clients were female (76.0%) and lived alone (68.4%). Clients also were noted to be elderly (32.9%), have a mental or physical disability (43.0%), and identify as a rescuer or community cat caregiver and actively acquire cats (30.4%).

Squalor or unsanitary conditions were noted in 68.0% of the cases, and object hoarding was reported in 29.1% of cases. Case records demonstrated that at the time of the first interaction with CE caseworkers, 88.6% of clients were interested in spay/neuter, and 76.0% were interested in surrender services.

The most common sources of case referrals were concerned citizens or neighbors (26.6%), shelter organizations (21.5%), and social services agencies (16.5%) (see Table 3). The median number of cats per case was 22 (range 5–70).

Animal service agencies other than the ASPCA were involved in 32.0% of cases. Human service agencies were involved in the management of 26.7% of cases. An eviction notice was pending in 15.2% of cases. The CE team referred 26.6% of clients to social service agencies during or after the first intervention. The median number of days cases were open and in the process of being managed was 77 days (range 2–638).

Case outcomes

A successful outcome was achieved in 53 of 79 (67.1%) cases after the CE team’s first intervention (Table 4). Twenty-six of 79 (32.9%) cases were considered unsuccessful following the initial intervention due to loss of contact with the caregiver (11/26) or noncompliance and rejection of services after initial interest (15/26). Re-collection was reported in 22 of the 53 (41.5%) cases initially considered successful. Of the 26 cases with unsuccessful initial outcomes, 15 clients (57.7%) reached back out to the CE team for services including spay/neuter and surrender.

Interactions between client and case characteristics and case outcomes

Preliminary analysis showed associations between successful initial outcomes and the client’s interest in population reduction: cases in which clients had initial interest in spay/neuter (P < 0.01) or surrender (P < 0.01) were associated with successful outcomes. Clients who did not identify as rescuers or community cat caregivers were also associated with successful outcomes (P = 0.04). Cases requiring human service agency involvement during or after CE intervention were associated with re-collection (P = 0.05). Additionally, cases that re-collected had a significantly larger number of cats (mean 33.2 cats, SD = 13.13, P = 0.05) than those who did not re-collect (mean 23.7 cats, SD = 14.53). Cases that re-collected were also open for a significantly (P = 0.028) longer period of time (mean 344.9 days, SD = 614.96) than cases that did not re-collect (mean 117.8 days, SD = 123.95).

Multivariate logistic regression modeling of the client and case characteristics found that initial interest in surrender was a significant predictor of successful case outcomes. Cases in which clients showed an initial interest in surrender were 10 times more likely (P = 0.014) to have a successful outcome than cases with clients that were not.

Predictors of re-collection following an initial successful outcome included clients identifying as rescuers, the involvement of human service agencies during or after CE intervention, and the number of days the case was open (Table 5). Clients who identified as rescuers or community cat caregivers were five times more likely (P = 0.039) to re-collect after achieving a successful initial outcome than cases with clients who did not identify as rescuers. Cases involving or referred to human services by CE were six times more likely (P = 0.041) to re-collect after a successful initial outcome than cases not involving human service agencies. For every additional day, a case remained open, the odds of re-collection after an initial successful outcome increased by 1.007 (P = 0.031).

| Factor type | Variable | Successful initial outcome | Re-collected after an initial successful outcome | ||||||||

| P | Odds ratio | Standard error | 95% confidence interval | P | Odds ratio | Standard error | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| Low | High | Low | High | ||||||||

| Client factors | Gender | 0.866 | 1.1505 | 0.9544 | 0.22633 | 5.8481 | 0.177 | 5.721909 | 7.3931 | 0.4547 | 72.004 |

| Elderly | 0.305 | 2.2303 | 1.74416 | 0.48162 | 10.328 | 0.849 | 0.856778 | 0.6942 | 0.1751 | 4.1929 | |

| Mental or physical disability | 0.438 | 0.5455 | 0.42648 | 0.11787 | 2.525 | 0.473 | 1.731112 | 1.3234 | 0.3869 | 7.7455 | |

| Friend or family member facilitating | 0.655 | 1.467 | 1.25747 | 0.2734 | 7.8715 | 0.61 | 0.611071 | 0.5905 | 0.092 | 4.0604 | |

| Rescuer or community cat caregiver | 0.198 | 0.4001 | 0.28491 | 0.09912 | 1.6154 | 0.039* | 4.792769 | 3.6346 | 1.0841 | 21.189 | |

| Unsanitary conditions | 0.645 | 1.6723 | 1.86477 | 0.18798 | 14.876 | 0.341 | 0.420504 | 0.3827 | 0.0706 | 2.503 | |

| Presence of object hoarding | 0.142 | 0.2538 | 0.23678 | 0.04077 | 1.5799 | 0.115 | 3.313955 | 2.5203 | 0.7464 | 14.713 | |

| Lives alone | 0.665 | 1.4278 | 1.17471 | 0.28468 | 7.1611 | 0.88 | 1.124882 | 0.8759 | 0.2451 | 5.1751 | |

| Initial interest in spay/neuter | 0.066 | 9.4729 | 11.5809 | 0.86271 | 104.02 | 0.893 | 0.831161 | 1.141 | 0.0564 | 12.253 | |

| Initial interest in surrender | 0.014* | 9.987 | 9.32575 | 1.60175 | 62.27 | 0.707 | 1.433743 | 1.3729 | 0.2195 | 9.3661 | |

| Number of cats | 0.54 | 0.9831 | 0.27372 | 0.93087 | 1.0382 | 0.059 | 1.048932 | 0.0266 | 0.9982 | 1.1023 | |

| Case factors | Number of days case open | 0.24 | 1.0016 | 0.00128 | 0.99899 | 1.004 | 0.031* | 1.006556 | 1.141 | 0.0564 | 12.253 |

| Human service agency involved during initial intervention | 0.539 | 0.56 | 0.52881 | 0.088 | 3.5642 | 0.704 | 0.734537 | 0.5957 | 0.1499 | 3.5997 | |

| Human service agency involved during or after initial intervention | 0.438 | 2.5342 | 2.42971 | 0.387 | 16.594 | 0.041* | 6.143931 | 5.4646 | 1.0749 | 35.118 | |

| *Statistically significant predictor of case outcomes (P < 0.05). | |||||||||||

Discussion

Client and case characteristics

The majority of clients in this study were cooperative, overwhelmed caregivers due to the voluntary nature of the CE program’s approach. However, 30.4% of clients self-identified as rescuers or community cat caregivers and were reported to actively acquire animals. Although initial willingness to engage with responding agencies is not typically considered a characteristic of rescue hoarder types,13,15,16 the majority of clients in this study were interested in reducing their population size at initial interaction (spay/neuter (88.6%), surrender services (76%)). The high rate of willingness to engage with services and the smaller average cat population size in this study (median 22 cats) suggest that clients identifying as rescuers demonstrated characteristics of overwhelmed caregivers. This finding may indicate that rescuer hoarder types can be successfully managed by intervening agencies in a similar, collaborative manner to overwhelmed caregivers. None of the cases were considered ‘exploiter hoarders’ or individuals breeding animals for sale, as those cases were not referred to CE or were redirected by CE to law enforcement agencies (n = 2, Fig. 1).

The majority of clients in this study were female and lived alone, which aligns with previous reports.1,5,8,9,14,15,19,20,23–27 Consistent with the literature, unsanitary living conditions or squalor and object hoarding were present and posed a public health concern for affected individuals.8,12,24,35 Over 78% of clients in this study lived in the three most socially vulnerable counties (Kings, Queens, and Bronx) in New York City. The average client SVI was 0.761, indicating a high level of overall social vulnerability. SVI considers aggregated social factors from census tract (or county) data, including socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status and language, and type of available housing and transportation.28 SVI has not specifically been applied to animal hoarding reports previously. Several studies indicate that while animal hoarding occurs in individuals from all levels of social vulnerability,17,20,24 it occurs with higher frequency in areas with greater social deprivation.5,8,10,27

Numerous studies suggest animal hoarding by overwhelmed caregivers correlates with a traumatic change in circumstance, such as a physical illness or disability.12–14,16,17,20 CE case records indicated 43% of caretakers were either reported by a social service agency to have a physical or mental disability or the CE program reported the client to have signs consistent with a disability. The CE program does not utilize a standardized mental health assessment; therefore, these records likely do not reflect the true prevalence of physical or mental disability.

As described by the One Welfare framework, the welfare of hoarded animals suffering from neglect is interlinked with the well-being of the humans involved.29,30 Given that animal hoarding is a diagnosable mental health condition12 associated with a plethora of social welfare and public health issues, animal agencies alone lack the resources to address the underlying causes and meet human needs both short and long-term. A harm reduction approach utilizes collaboration between individuals and animal and human service agencies to reduce negative consequences and maximize positive outcomes while accepting that comprehensive resolution of issues is complex and unlikely to be attained.13,15,17 In this study, only 16% of clients hoarding animals were already working with a social service agency. However, a total of 53.2% of cases required social service agency involvement during or after case management. Animal welfare organizations directly increasingly employ social and mental health workers in their programs so clients can more easily access the support systems they need.36–38

The primary sources of referral for study cases included neighbors, anonymous concerned citizens, animal welfare organizations, social service agencies, and law enforcement; these sources are consistent with sources previously described in the literature.5,11,23,24 This diversity of referral sources demonstrates animal hoarding is a community-wide concern, requiring vigilance and knowledge of programs poised to respond to animal hoarding situations. The high number of referrals from neighbors or concerned citizens (26.6%) suggests it would be beneficial for responding organizations to have readily available material and resources for community members on how to recognize and report suspected hoarding cases. Distributing resources on collaborative intervention services can prevent under-reporting by community members concerned with punitive approaches, especially when individuals are elderly or members of other vulnerable populations. Educational resources can also destigmatize overwhelmed cat owners and connect struggling caregivers with needed services.

Case and client characteristics and outcomes

The nature of the CE program selects for less severe animal hoarding cases in which caregivers are amenable to assistance. This willingness to engage is reflected in the findings, with only 17 of 197 cases (8.6%) excluded from the study because services were declined during initial contact before a home visit could be made (Fig. 1).

Initial interventions resulted in voluntary reduction or removal of populations of cats in 67.1% of cases. However, 41% of these clients demonstrated some degree of re-collection during the study period. Of the cases that were unsuccessful after the first intervention (and therefore closed), over half (57.7%) of these clients reached back out to CE for spay/neuter or surrender services. However, the amount of time that passed after cases were closed varied greatly because of the timeframe of this study, leaving some cases less time to demonstrate their ultimate outcomes. Further studies with extended follow-up may provide a more accurate assessment of outcomes.

For both overwhelmed caregivers, who initially acquire animals passively, and rescuers who actively bring cats into the household, subsequent uncontrolled breeding can tip a population size that is manageable into one that is too large to be effectively cared for. While the exact reasons for accumulating cats were not specified in the study records, a lack of access to spay/neuter services likely contributed to hoarding situations. The high level of interest in spay/neuter during the first interaction with CE (88.6%) suggested clients (even rescuers) recognized the safety and importance of spay/neuter and caregivers and would likely proceed with surgery if services were more easily accessible. Initial interest in spay/neuter was associated with successful outcomes in the pairwise model, although this was not significant in the adjusted analysis model. Accessible sterilization programs could play a role in hoarding prevention. To reduce the gap in access, programs should reduce or eliminate as many key barriers to access as possible, including financial, language, transportation, and other logistical barriers.39 Additionally, veterinary resources are less accessible in areas with greater levels of social vulnerability (higher SVI) and veterinary deserts, and locating services in these areas could provide highly effective at reducing inequities in access.40,41 Strategic support and resources for spay/neuter programs – including promotional materials, pathways to obtain these services, and subsidized costs – could serve to further increase client awareness of and access to services.

Clients were initially interested in surrender in 76% of cases. Clients expressing interest in reducing their population were 10 times more likely to experience a successful outcome after the first intervention. Often, the best outcomes for the majority of animals in hoarding situations include removal from the hoarding environment to meet their physiological, medical, and behavioral needs. However, sudden large intakes of hoarded animals strain shelter resources, including financial, housing, foster, and medical.

Intra-agency collaboration can aid various responders (i.e. law enforcement, human service agencies, and shelters) to strategically ensure the well-being of case animals, and animals already housed in the shelter are not further compromised by the response. For example, to accommodate large intakes, shelters can partner with other animal welfare agencies to expand placement options and share resources. Additionally, shelters can apply for assistance from grant providers and appeal to municipalities for fair contracts or allocation of resources. State laws should provide a clear and meaningful way for shelters to alleviate financial challenges in cases requiring legal seizure of animals by implementing effective cost of care laws, which provide a judicial mechanism for requiring owners to pay to house and care for their animals.

In an effort to operate within their capacity for care while still being able to respond to hoarding cases, shelters can also utilize managed admissions policies and other population management strategies.42,43 Managed intake approaches to hoarding cases may include providing services in situ, such as the provision of on-site triage, mobile spay/neuter, and selective removal of animals based on shelter capacity and adoptability. These interventions are dependent on the environmental conditions, the animals’ health and welfare, and the relationship with the client and, therefore, may require support from multiple agencies. To better understand the long-term impact of managed admissions on hoarding situations and guide decision-making, future studies could investigate case outcomes and management strategies involving partial and full removal of animals.

The recidivism rate in this study (41.5%) was comparable to that described in the literature.6,9,20,23,27 Cases in which clients self-identified as rescuers were five times more likely to re-collect after an initial successful outcome. This finding is consistent with the literature describing rescue hoarders as collecting animals from a mission-based idealized identity,15,16,44 which is noted to more likely to result in recidivism.17 Due to the time period for follow-up in this study, the true recidivism rate could be higher.

An unexpected finding was that cases that involved or were referred to human services by CE after an initial intervention were six times more likely to re-collect than cases not involving human service agencies. On the surface, this finding might imply that inter-agency collaboration is not effective; however, early referral to other social service agencies is likely biased toward more complex cases also more likely to re-collect. Literature states that complex cases with severe mental or physical health concerns generally require greater and ongoing support from multiple sectors or rise to the level of legal proceedings.13,15

Currently, in New York state, legal mechanisms to compel non-cooperative animal hoarders to reduce the numbers of animals in their care or otherwise improve conditions are limited. Being absent in the appointment of a legal guardian, who can make decisions regarding the animals on behalf of the owner, the animals need to be legally seized in connection with a criminal investigation and prosecution. In many cases, this punitive approach is not ideal, given many clients struggle with a myriad of social, economic, and mental health challenges. In addition, some situations may not rise to a level that law enforcement can pursue criminally. A civil process by which law enforcement agencies can initiate a non-criminal process to address cases involving less severe forms of neglect, such as in certain animal hoarding situations, could be useful in addressing the needs of the animals and the individual, without the need for criminal charges.45 In cases with non-cooperative caregivers, a civil mechanism determining an owner’s inability to properly care for animals could require relinquishment of animals and intake into the local shelter.

Study limitations

This study had several limitations. Study data were collected retrospectively with a significant number of case exclusions due to incomplete records. While a systematic approach to case selection and record review was carried out, the quality of case notes input into the software was inconsistent. Human error during case note revision may have occurred.

The study population essentially self-selected to engage with the CE program and therefore primarily consisted of overwhelmed caregivers and cooperative rescuers. These categories of animal hoarders are more willing to accept services and, therefore, may be more likely have a successful outcome with a collaborative approach.15,17 As described in the literature, voluntary engagement programs may be ineffective or inappropriate for managing larger, more severe cases involving rescuers or exploiter hoarders.15,17 These cases often require law enforcement and legal prosecution to achieve successful outcomes.15,17

Additionally, this study was limited to hoarding cases involving cats; the characteristics and outcomes of cases involving other species may vary from these cases.

Finally, the lack of long-term follow-up for some cases with initial successful outcomes leaves the possibility that ultimate outcomes (re-collection or reaching out for services) have not been captured in this study. This limitation may bias findings toward either a higher rate of recidivism or a lower rate or subsequent re-engagement as sufficient time was not provided to assess ultimate outcomes.

Conclusion

Previous research examining animal hoarding interventions and outcomes has largely focused on those involving punitive approaches.19,24 Recently published studies demonstrated that a collaborative approach between both human and animal agencies tailored to individual case factors can produce favorable outcomes for the animals and people involved.15,21

The results from this study demonstrate that programs utilizing a collaborative harm reduction approach can successfully manage animal hoarding cases involving cooperative overwhelmed caregivers and rescuers through spay/neuter and relinquishment. Study findings suggest a need to expand accessible spay/neuter and other collaborative interventions. The results also highlight the value of approaching animal hoarding cases with cooperative caregivers with an interdisciplinary, measured approach to safeguard both human and animal well-being.

Author contributions

Biana Tamimi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration. Emily Dolan: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing – Original Draft. Lisa Kisiel: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft. Elizabeth Berliner: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project Administration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sarah Gray and Emily Patterson-Kane for their help with study design and data curation. We thank Maya Gupta, Elizabeth Brandler, Kevin O’Neill, Randall Lockwood, and Stephanie Janeczko for sharing their expertise in reviewing this document. We also want to thank all of the partner human and animal support agencies that collaborate with the ASPCA to respond to animal hoarding cases in New York City, including the Animal Care Centers of New York, New York State Adult Protective Services, and the New York City Police Department.

References

| 1. | Worth D, Beck AM. Multiple ownership of animals in New York city. Trans Stud Coll Physicians Phila. 1981;3(4): 280–300. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/16154860. Accessed December 22, 2023. |

| 2. | Avery L. From helping to hurting: when acts of ‘good Samaritans’ become felony animal cruelty. Valparaiso Univ Law Rev. 2005;39(4):815–858. https://heinonline.org/HOL/License. Accessed December 22, 2023. |

| 3. | Reinisch AI. Characteristics of six recent animal hoarding cases in Manitoba. Can Vet J. 2009;50:1069–1073. |

| 4. | Sacchettino L, Gatta C, Giuliano VO, et al. Description of twenty-nine animal hoarding cases in Italy: the impact on animal welfare. Animals. 2023;13(18):2968. doi: 10.3390/ani13182968 |

| 5. | Calvo P, Duarte C, Bowen J, Bulbena A, Fatjo J. Characteristics of 24 cases of animal hoarding in Spain. Anim Welfare. 2014;23(2):199–208. doi: 10.7120/09627286.23.2.199 |

| 6. | Joffe M, Shannessy DO, Dhand NK, Westman M, Fawcett A. Characteristics of persons convicted for offences relating to animal hoarding in New South Wales. Aust Vet J. 2014;92(10):369–375. doi: 10.1111/avj.12249 |

| 7. | Ferreira EA, Paloski LH, Costa DB, et al. Animal hoarding disorder: a new psychopathology? Psychiatry Res. 2017;258: 221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.08.030 |

| 8. | da Cunha GR, Martins CM, de Fatima Ceccon-Valente M, et al. Frequency and spatial distributation of animal and object hoarder behavior in Curitiba Paraná State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2017;33(2). doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00001316 |

| 9. | Ockenden E, De Groef B, Marston L. Animal hoarding in Victoria, Australia: an exploratory study. Anthrozoos. 2014;27(1):33–47. doi: 10.2752/175303714X13837396326332 |

| 10. | Elliott R, Snowdon J, Halliday G, Hunt GE, Coleman S. Characteristics of animal hoarding cases referred to the RSPCA in New South Wales, Australia. Aust Vet J. 2019;97(5):149–156. doi: 10.1111/avj.12806 |

| 11. | Dozier ME, Bratiotis C, Broadnax D, Le J, Ayers CR. A description of 17 animal hoarding case files from animal control and a humane society. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.127 |

| 12. | American Psychiatric Association. Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. In: American Psychiatric Association (APA), ed. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 |

| 13. | Arluke A, Patronek G, Lockwood R, Cardona A. Animal hoarding. In: Maher J, Pierpoint H, Beirne P, eds. The Palgrave International Handbook of Animal Abuse Studies. London: Springer Nature; 2017:107–129. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-43183-7 |

| 14. | Ferreira EA, Paloski LH, Costa DB, Moret-Tatay C, Irigaray TQ. Psychopathological comorbid symptoms in animal hoarding disorder. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91(3):853–862. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09743-4 |

| 15. | Patronek G, Loar L, Nathanson J. Animal Hoarding: Structuring Interdisciplinary Responses to Help People, Snimals and Communities at Risk. 2006. www.tufts.edu/vet/cfa/hoarding. Accessed February 22, 2023. |

| 16. | Patronek GJ. Animal hoarding: its roots and recognition. Vet Med. 2006;101(8):520–530. |

| 17. | Lockwood R. Animal hoarding: the challenge for mental health, law enforcement, and animal welfare professionals. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(6):698–716. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2373 |

| 18. | Polak KC, Levy JK, Crawford PC, Leutenegger CM, Moriello KA. Infectious diseases in large-scale cat hoarding investigations. Vet J. 2014;201(2):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.05.020 |

| 19. | Berry C, Patronek G, Lockwood R. Long-term outcomes in animal hoarding cases. Anim Law. 2015;11:11–167. https://heinonline.org/HOL/License. Accessed February 29, 2024. |

| 20. | Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium (HARC). Health implications of animal hoarding. Health Soc Work. 2002;27(2):125–136. doi: 10.1093/hsw/27.2.125 |

| 21. | Strong S, Federico J, Banks R, Williams C. A collaborative model for managing animal hoarding cases. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci. 2019;22(3):267–278. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2018.1490183 |

| 22. | Jacobson LS, Giacinti JA, Robertson J. Medical conditions and outcomes in 371 hoarded cats from 14 sources: a retrospective study (2011–2014). J Feline Med Surg. 2020;22(6):484–491. doi: 10.1177/1098612X19854808 |

| 23. | Stumpf BP, Calacio B, Branca B, Wilnes B. Animal hoarding: a systematic review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2023;45(4):356–365. doi: 10.47626/1516 |

| 24. | Patronek GJ. Hoarding of animals: an under-recognized public health problem in a difficult-to-study population. Public Health Rep. 1999;114:81–87. doi: 10.1093/phr/114.1.81 |

| 25. | Steketee G, Gibson A, Frost RO, Alabiso J, Arluke A, Patronek G. Characteristics and antecedents of people who hoard animals: an exploratory comparative interview study. Rev Gen Psychol. 2011;15(2):114–124. doi: 10.1037/a0023484 |

| 26. | Snowdon J, Halliday G, Elliott R, Hunt GE, Coleman S. Mental health of animal hoarders: a study of consecutive cases in New South Wales. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44(3):480–484. doi: 10.1071/AH19103 |

| 27. | Wilkinson J, Schoultz M, King HM, Neave N, Bailey C. Animal hoarding cases in England: implications for public health services. Front Public Health. 2022;10:899378. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.899378 |

| 28. | Center for Disease Control (CDC), Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. 2024. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/svi/index.html. Accessed December 14, 2023. |

| 29. | Pinillos RG. One Welfare: A Framework to Improve Animal Welfare and Human Well-Being. Wallingford: C.A.B. International; 2018. doi: 10.1079/9781786393845.0000 |

| 30. | García Pinillos R, Appleby MC, Manteca X, Scott-Park F, Smith C, Velarde A. One welfare: a platform for improving human and animal welfare. Vet Record. 2016;179(16):412–413. doi: 10.1136/vr.i5470 |

| 31. | Cahill A, Cusick A, Englebright L. Assembly Bill A261. 2019. https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2019/A261. Accessed February 19, 2024. |

| 32. | Hawk M, Coulter RWS, Egan JE, et al. Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):70. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0196-4 |

| 33. | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Harm Reduction Framework. 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/harm-reduction/. Accessed March 24, 2024. |

| 34. | World Organization for Animal Health. Animal Welfare: The Five Freedoms. Animal Welfare at WOAH; 2024. https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-welfare/. Accessed February 19, 2024. |

| 35. | Frost RO, Patronek G, Rosenfield E. Comparison of object and animal hoarding. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:885–891. doi: 10.1002/da.20826 |

| 36. | Human Animal Support Services. The HASS Playbook. 2024. https://www.humananimalsupportservices.org/hass-playbook/. Accessed December 22, 2023. |

| 37. | Arkow P. Human–animal relationships and social work: opportunities beyond the veterinary environment. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2020;37(6):573–588. doi: 10.1007/s10560-020-00697-x |

| 38. | Hoy-Gerlach J, Ojha M, Arkow P. Social workers in animal shelters: a strategy toward reducing occupational stress among animal shelter workers. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.734396 |

| 39. | Access to Veterinary Care Coalition. Access to Veterinary Care: Barriers, Current Practices, and Public Policy. 2018. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_smalpubs/17. Accessed November 28, 2023. |

| 40. | Neal SM, Greenberg MJ. Putting access to veterinary care on the map: a veterinary care accessibility index. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:857644. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.857644 |

| 41. | Bunke L, Harrison S, Angliss G, Hanselmann R. Establishing a working definition for veterinary care desert. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;262:1–8. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.06.0331 |

| 42. | Newbury S, Hurley K. Population management. In: Miller L, Zawistowski S, eds. Shelter Medicine for Veterinarians and Staff. 2nd ed. Ames: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013:93–113. |

| 43. | The Association of Shelter Veterinarians. The Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2022. doi: 10.56771/ASVguidelines.2022 |

| 44. | Brown SE. Theoretical concepts from self psychology applied to animal hoarding. Soc Anim. 2011;19(2):175–193. doi: 10.1163/156853011X563006 |

| 45. | Sen. Gianaris. Senate Bill S8543. 2024. https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2023/S8543. Accessed March 2, 2024. |