ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

When You Cannot Put That Cat Back Where It Came From – The Call for a ‘Working Cat Program’ Implementation

Simone Guerios1*, Katie Houston1, Michaela Oglesby1, Megan Farinha2 and Melissa Jenkins2

1Department of Small Animal Clinical Science, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida;

2Operation Catnip, Gainesville, FL

Abstract

Introduction: Operation Catnip’s (OC) Working Cat Program (WCP) was created to contribute to life-saving efforts for poorly socialized unowned cats that cannot return to their original location and in turn relocation needs to be implemented. The goal of this study was to evaluate the OC’s WCP, a cat management program, conducted in Florida from January 1, 2019, to December 1, 2023.

Methods: Data from cats enrolled in the OC’s WCP were retrieved from electronic records and analyzed using descriptive statistics. Cat adopters were surveyed to assess satisfaction with their adoptions and to evaluate the broader outcomes of the program.

Results: A total of 968 cats were enrolled in 5 years of the program. In total, 99% (n = 959) of the cats had a live release rate (959), where 90% (862) were ‘hired’ (adopted into non-traditional homes), 9.9% (95) were transferred to rescue groups (to be adopted into traditional homes), and 2 were returned to their original location (return to field). 85% of the adopters who responded to a post-adoption survey (329/387) were very or completely satisfied with their adopted cat’s performance, and only 10% (40/387) were not or were somewhat satisfied with their adopted cat’s performance.

Conclusion: Implementing cat management programs like OC’s WCP is a viable and successful way to provide positive live outcomes to cats unsuitable for traditional adoption, as an alternative to euthanasia.

Keywords: pet overpopulation; shelter medicine; cat relinquishment; euthanasia; feral cats; community cats; fearful cats

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2024, 3: 89 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v3.89

Copyright: © 2024 Simone Guerios et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 14 April 2024; Revised: 19 June 2024; Accepted: 21 August 2024

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. This research received no funding.

Correspondence: *Simone Guerios, Department of Small Animal Clinical Science, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida. Email: sdguerios@ufl.edu

Reviewers: Hayley Hadden, Emma Vitello

Historically, shelters have faced the challenge of finding solutions to reduce the euthanasia of cats in good general health that are poorly socialized. Over the past four decades, robust high-impact Trap-Neuter-Vaccinate-Return (TNVR) programs and more recent return-to-field (RTF) programs have been utilized as a successful strategy for managing the unowned, free-roaming cat population.1,2 RTF and TNVR programs operate at a similar capacity, where community cats are trapped, transported to a shelter or low-cost clinic, sterilized, vaccinated, ear-tipped, and returned to the location where they were trapped. The main difference is that RTF programs are shelter-based and TNVR programs are community-based. With RTF programs, cats are admitted to shelters as ‘strays’ through animal control field services or public relinquishment. Through strategic pathway planning and shelter staff behavior assessments, cats are designated as RTF. On the other hand, there is no admission into TNVR programs; caregivers are the primary point of contact and are required to release their trapped cats and be available to monitor and care for the cats after release.3 These combined programs appear to reduce the intake and euthanasia of unowned, free-roaming community cats in shelters.4,5

Operation Catnip (OC) is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization dedicated to saving the lives of community cats in Alachua, Bradford, Gilchrist, Levy, Columbia, Putnam, and Union County – Florida. Since its beginning in 1998, the organization has helped to sterilize more than 86,000 community cats. In 2023, OC sterilized 7,961 cats through TNVR and RTF programs.6 While their TNVR program is the organization’s primary focus, OC plays a central role in contributing to life-saving efforts for poorly socialized unowned cats that cannot be returned to their original outdoor homes through their Working Cat Program (WCP). OC established the WCP in 2016 as a pilot program. From August 2016 to December 2017, WCP placed more than 90 cats in non-traditional homes. In January 2018, as a result of the success of the first year, the program expanded and added a covered outdoor multi-housing shelter (Catio) to safely house working cat candidates. The Catio provides a less stressful environment for cats awaiting veterinary care and adoption placement. It reduces human interaction, allowing for more accurate behavioral observations and assessments because of the nature of being housed in a less stressful, outdoor environment. As OC’s WCP has continued to grow throughout the years, OC has additionally provided mentorship to other organizations interested in piloting their WCPs.

Program overview

OC’s WCP goal is to work in partnership with municipal shelters and local rescue groups to place poorly socialized cats in non-traditional homes as working cats. Non-traditional homes include but are not limited to barns, farms, businesses, breweries, airport hangars, feed stores, golf courses, and other businesses. The program emphasizes placement for cats that need relocation from overwhelmed colony sites or are at high risk for euthanasia in shelters.

Most of the cats selected for the program are feral or unsocialized cats that have lived outdoors and have experienced its dangers (i.e. traffic and wild predators) or come from overwhelmed and unmanaged colonies/hoarding cases. These are cats that cannot return to their original location and generally cannot be adopted as companion animals because of their behavior. They normally have little interest in bonding with humans and prefer the company of other cats. Additionally, a working cat also can encompass a variety of other cat populations that may not be suitable for traditional indoor-only adoption. For example, cats with inappropriate elimination disorders have historically struggled to find adopters willing to endure the constant cleaning of urine and feces in a home. Still, they would thrive in an outdoor/indoor or outdoor-only setting. Even cats that display deteriorating behavior and well-being in a shelter can potentially be good candidates for a WCP. These cats can tolerate handling and may become friendly after some time with socialization efforts and/or a change of environment. Having a WCP as an additional live outcome pathway option allows shelter organizations to assess their financial and staffing resources and make proactive and timely decisions for each cat.

Historically, adopters for this program have been individuals looking for reliable pest control options on their property (barn cats). WCP adopters also include individuals who like cats but cannot keep them indoors because of medical issues or personal preferences. Adopters usually live on large multi-acre properties. However, adopters living in residential neighborhoods are not disqualified from adoption. They are warned that cats may interact with other people, who may feed them or consider them a nuisance. Ultimately, WCP can connect potential adopters to cats with low affection expectations. The low-stress environment of a non-traditional home allows these cats to thrive, connect, and bond with people on their terms.

Adopters must agree to acclimate the cats for 2–4 weeks in a small, organized space, such as a large dog crate, work, or tack room, before releasing them. Working cats should be fed commercially prepared cat food daily, even after release. Providing daily meals reduces the chances of cats abandoning the property to search for other food sources. Most adopters are encouraged to adopt the cats in pairs, with few exceptions. Exceptions may be made for friendly cats or adopters with established resident cats that will welcome a new cat. The WCP coordinator is responsible for selecting the cats for the adopters, with the cats that have been in the program the longest being the first ones to be sent for adoption. Known groups of cats are kept together to preserve their well-being and the bond created among them. If adopters express interest in a particular cat or any cat, the program director can consider their request and honor it at their discretion.

Admission process and adaptation

There are two main routes of admission to the program. The first is through direct communication between the shelter and the OC, where the shelter requests the transfer to the WCP because the cat is unsuitable for traditional adoption or cannot be returned to their previous location. The program coordinator evaluates the medical and behavioral history provided by the shelter to assess whether transfer is appropriate. The second category of intake is ‘shelter diversion’, which includes cats that do not come directly from a shelter or a rescue. These intakes are similar to owner surrender, where a caregiver can no longer provide care for the cat and contact WCP directly instead of the local shelter. Other cases that are included in this category are cats that live in heavily overpopulated conditions, without adequate resources to maintain quality of life. Caregivers in these locations are often unable to support the number of cats they have, even with OC’s efforts to maintain the TNVR program in the area to eliminate the opportunity for population growth. In these cases, it is decided by OC’s outreach coordinator to relocate some of the cats to reduce the burden on their caregivers and to provide a better quality of life for both remaining and relocated cats.

All cats enrolled in the WCP are sterilized, vaccinated for rabies and Feline Viral Rhinotracheitis, Calicivirus, and Panleukopenia vaccine (FVRCP), dewormed, given flea prevention, microchipped, and tested for FeLV/FIV. After all medical issues are addressed, cats are then released into the Catio, a covered outdoor shelter that provides a confined, safe, and quiet environment for adaptation and behavior observation of the cats enrolled in the program. The OC Catio is 11 feet wide and 14.7 inches long and includes multiple levels of shelving, various climbing structures, and several hiding spaces. Daily, OC staff and volunteers care for and observe the cats and report to the program director if there are concerns about a particular cat’s ability to get along with other cats, notable changes in behavior and adaptation, and/or medical concerns.

Cats who consistently show friendly behavior, readily solicit attention from multiple individuals, and are tolerant of petting, handling, and holding, thus appearing to be adaptable to a traditional home, are removed from the program and transferred to a rescue partner. However, most cats entering the WCP look for a hiding place immediately after being released and are most comfortable when left alone by humans.

Outlined project’s goals

The goal of this article is to report the outcome of the WCP, a cat management program conducted over 5 years at OC in Florida. It is anticipated that the implementation of innovative strategies to manage the poorly socialized cat population that needs to be relocated and is not suitable for traditional adoption can serve as a guide for shelters and rescues to improve the live outcomes of cats admitted to these institutions.

Methods

This study was conducted at OC (Gainesville, FL), including data from cats enrolled in the OC’s WCP. Data were collected from January 1, 2019, to December 1, 2023, and retrieved from electronic records (Clinic HQ software and Shelterluv software), and a post-adoption survey response. Before admission to the WCP, the health condition of each cat was assessed and properly addressed. A standardized intake protocol was followed for all cats. Additional diagnosis and treatment provided before admission, e.g. radiography, cytology, and surgical interventions such as castration, limb amputation, and enucleation, were included in each patient’s medical record. Cats with diseases that impact quality of life were excluded from the program. Intake criteria also require a FeLV/FIV combo test performed by the rescue or shelter before enrolling the cat in the program. The test was not repeated after enrollment.

During admission and adoption, an OC staff was responsible for categorizing the cats into a behavioral group (friendly, fearful, or feral). During their time in the program, a staff or volunteer was responsible for observing changes in behavior. Cats were grouped into different categories based on subjective behavior observation. Feral cats displayed aggressive behavior such as hissing, scratching, growling, and attempting to bite. They also tended to hide during the day and had a history of living outdoors. Fearful cats exhibited similar behavior to feral cats but were more tolerant of people, especially after spending some time in the shelter. They often had a history of being community cats or living indoors. On the other hand, friendly cats were comfortable with petting, handling, and being held. Behavioral observations were recorded in medical records. There was no required monitoring time following release into the Catio.

Data were categorized for the following variables: origin (shelter/rescue/shelter diversion program), sex (male vs female), FeLV/FIV status (positive vs negative), behavior assessment on intake and at adoption (feral vs fearful vs friendly vs not assessed), the outcome from the program (adopted as a working cat vs transferred to another organization vs RTF vs lost vs dead/euthanized), and the length of stay. Length of stay consisted of the total number of days a cat spent in the WCP at OC.

To assess satisfaction with the adoption and to evaluate the outcome of the program, a brief post-adoption survey was conducted via cell phone text messages by an OC staff member to all cat adopters in the program during the study period.

The text message read, ‘Hi! I am with Operation Catnip, and we are gathering some data from our working cat program from ____ (year). I saw you guys adopted ____(cat(s) name(s)). I was wondering if you had a minute to fill out some information about them.

1) How many weeks did it take for the cat(s) to acclimate?

2) Is the cat(s) still on the property? Yes, No, Does not Know

3) Is the cat(s) getting along with other cats on the property? Yes, No, Not interacting, Does not Know

4) Is the cat(s) doing a good job at controlling pests? Yes, No, Does not Know

5) Has the cat(s) behavior changed from feral to friendly? Yes, No, Does not Know

6) How satisfied are you with the cat(s) performance on a scale of 1 (not at all satisfied), 2 (somewhat satisfied), 3 (moderately satisfied), 4 (very satisfied), and 5 (completely satisfied)? Thank you so much for your time’.

Each adopter was contacted only once during the study and at least 30 days after adoption. The time interval between the adoption and sending of survey messages varied among the years of study. For each year, all responses and the time after adoption that adopters were surveyed were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet. No identifiable client or patient information was stored with the data available for the study.

A series of descriptive statistics were used to assess the data and results are explored descriptively. Descriptive statistics consisted of the mean ± SD (standard deviation) and the count percentage (%) used to report the frequency of the data.

Results

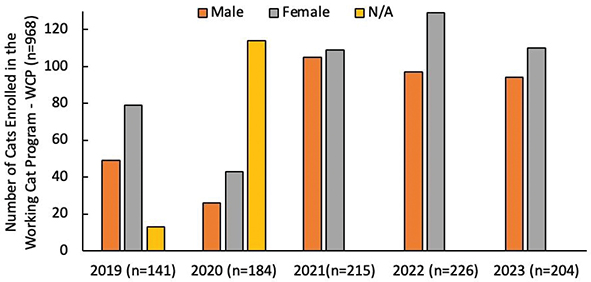

A total of 968 cats were enrolled in the OC’s WCP from January 2019 to November 2023. Of these, 470 were female, 371 were male, and 127 were unassessed cats (Figure 1). Within the cats, 33 were positive for FIV and 1 for FeLV, 19 had enucleation surgery, 2 had surgical correction for entropion, 9 had hindlimb or forelimb amputation, and 1 was diagnosed with urinary incontinence.

Fig. 1. Number of cats enrolled in the WCP and sex distribution per year of study. WCP: Working Cat Program.

Forty-six percent (n = 445) of the intake was from the OC intake diversion program, 30% (n = 293) were transferred from rescue partners, and 24% (n = 230) were transferred from municipal shelters (Table 1). The mean length of stay for the cats enrolled in the WCP was 22.27 days (SD ± 21.07), with a range of 1–143 days at the program.

In total, 99% (n = 959) of the cats had a live release rare, where 90% (n = 862) were hired (adopted into non-traditional homes), 9.9% (n = 95) were transferred to a rescue group (to be adopted into traditional homes), and 2 were returned to their original place (RTF) (Table 1). Negative outcome (1%, n = 11) reasons included 2 cats that were euthanized because of severe pododermatitis, 5 escaped from the Catio, and 2 were found dead. A necropsy was performed on one of the deceased cats and the cause of death was associated with heartworm disease. Of the hired cats, 5 (0.6%) were returned to WCP.

Of the 968 cats that entered the program, 56% (n = 539) were classified as feral on intake, 33% fearful (n = 321), and 11% friendly (n = 108). Outcome behavioral assessment, before adoption or transfer to a rescue, was not performed in 2019, excluding 141 cats from this analysis. For the subsequent years, a total of 291 cats had their behavioral assessment recorded. Of these, 74% were classified as friendly (n = 216), 22% feral (n = 65), and 4% fearful (n = 10).

In the post-adoption survey, in 2019 and 2020, adopters were contacted 35 days after adoption. For subsequent years from 2021 to 2023, adopters were contacted within a minimum of 140 days and a maximum of 763 days after adoption. The response rate was 45% (387/862).

The mean acclimation time on the property was 21 days (SD ± 7.85) with a minimum of 0 days and a maximum of 56 days. Of the 387 adopters who responded to the survey, 81% (n = 314) stated that the cat was still on the property, 18% (n = 70) said the cat was no longer on the property, and 1% (n = 3) did not know. For cats adopted in 2021, 2022, and 2023, the mean length of stay on the property was 324.66 days (SD ± 31.44, with a minimum of 14 days and a maximum of 763 days).

The question about the cats’ interactions with other cats on the property generated a positive response in 70% (271/387) of those responders. A negative response was obtained from 15.8% (n = 61). Of these, 12.4% (n = 48) reported that the cat was not interacting with other cats and 3.4% (n = 13) said the cat was not getting along with other cats on the property. Fifty-five responders did not know if the cat was interacting with other cats. When questioned about pest control, 72% (n = 282) of responders reported yes, 7.8% (n = 30) no, and 19.4% (n = 75) did not know. When questioned about behavior changing after adoption, 64% (n = 294) reported the behavior change from feral to friendly, 19.6% (n = 76) stated the cat was still feral and/or fearful, and 16% (n = 62) did not know.

The question regarding satisfaction with the cat’s performance was represented on a scale of 1–5, with 1 being ‘not at all satisfied’, 2 being ‘somewhat satisfied’, 3 being ‘moderately satisfied’, 4 being ‘very satisfied’, and 5 being ‘completely satisfied’. Overall, 85% (n = 329) of all respondents were very or completely satisfied with the cat’s performance, 5% (n = 18) were moderately satisfied, and 10% (n = 40) were not or were somewhat satisfied (Table 2).

Discussion

This study describes the outcomes obtained over a 5-year cat management program conducted in Central Florida. During the study period, 968 cats were managed as part of the program, and of these, 90% had a live release rate (LRR), supporting the hypothesis that the WCP is a successful alternative for managing poorly socialized cats that cannot be returned to their previous indoor or outdoor home and are not suitable for traditional adoption.

Approximately half of the intake came from municipal shelters and rescues. The partnership between OC’s WCP and shelters has helped to reduce the length of stay of cats and the number of cats euthanized because of behavior. Unsocialized cats are among the most frequent reasons for owner surrender or return after adoption because of their behavior and are particularly at risk for euthanasia in animal shelters because of lower appeal for adoption.2 Management programs that prevent animals from entering shelters, combined with measures that address population control such as TNVR and RTF programs have a fundamental role in helping to reduce overcrowding in shelters.2,7 OC’s shelter diversion program is a cat management program that has the goal of reducing the number of cats entering the shelter system. In this study, 45% of intake came from the shelter diversion program. OC’s shelter diversion program grew significantly in the early years of the WCP when compared to subsequent years. In 2019, approximately 1/3 of the cat (n = 32) intake was from the shelter diversion program and 2/3 (n = 109) from rescues/shelters. In the following years, about half of the intake was from the shelter diversion program. Keeping animals out of the shelter is a strategic way of dealing with the animal crisis observed in the United States. In 2023, shelters showed an 8% increase in the number of dogs and cats admitted, a reduction in the number of adoptions, and, consequently, an increase in the euthanasia rate compared to 2022.8,9 Additional research is needed to conclude if the WCP increased the LRR for municipal shelters and rescues. Although this study did not have the data to make that conclusion, we would posit that because a WCP is an additional live outcome pathway and decreased length of stay for cats, we would expect to see an increase in LRR.

Before intake in OC’s WCP, all cats were screened for FIV/FeLV. During the study period, 33 cats were positive for FIV and 1 for FeLV. Retroviral testing is recommended for group-housed cats and not recommended for routine TNR and RTF programs.10 WCP is a combination of group housing and TNR relocation, so it was decided to perform retrovirus testing before admission. FIV-positive cats in good health were accepted into the program without concern, as they were expected to live a normal lifespan, and transmission of FIV to uninfected cats is minimal after castration.11 The only FeLV-positive cat accepted to the program was transferred to a rescue group 1 day after admission. This decision was based on the fact that FeLV is more transmissible between cats with prolonged close contact, similar to the group housing used in the WCP. However, future FeLV-positive cats will be considered for inclusion in the program, as castration reduces virus transmission that occurs from queen to kittens,12 and most cats tend to hide when released into the Catio and tend not to interact with each other because of their fearful behavior.

The length of stay for cats enrolled in the WCP varied greatly from 1 day to 143 days. The longer length of stay was related to medical issues, mainly because these cats were not available for adoption at the time of admission as they needed medical treatment and/or monitoring. Furthermore, elderly cats or those that have undergone treatments (e.g. limb amputations or enucleations) were considered less adoptable by adopters. Although adopters cannot choose the cat they adopt, they have the option to choose whether they are open to cats with ‘special needs’. While the priority is to reduce the length of stay in the program by placing cats in homes based on intake day, cats with special needs await adopters who are open to adopting them, which often increases the length of stay in the program. This finding is similar to previous studies, which consistently report that older cats (>7 years) and those with a history of previous or current disease are less adoptable, have longer lengths of stay in shelters, and are at higher risk of being returned after adoption.13–16

On intake, more cats were categorized as having feral or fearful behavior compared to the outcome. The same pattern was observed after adoption as a working cat. This can be explained by the presence of high levels of stress because of the cats being in an unfamiliar environment and/or around unfamiliar people during intake or the first few weeks after adoption. The stress levels in fearful cats decrease over time, especially in cases where socialization levels have been reduced or are non-existent.17 Standardized behavior recording methods designed to accurately monitor changes in behavior over time and objective behavior observation performed by the same observer throughout the time the cat remained in the program would help to determine behavioral changes and categorization more accurately.

Despite exhibiting antisocial behavior initially, in the post-adoption survey, it was reported that most cats displayed social behavior, interacting with other cats that previously inhabited the area and spending time in proximity. Human activities including sterilization, food supply, and a good level of care are important factors that influence the reduction of aggressive behavior among free-ranging cats, allowing successful relocation.18 The relocation of unwanted undersocialized cats, cats that are not suitable to be returned to their original location or are not suitable for traditional adoption, is part of population management strategies supported by the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP).2 However, relocation needs to be carefully considered as a population management tool because of the territorial nature of cats. The results of this study showed successful relocations of the cats adopted from the WCP.

The human–animal bond between caregivers and free-roaming cats, regardless of the level of sociability, was recently established and showed that the fact that community cats are unowned did not reduce the strength of this bond.19 Although cats adopted through OC’s WCP are considered owned, these cats are expected to live outdoors in the community, similar to those who have participated in TNVR or RTF programs. The bond between caregivers and adopted cats could be perceived by the overall satisfaction of their working cat’s performance. The majority of the adopters (85%) were very or completely satisfied with their cat, regardless of the level of sociability.

This research included some further limitations. The limited number of survey respondents and the difference in time between questionnaire distribution and adoption limited comparisons among years. The program advocates a 2-week acclimatization period in a large dog crate or tack room to familiarize cats with caregivers. The present study did not evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this confinement. Future studies are necessary to assess the impact of the acclimatization period on the cats’ behavior and to determine if this period should be implemented before releasing the cats onto the property. Another fundamental limitation is response bias. It is possible that individuals who feel strongly positive about community cats were more likely to respond to the survey. An additional limitation includes the survey duration. The number of questions and possible answers were selected to keep the survey short and easy to complete. This may have limited our ability to obtain a complete picture of the cats’ behavior and performance after adoption and adopters’ satisfaction.

The present study did not evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this acclimatization period. Future studies are needed to address the impact that this acclimatization time has on the cats’ behavior, and the need for confinement before releasing them onto the property.

Conclusion

In conclusion, WCPs are an alternative for managing poorly socialized cats based on an understanding of cat behavior and population dynamics. Although there are disadvantages to relocating cats, the results from our study suggest that WCPs are well suited for well-managed relocations, making instrumental changes that improve cat welfare, and achieving overall caregiver satisfaction. These findings create a solid basis for suggesting the implementation of more well-structured WCPs should be considered a mainstay in animal welfare throughout Florida (and nationwide) in terms of promoting live-saving capacity and finding the right outcome for every cat.

Authors’ contributions

SG: formal analysis, writing (original, draft, and review); MJ: conceptualization, supervision, project administration, writing (draft and review); MF: survey development, data collection; MO: conceptualization, survey development; KH: data collection and writing. The manuscript was initially written by SG and MJ, with subsequent versions of the manuscript edited and approved by all authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the cat adopters of the WCP who participated in the survey.

Statement of ethics

This research received an exempt determination from the University of Florida (ET00022582). This work involved the use of non-experimental animals (including data from prospective or retrospective studies). Established, internationally recognized high standards (‘best practice’) of individual veterinary clinical patient care were followed.

References

| 1. | Boone JD, Miller PS, Briggs JR, et al. A long-term lens: cumulative impacts of free-roaming cat management strategy and intensity on preventable cat mortalities. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:238. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00238 |

| 2. | Halls V, Bessant C. Managing cat populations based on an understanding of cat lifestyle and population dynamics. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2023;2(S2). doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.58 |

| 3. | Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. Back to school: an updated evaluation of the effectiveness of a long-term trap-neuter-return program on a university’s free-roaming cat population. Anim Open Access J MDPI. 2019;9(10):768. doi: 10.3390/ani9100768 |

| 4. | Levy JK, Isaza NM, Scott KC. Effect of high-impact targeted trap-neuter-return and adoption of community cats on cat intake to a shelter. Vet J Lond Engl 1997. 2014;201(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.05.001 |

| 5. | Zito S, Aguilar G, Vigeant S, Dale A. Assessment of a targeted trap-neuter-return pilot study in Auckland, New Zealand. Anim Open Access J MDPI. 2018;8(5):73. doi: 10.3390/ani8050073 |

| 6. | Operation Catnip of Gainesville Inc – GuideStar Profile. https://www.guidestar.org/profile/59-3522372. Accessed November 27, 2023. |

| 7. | Boone JD. Better trap-neuter-return for free-roaming cats: using models and monitoring to improve population management. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17(9):800–807. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15594995 |

| 8. | SAC. Intake and outcome data analysis, Q3 2023. Shelter Animals Count. https://www.shelteranimalscount.org/intake-and-outcome-data-analysis-q3-2023/. Accessed November 27, 2023. |

| 9. | hills-pet-nutrition-2023-state-of-shelter-adoption-report.pdf. https://www.hillspet.com/content/dam/cp-sites/hills/hills-pet/en_us/general/documents/shelter/hills-pet-nutrition-2023-state-of-shelter-adoption-report.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2023. |

| 10. | Little S, Levy J, Hartmann K, et al. 2020 AAFP Feline retrovirus testing and management guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2020;22(1):5–30. doi: 10.1177/1098612X19895940 |

| 11. | Litster AL. Transmission of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) among cohabiting cats in two cat rescue shelters. Vet J Lond Engl 1997. 2014;201(2):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.02.030 |

| 12. | Dezubiria P, Amirian ES, Spera K, Crawford PC, Levy JK. Animal shelter management of feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus infections in cats. Front Vet Sci. 2023;9:1003388. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.1003388 |

| 13. | Rix C, Westman M, Allum L, et al. The effect of name and narrative voice in online adoption profiles on the length of stay of sheltered cats in the UK. Animals. 2021;11(1):62. doi: 10.3390/ani11010062 |

| 14. | Brown WP, Stephan VL. The influence of the degree of socialization and age on the length of stay of shelter cats. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2021;24(3):238–245. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2020.1733574 |

| 15. | Mundschau V, Suchak M. When and why cats are returned to shelters. Anim Open Access J MDPI. 2023;13(2):243. doi: 10.3390/ani13020243 |

| 16. | Hawes SM, Kerrigan JM, Hupe T, Morris KN. Factors informing the return of adopted dogs and cats to an animal shelter. Anim Open Access J MDPI. 2020;10(9):1573. doi: 10.3390/ani10091573 |

| 17. | Jacobson LS, Ellis JJ, Janke KJ, Giacinti JA, Robertson JV. Behavior and adaptability of hoarded cats admitted to an animal shelter. J Feline Med Surg. 2022;24(8):e232–e243. doi: 10.1177/1098612X221102122 |

| 18. | Vitale KR. The social lives of free-ranging cats. Animals. 2022;12(1):126. doi: 10.3390/ani12010126 |

| 19. | Neal SM, Wolf PJ. A cat is a cat: attachment to community cats transcends ownership status. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2023;2(1). doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.62 |