PRINCIPLES OF VETERINARY COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Brittany Watson, MS, VMD, PhD, DACVPM

Director of Shelter Medicine and Community Engagement

Associate Professor in Shelter Medicine and Community Engagement, Clinician Educator (CE)

Department of Clinical Sciences & Advanced Medicine

University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Elizabeth Berliner, DVM, MA, DABVP

(Shelter Medicine Practice, Canine & Feline Practice)

Senior Director, Shelter Medicine Services, ASPCA

Courtesy Associate Clinical Professor

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine Ithaca, NY

Lena DeTar, DVM, MS, DACVPM, DABVP

(Shelter Medicine Practice)

Maddie’s® Shelter Medicine Program

Associate Clinical Professor

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine Ithaca, NY

Emily McCobb, DVM, MS, DACVAA

Associate Clinical Professor of Anesthesiology and Community Medicine

Center for Animals and Public Policy and Department of Clinical Sciences

Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

Tufts University

North Grafton, MA

William Frahm-Gilles, DVM

Access Veterinary Care

Minneapolis, MN

Erin Henry, VMD, DACVPM

Assistant Clinical Professor

Maddie’s® Shelter Medicine Program

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine Ithaca, NY

Erin King, MS

Civic Life Coordinator

Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life PhD Candidate

Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

Tufts University

North Grafton, MA

Lauren Powell, PhD

Lecturer in Animal Welfare and Behavior

Department of Clinical Sciences & Advanced Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

Philadelphia, PA

Chelsea Reinhard, DVM, MPH, DACVPM, DABVP

(Shelter Medicine Practice)

Bernice Barbour Assistant Professor of Clinical Shelter Medicine

Department of Clinical Sciences & Advanced Medicine

University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia, PA

Jenny Stavisky, MRCVS, BVMS, PhD, PGCHE FHEA

Clinical Research Manager

Vetpartners, UK

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2024 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/VCEprinciples.2024

Copyright: © 2024 Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Published: 12 September 2024

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Peter Javian for assistance with the logistics and compilation of this document. We would also like to thank Kirsten White, who helped compile the glossary, and Karen Verderame for assistance with distribution. Both of these individuals contributed greatly to conversations regarding the formal feedback process and were key members of the development team. Padraig McCobb designed our graphical abstract.

The authors acknowledge the following individuals who provided edits and suggestions to the document. This document was significantly enhanced by their insights and assistance, and they were a critical part of the development process. This list only includes those individuals who elected to be recognized. There were many other individuals who are not identified here also contributed meaningful and helpful feedback to the authorship team.

Companions and Animals for Reform and Equity (also known as CARE)

National BIPOC Led Human and Animal Well-being Organization

https://careawo.org

Chumkee Aziz, DVM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice)

University of California- Davis, Koret Shelter Medicine Program

Maya Gupta, PhD

Senior Director, Research

ASPCA

Lynn Henderson, DVM, MEd, CHPV

Veterinary Director, Kim & Stu Lang Community Healthcare Partnership Program

Ontario Veterinary College

Kristin Jankowski, VMD

Access to Care Veterinarian, UC Davis One Health Institute

Advisor, Knights Landing One Health Clinic, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, Director of Veterinary Services, Open Door Veterinary Collective

Ronald J. Orchard, DVM, MPH, CAWA

Clinical Instructor of Community Outreach

College of Veterinary Medicine

Kansas State University

Karen Ward, DVM

Chief Veterinary Officer

Toronto Humane Society

Jennifer Weisent, DVM, PhD

Associate Clinical Professor, Shelter Medicine

University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine

Windi Wojdak, RVT and Aleisha Swartz, DVM

Rural Area Veterinary Services

Humane Society of the United States

Executive summary

The concepts of One Health and One Welfare recognize the integral and complex relationship between animals, the environment, and human health. Pivotal events such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) global pandemic and Hurricane Katrina have highlighted how integral animals are to families and communities; even in times of crisis, people rally to protect and care for their animals despite risks to their own well-being. Health inequities and social determinants of health are increasingly being recognized in the veterinary landscape, which has inspired many groups to initiate projects that support community members and their pets.

When engaging with the animals of marginalized, underserved, or underrepresented communities, the veterinary medical field has opportunities and responsibilities. Project volunteers are often excited and passionate, and if guided well, their efforts can have significant impacts on people and their animals. Unfortunately, good intentions do not guarantee positive outcomes. Our field has an obligation to identify and follow evidence-based ethical engagement practices refined through decades of research from human health engagement programs. As veterinary community engagement continues to gain momentum in academic and research settings, the public sector, philanthropic organizations, and veterinary student training programs, formal guidelines for such engagement have become necessary.

These Principles of Veterinary Community Engagement are closely adapted from the second edition of the Principles of Community Engagement, published in 2011 by a coalition of human health agencies to guide human healthcare programs. Our publication echoes their original principles and reflects their chapter titles and concepts but has been reorganized and refined to focus on programs providing healthcare services to animals.

Many types of animal-related engagement occur in communities. The scope of this resource is focused on programs providing animal health services in a community partnership, especially those involving veterinary care. The concepts described here may widely apply to other animal areas such as educational public and classroom outreach, animal-assisted healthcare, and human-animal interactions with service and therapy animals; however, these programs are not the primary focus of this document.

The intended audience for this document includes individuals designing, leading, and participating in veterinary community engagement programs. Interested parties include instructors, veterinary practitioners, academic institutions, governmental agencies, non-governmental organizations, community members, students, and field leaders who collaboratively help to ensure organizers are following best practices in public health and community engagement and minimizing harm to animal and human populations (see Chapter 1).

As program leaders and representatives read this document, they are likely to identify deficits in their programming. This process can be uncomfortable but represents an opportunity for growth and development. Most programs will not manage to fully meet all nine principles. As with medical error reporting and clinical operations improvement in hospital settings, identifying and openly discussing areas for improvement is essential for accountability and progress.

This document was developed collaboratively by a group of veterinarians and researchers from multiple institutions. The original concept was developed at a retreat funded by the Arnall Family Foundation for the Northeast Consortium of Shelter and Community Medicine in 2022. Draft principles were discussed at an open round table at the 2022 Access to Veterinary Care Conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The proposed document was then sent to veterinary community engagement experts for comments and review; we deeply appreciate their insight and suggestions. Feedback was discussed and integrated at a follow-up retreat in 2023, also funded by the Arnall Family Foundation. The goal of this document is to enhance understanding of the challenges in designing, implementing, and sustaining veterinary engagement programs and to ensure the dignity, health and welfare of animals and the communities caring for them.

Three appendixes are also included in this document: a glossary of terms (Appendix A), a one-page list of the nine principles (Appendix B), and profiles of veterinary engagement programs (Appendix C). Initiatives selected for inclusion in the program profiles are provided as case examples of individual principles in the document. We are grateful to those who spent time filling out surveys or interviewing with the team about their efforts. Inclusion in this document does not constitute an endorsement of a program. Rather, inclusion is intended to illustrate via example in a different, potentially accessible, way consideration or the use of the principles of veterinary community engagement in a real-life setting.

Finally, a note on language: terminology and concepts change with time, sometimes rapidly. In particular, language describing community relationships and identity are in flux as the world tackles urgent issues in social justice and widespread inequity. We anticipate knowledge and insights will evolve in the field and future findings may contradict parts of what we publish at this time point. We also recognize that terminology cited from the literature may have problematic origins without equivalent replacement terms. As an example, we have used the term ‘interested parties’ throughout this document as a replacement for ‘stakeholders’ due to the covetous connotation of this term, except when citing directly from the primary literature. The language that we use on a daily basis is important and with intention, we can begin to realign historic power imbalances. We ask that our language be taken in the spirit and context that it is intended; these guidelines are presented as a living document and revision will be required.

Chapter 1: Veterinary community engagement: organizing concepts and definitions

Key objective: This chapter provides an abbreviated overview of relevant community engagement definitions and concepts with an emphasis on important and applicable concepts specific to programs that provide animal health services.

Defining community engagement

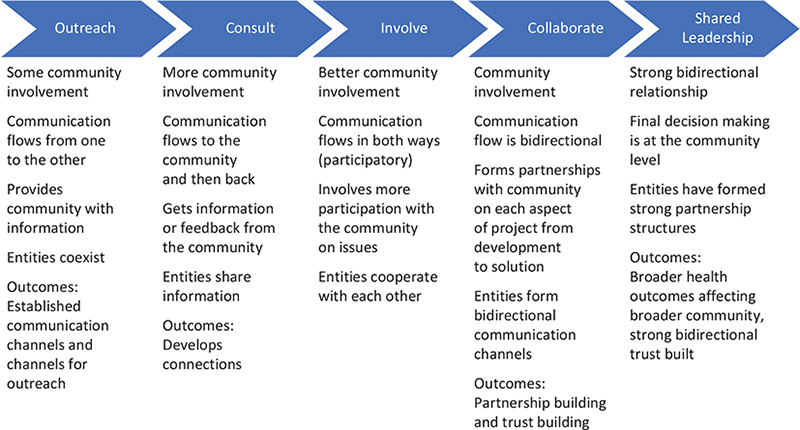

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Principles of Community Engagement (PCE), which inspired this document, defines community engagement as the process of working collaboratively with groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting their well-being. Community engagement is a powerful vehicle for bringing about changes that improve the health of the community and its members.1 In this spirit, we define veterinary community engagement (VCE) as the process of working in collaboration with communities to provide veterinary medical services that impact the health and well-being of animals and humans who care for them. Engagement can take many forms and have different magnitudes (see Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1. Continuum of community engagement-increasing level of community involvement, impact, trust, and communication flow. Reproduced from CDC.2

Community can be defined in many ways, with relationships representing shared geographic, value-based, and cultural systems while still providing for individual differences. The PCE describes four ‘concepts of community’ which inform community engagement: systems, social, virtual, and individual perspectives.2 These concepts also apply to the process of VCE and interactions with animal owners/caretakers.3

The systems concept views a community as a living creature made of many parts with each component supporting a function essential to the whole.2,4 Organizations and individuals focusing on the care of animals may work alongside or augment human-focused initiatives within a community. A systems approach to community engagement ‘often involves partnerships and coalitions that help mobilize resources and influence systems, change relationships among partners, and serve as catalysts for changing policies, programs, and practices’.1 Applying the systems perspective to the identification of and collaboration between assets in a community increases the impact on animals and people. In addition, as described in the CDC’s Health Equity Guide, prioritization of needs and promotion of health equity within communities should guide the distribution of resources.5

The concept of community can also be viewed through social, virtual, and individual perspectives. Animal owners or caretakers are likely to identify as part of a community or communities not entirely defined by their relationship to animals. The social perspective defines groups within a community by their social and political affiliations. These affiliations can link individuals to other individuals, community organizations and the leaders of those organizations.2 Applying the social perspective of the community to VCE endeavors can help programs identify inconspicuous community leaders through their social ties.

With increasing engagement through technology, the community is not restricted to geographical boundaries. The virtual concept of community also accounts for community through affiliation with groups that exist on social media networks. Individuals may identify as a part of a virtual community based on common interests, including pet ownership.2

The individual conception of community is self-defined and may be based on geography, activities, behaviors, goals for animals (e.g. dog park attendance, virtual pet care forum membership, or community cat colony managers), or as part of a community in which animals serve a particular role (e.g. assistance, emotional support, sports, show, and production). The way in which an animal caretaker views themselves and their animals informs their community identity. For example, animal caretakers may not strongly identify with others around them who own pets (e.g. keeping chickens for food in contrast to keeping backyard pets), which could influence their decision to participate or not participate in programs or opportunities. In many instances, animals and their care activities serve as the conduit for the formation of social support networks and a source of personal identity for those involved.

VCE programs involve many interested parties, including animals, animal caretakers, veterinarians, organizations, governments or individuals who contribute funding or services, community members indirectly impacted by resource allocation or activities, animal sheltering organizations, and students or investigators benefiting from education or research data acquired through the engagement process. Others who do not fall into these categories may also engage with or be impacted by projects in meaningful ways.

Veterinarians employed by animal welfare organizations, commonly identified as shelter veterinarians, are increasingly involved in caring for community animals who belong to clients unable to access and afford veterinary care.6 The expanding mission of animal sheltering organizations, many of whom now provide low-cost services to the public as well as veterinary services for unowned animals such as community cats, reflects a recognition that such populations are potential sources of shelter intake. Thus, the best outcome for many companion animals is to remain in their loving homes and family units, rather than shelter admission or rehoming. These services illustrate the role of the shelter as a public health resource that improves human and animal welfare across communities.

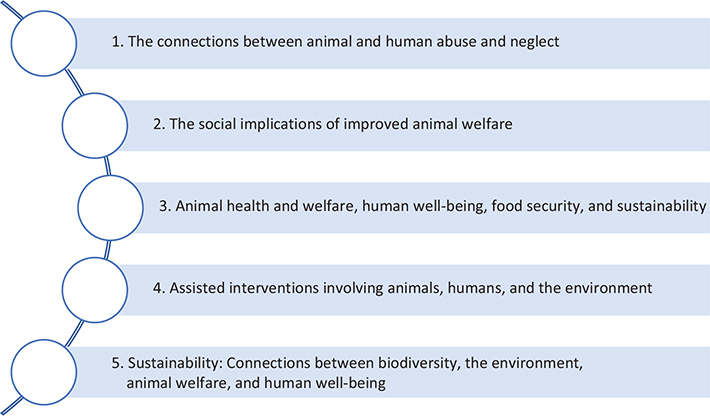

One Health and One Welfare

The mutual relationship between people, animals, and the environment is referred to as One Health.7 One Welfare is defined as the ‘interconnections between animal welfare, human wellbeing and their physical and social environment’.8 The theoretical frameworks that One Welfare utilizes are interdisciplinary, and emphasize the interconnection between animal, human, and environmental health as a critical component of maximizing impact in any one discipline (see Fig. 1.2). A One Welfare approach, in conjunction with the One Health initiative, recognizes the intertwined nature of human, animal, and social welfare, where there has historically been artificial compartmentalization. The health and welfare of companion animals have a direct effect on the health and welfare of their owners, and the community/environment in which they live together.9 The concepts of One Health and One Welfare are a core foundation for discussing and implementing the principles of VCE.

Fig. 1.2. Theoretical frameworks of the One Welfare concept emphasize the interconnections between animal, human, and environmental health to maximize impact across disciplines. Adapted from Pinillos et al.9

Communities benefit when the animals they care for are strong and healthy. Animals provide significant social and health benefits to people.10–12 Animals can also be a source of stress and disease when their caretakers do not have access to basic services, preventive medications, or veterinary care.13 Geographic location, social status, and economic status have significant impacts on human health14; these same factors help determine the health of the animals in communities.15,16 A basic tenet of One Health is that improving environmental and animal well-being also improves human well-being.7

Audience for this document

The intended audience for this document includes individuals engaged in executing and/or participating in community engagement programs which deliver animal health services through a partnership of veterinary professionals and community members. Because animal health services are provided by these programs, it is essential veterinarians are involved in overseeing veterinary care and are engaged in their planning and implementation. However, this resource is not intended only for veterinary use. Other target audiences include university faculty, staff, and students, animal welfare organizations, granting and funding organizations, community partners, and animal shelters engaged in work in their communities, among others.

To help clarify our intentions and align understanding for all audiences, we have included a glossary of terms at the end of this document. At their first use, glossary terms appear with a hyperlink to Appendix A: the glossary.

Scope of this document

Many types of animal-related engagement occur in communities. The scope of this resource is for programs focused on the delivery of animal health services in conjunction with veterinary professionals. Other resources may be more targeted to other types of community engagement activities, such as humane education programs, animal-assisted interventions, and service-animal programs. For example, the International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations (IAHAIO) provides best practices in animal-assisted interventions.17 The Association of Shelter Veterinarians (ASV) offers guidelines specific to animal sheltering organizations, including some guidance about how shelters engage with communities.18 The concepts presented here may also be helpful and relevant to these and other community animal activities.

While it is recognized that VCE occurs internationally, there are limitations to the breadth and depth of what we could include in this resource. Many challenges may exist in the universal application of these principles worldwide, and aspects of the discussion may be most reflective of work performed in the United States (US) by US care providers, due to overrepresentation in this document’s authorship and review. However, international programs may find that this resource can assist in evaluating program design and implementation.

Finally, the authors recognize that policy and advocacy for increased access to animal-related services are essential and necessary within this field and applaud the organizations leading this effort. Guidelines for engaging in advocacy work, both within a community and at a national level, are beyond the scope of this document and are discussed by others.19,20

Ethical frameworks

Ethics in human healthcare has been distilled into three basic principles: beneficence/non-maleficence, which translates most easily into ‘first do no harm’; justice, which means fairness to all, without bias or discrimination; and respect for the person, including respect for the life, autonomy, and dignity of patients.21 Many factors that present ethical and societal challenges in human healthcare are also present in the delivery of clinical care to animals, including health inequities, informed consent, and accessing care.22 Additionally, animals cannot advocate for themselves, provide consent, or exercise autonomy in healthcare choices. Veterinary medicine relies on proxy evaluation of animal welfare to inform recommendations and decision-making. Therefore, it is the responsibility of those engaging in healthcare activities to practice with integrity.23

Fraser’s practical ethic for animals considers One Welfare and One Health concepts and is easily applied in veterinary settings24 (see Table 1.1). This framework focuses on four main principles: providing good lives for the animals in our care, treating suffering with compassion, being mindful of unseen harm, and protecting the life-sustaining processes and balances of nature.25 While this framework was designed for animals, each principle may also be applied to people, communities, and the environment impacted by VCE.

| Ethical Principle | Application of Principles |

| Provide good lives for the animals in our care | A ‘good life’ should be achievable in principle for animals, even if it will require enormous change in practice |

| Treat suffering with compassion | Identify virtues of compassion and mindfulness that should be applied in relevant contexts |

| Be mindful of unseen harm | People who act with compassion and mindfulness should be motivated to avoid and mitigate suffering and unseen harms where they can, while recognizing that some such harms will still exist |

| Protect the life-sustaining processes and balances of nature | This is a call to action in recognition of the great and lasting harm to all inhabitants of the planet which seems likely if action is not taken |

Animal welfare frameworks

The Five Freedoms has informed animal welfare assessments across a wide array of animal-related environments since the late 1960s.26 The Five Domains is an updated reworking of this framework, with an emphasis on increasing positive experiences and recognition of an overall mental state27 (see Table 1.2). In some settings, these frameworks are utilized as a means of evaluating facility or institutional success in animal care. In VCE settings, they are better used to design interventions that support and maintain positive welfare states while also maintaining the human-animal bond present between the animal and the caretaker. Additionally, clinical tools such as pain scales and quality of life assessments can enable treatment decision-making in the context of VCE programs when they are providing individualized clinical services.28–33

| Five Freedoms34 | Five Domains Model for Animal Welfare27 |

| Freedom from hunger and thirst by ready access to water and a diet to maintain health and vigor | Good nutrition, access to fresh water and a diet to maintain health and vigor. Minimize thirst; enable eating to be a pleasurable experience |

| Freedom from discomfort by providing an appropriate environment, including shelter and an appropriate resting area | Good environment; access to shelter, shade, suitable housing, good air quality, and comfortable rest areas. Minimize discomfort, and promote thermal, physical, and other comforts |

| Freedom from pain, injury, and disease by prevention or rapid diagnosis and treatment | Good health: prevention and rapid diagnosis and treatment of disease or injury, fostering good biological functioning. Minimize aversive experiences such as pain and nausea; promote physical activity, vigor, and strength |

| Freedom to express normal behavior by providing sufficient space, proper facilities, and an appropriate company of the animal’s own kind | Appropriate behavior: access to sufficient space, proper facilities, compatible company, and appropriately varied conditions. Minimize threats and unpleasant restrictions on behavior; promote engagement in rewarding activities |

| Freedom from fear and distress by ensuring conditions and treatment which avoid mental suffering | Good feeling (positive mental experiences): access to safe, species-appropriate opportunities to engage in pleasurable activities and experiences. Promote comfort, pleasure, interest, confidence, and a sense of control |

Applying animal welfare and ethical frameworks is essential for individuals and organizations participating in the design, delivery, and evaluation of VCE, to ensure practitioners have considered not only the ethics of caring for an animal but also the priorities and circumstances of humans who represent the animal. The program goal must be an improvement in positive welfare states for both human and animal participants.

Engaging with animal caretakers

To understand whether engagement will be helpful, a VCE activity should begin with a needs assessment. This assessment is a structured inquiry at the level of the community that helps project leaders and community members identify assets and gaps in services or resources in the community.35 In the VCE context, the assessment is focused on animal health services. This process should be performed before a project is started and should center on the perspective of animal caretakers. The people whose animals receive services through community engagement projects require genuine, authentic representation during all phases of the engagement, including inception and design. Representation includes allowing caretakers to act as advocates for their animals, providing input into which services are needed or desired, as well as helping to define project success. Repeat assessments should be performed regularly as a means of program evaluation and recalibration.

Effective and accessible communication is essential to build relationships with animal owners and to identify community goals. The primary languages spoken by those implementing engagement projects and animal owners or caretakers receiving services may be different. In these cases, the inclusion of bilingual personnel is critical since important nuances that deepen understanding between project partners may otherwise be lost. Beyond language, community pet owners and caretakers may have variable access to modes of communication or have different preferences, such as text messaging versus email or phone calls. Choosing the modality that community members can easily access and engage with may need to include recognizing literacy or technological literacy challenges.36

In every project, it is essential to communicate the longevity and scope of services provided to individual project participants. Defining the scope of services that an intervention will or won’t provide is particularly important for clinics with a narrow focus (such as wellness and preventive care); project leaders should be prepared to answer questions and refer owners for care that falls beyond the scope of that engagement (such as care for ill or injured animals). Defining the longevity of the program or how long the community can continue to rely on the project is particularly important for veterinary engagement programs that regularly provide pet food, litter, and other necessities. Owners relying on the project may require additional assistance to locate alternative sources when those provisions become unavailable. Ideally, community engagement projects that provide any kind of service for pet owners include a roadmap for continued community participation and sustainability. Shorter projects ideally operate in the context of larger relationships.

Interdisciplinary collaborations have shown to be very helpful for healthcare, even decreasing errors and improving outcomes.37 Fostering relationships between veterinary and human health providers can be especially helpful when barriers and challenges in interprofessional work are recognized. For example, those engaging in projects involving difficult aspects of pet ownership, such as humane euthanasia or pet hospice care decision-making, generally benefit from including a social worker, especially one trained in the veterinary field.38,39 Social workers can also help veterinarians to understand how a pet impacts their owner’s mental health and distinguish between typical and complicated grief,38 as well as connect individuals to other resources in the community.

Engaging with animals

Animals frequently share the same social determinants of health as their owners, including geographical, economic, and environmental factors.40,41 Animal health projects engaging with communities should be prepared by assessing access to veterinary care (AVC) within the target community, including veterinary care deserts, cost or transportation barriers, and the presence of other engagement projects or community resources, such as shelters or not-for-profit clinics. Projects should be prepared to address the common health concerns faced by animal populations in that location; these concerns may vary between communities, geographical regions, animal species, and populations.

Veterinary interventions provided through community engagement projects are most effective when they follow a spectrum of care or contextualized care model.42–45 Insisting on highly technological and invasive modalities or referrals to tertiary care facilities and specialists because it is perceived as the ‘best care available’ will result in fewer animals being helped and may provide little benefit over more economical or accessible approaches.

There is growing effective care evidence showing lower cost treatment options may be as successful as higher cost options.46,47 The spectrum of care practice emphasizes the importance of collaboration and information exchange between the veterinary team member and animal caretaker, and relies on excellent physical exams, history taking, communication skills, and culturally responsive care (also known as cultural humility, discussed further below).42 Clearly communicating the scope and longevity of the project to community members helps owners select from the care choices available for their animals and understand the limits to care the project can provide.

A least harm approach to effective animal care is recommended. This approach provides care that alleviates distress or suffering even when the medical or behavioral problem may persist, the diagnosis may go unconfirmed, or owner compliance may be uncertain. Some intervention (such as pain medication) is better than not intervening just because optimal care (such as pre-treatment bloodwork) is unavailable. A least harms approach also includes providing only necessary interventions with attention to least intrusive minimally aversive principles.48 For example, requiring a rectal temperature for healthy animals with no history of illness before vaccination is generally unnecessary, increases patient discomfort, may risk staff safety, and prolongs each visit. Full disclosure to owners about the positive and negative implications of different treatment plans should be discussed regardless of income or education level in an accessible way. Choice and autonomy should be provided about how to move forward, even if it involves not utilizing the current clinic options.

Within animal health projects, attention to animal well-being includes close attention to fear, anxiety, and stress (see review by Lloyd).49 Fear Free® Training50 and Low Stress Handling®51 available for veterinary and animal shelter settings are very relevant to VCE activities in other settings. Provisions to decrease pain, stress, and anxiety are important in any project but are particularly critical in VCE projects involving elective surgery. Many economical and effective pain, sedation, and anesthesia protocols are available.52–55 Budgetary constraints do not excuse inadequate pain management in any setting.

Animals impacted by a project do not choose to participate. Owners and caretakers provide consent on behalf of the animals in their care and need to be given all information required for informed consent before participating. Project leaders, educators, and researchers should be subject to and seek official ethical review (e.g. IACUC, IRB, etc.) whenever possible and ensure the positive welfare of animals in teaching or scientific interventions. As part of this review, informed consent for training and/or research and the use of video or images must be obtained. When the VCE project involves oversight by more than one municipality or institution, the project should be subject to whichever ethical norms are the most stringent (see Chapter 6).

The primary goal of all VCE projects should be to enhance the well-being of animals and families in that community. Projects with secondary goals, such as research or education, must also primarily preserve and enhance animal and human welfare. Decisions must be made by project leaders in collaboration with community members that minimize harm and maximize health benefits to individual animals and animal populations.

Engaging with communities

Community-engaged programs succeed when they maintain an asset-based ideology, also known as a strength-based ideology, that emphasizes the strengths or assets of communities and focuses on building relationships.56,57 This approach to community development focuses on what is ‘working’ in the community, instead of only what is ‘not working’, and empowers community members to harness individual and community strengths to enhance whatever services the engagement program might propose.

One of the key assets in a community are proximate leaders. A proximate leader is a part of the community or meaningfully guided by the community’s ideas, agendas, and assets, ‘not just exposed or studying a group of people and its struggles to overcome adversity’.58 Proximate leaders have the relationships, experience, and knowledge to develop approaches with sustainable impact on the community. They also have the ability to identify and leverage community assets that can be ‘overlooked or misunderstood when viewed through a dominant culture lens’.58

Maintaining an asset-based ideology and identifying proximate leaders are key components in counteracting the ‘savior’ mentality/complex in which an outside participant (or organization) perceives their involvement as having an exaggeratedly beneficial impact, and/or that their participation deserves community gratitude. VCE programs that focus on ethical principles and nurturing mutually beneficial relationships naturally become less exploitative and more equitable.

Authentic inquiry regarding the cultural and community beliefs surrounding the husbandry and care of animals, cultural definitions of ‘a good life’ for each species, and the significance of the animals to the local economy is critical. The human-animal bond is often defined as the close, mutually dependent relationship between a caretaker and the animal they are caring for.59 This bond may be valued or structured differently from species to species, culture to culture, or owner to owner. For example, beliefs around animal ‘ownership’, pets living inside the house, or euthanasia, may differ within and between communities.60

Learning about the community’s cultural diversity is part of authentic inquiry. Culturally responsive care and cultural humility training for project participants at all levels is encouraged; inviting members of the community to assist in providing participant orientation is particularly helpful. An understanding that the engagement project represents only a small part of the lived experience of community members helps to counteract the ‘savior’ mentality/complex that can accompany many interventions, both for participants and project leaders.

Within a community, there may be different sub-groups and views. It is important to seek out authentic representation from the project’s community partnerships. In other words, care should be taken to not automatically assume that community-based agencies (such as SPCAs or veterinary clinics) have the same goals as the community members accessing program services. Accessing a community’s social network, defined here as the system of social communication within the community, can help project leadership identify influential community members who may be interested in participating in the project. Creating partnerships with informal or formal community leaders increases impact and allows for more genuine community participation.

Other interested parties

Project partners often have multiple and sometimes competing goals. Projects often include educators, those receiving instruction, and/or researchers, who directly interact with animals and caretakers in the community. Funding agencies, non-governmental or faith-based organizations, and institutions of higher education also may have a vested but indirect interest in the activities and outcomes of VCEs.

Granting organizations, in addition to fulfilling their missions, receive recognition and media coverage.

Grantors and partner organizations, especially universities, should insist on some community orientation or cultural sensitivity training as part of their requirements for funding engagement projects. When services provided to community members are constrained by specific requirements from grantors, these constraints must be communicated to community leaders when designing the projects and individuals seeking services as part of information about the scope of services. Granting organizations should account for the time and effort it takes to develop a program that aligns with community engagement principles in grant timelines and support.

All interested parties gain something from the experience, whether education, field experience, research data, grants, and/or accolades that help advance careers and livelihoods. Both education and discovery are essential to advance the animal welfare field and are frequently the impetus for engagement projects. VCE programs must incorporate an underlying and unequivocal commitment to improving animal welfare. When done properly, these projects thoughtfully provide for community-identified animal needs while supporting experiential learning in animal healthcare and respectful interaction with diverse people.

Transparency and program evaluation

As a component of ethical, transparent practice, all program goals (e.g. education, research, future project plans, fund-raising, and media engagement) should be openly shared with the community and individual animal caretakers prior to initiating the project. Furthermore, to determine whether the project is having the desired effect on the animals and caretakers, every project should include a clear and communicated plan for assessing the project’s interventions and outcomes.

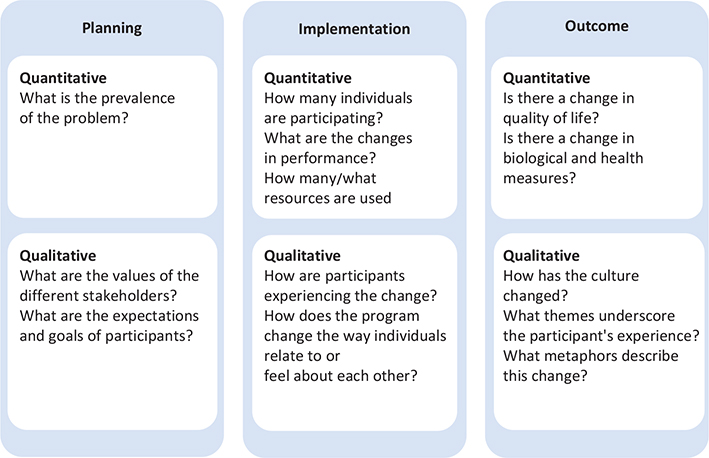

Programmatic evaluation can take many forms, including surveying pet owners, surveying community leaders, or assessing the community’s population of animals for health markers, and can include anthropological, sociological, epidemiological, participatory, or other methodologies. The timing of assessment can be continuous or occur at regular intervals. Projects should not wait until the proposed ‘end’ of the engagement to decide to collect feedback; plans for evaluation should be part of the initial development of any programs or interventions.

Once performed, the results of assessments, whether positive or negative, must be shared with community members in full transparency. When assessment prompts project leaders or community members to consider changes to the project’s original plan or scope, these changes should be proposed and agreed upon by all affected parties. A plan for further assessment should be made at that time (see Chapter 6).

References

| 1. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Principles of Community Engagement. CDC/ATSDR Committee on Community Engagement. 1st ed. 1997. |

| 2. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. 2011. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2023. |

| 3. | Wood L, Martin K, Christian H, et al. The pet factor – companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122085 |

| 4. | Thompson B, Kinne S. Chapter 2: Social change theory: applications to community health. In: Bracht N, ed. Health Promotion at the Community Level: New Advances. Sage Publications. 2nd ed. 1998:29–28. |

| 5. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Division of Community Health. A Practitioner’s Guide for Advancing Health Equity: Community Strategies for Preventing Chronic Disease. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. |

| 6. | Shelter Animals Count. Community Services Data. 2022. https://www.shelteranimalscount.org/community-services-data-report-2022. Accessed May 24, 2024. |

| 7. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). One Health. https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/index.html. Accessed April 14, 2023. |

| 8. | One Welfare. About One Welfare. https://www.onewelfareworld.org/. Accessed April 13, 2023. |

| 9. | Pinillos RG, Appleby MC, Manteca X, Scott-Park F, Smith C, Velarde A. One welfare – a platform for improving human and animal welfare. Vet Record. 2016;179(16):412–413. doi: 10.1136/vr.i5470 |

| 10. | Christian HE, Westgarth C, Bauman A, et al. Dog ownership and physical activity: a review of the evidence. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(5):750–759. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.5.750 |

| 11. | Levine GN, Allen K, Braun LT, et al. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(23):2353–2363. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829201e1 |

| 12. | McConnell AR, Brown CM, Shoda TM, Stayton LE, Martin CE. Friends with benefits: on the positive consequences of pet ownership. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2011;101(6):1239. doi: 10.1037/a0024506 |

| 13. | LaVallee E, Mueller MK, McCobb E. A systematic review of the literature addressing veterinary care for underserved communities. J Appl Animal Welfare Sci. 2017;20(4):381–394. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2017.1337515 |

| 14. | Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6 |

| 15. | McDowall S, Hazel SJ, Chittleborough C, Hamilton-Bruce A, Stuckey R, Howell TJ. The impact of the social determinants of human health on companion animal welfare. Animals. 2023;13(6):1113. doi: 10.3390/ani13061113 |

| 16. | Neal SM, Greenberg MJ. Putting access to veterinary care on the map: a veterinary care accessibility index. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:219. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.857644 |

| 17. | International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations (IAHAIO). The IAHAIO definitions for animal assisted intervention and guidelines for wellness of animals involved in AAI [white paper]. 2018. https://iahaio.org/best-practice/white-paper-on-animal-assisted-interventions/. Accessed August 24, 2023. |

| 18. | The Association of Shelter Veterinarians (ASV). The guidelines for standards of care in animal shelters: second edition. J Shelter Med Commun Anim Health. 2022;1:1–76. doi: 10.56771/ASVguidelines.2022 |

| 19. | American Public Health Association. Top Ten Rules of Advocacy. https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/advocacy-for-public-health/coming-to-dc/top-ten-rules-of-advocacy#:~:text=Be%20brief%2C%20cle. Accessed August 14, 2023. |

| 20. | Golden SD, McLeroy KR, Green LW, Earp JAL, Lieberman LD. Upending the Social Ecological Model to Guide Health Promotion Efforts Toward Policy and Environmental Change. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2015:8S–14S. |

| 21. | Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Oxford University Press; 1979. |

| 22. | National Council for Mental Wellbeing. Addressing Health Equity and Racial Justice within Integrated Care Settings. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/resources/integrated-health-coe-toolkit-purpose-of-this-toolkit/. Accessed August 14, 2023. |

| 23. | Grimm H, Bergadano A, Musk GC, Otto K, Taylor PM, Duncan JC. Drawing the line in clinical treatment of companion animals: recommendations from an ethics working party. Vet Record. 2018;182(23):664. doi: 10.1136/vr.104559 |

| 24. | Fawcett A, Mullan S, McGreevy P. Application of Fraser’s ‘practical’ ethic in veterinary practice, and its compatibility with a ‘one welfare’ framework. Animals. 2018;8(7):109. doi: 10.3390/ani8070109 |

| 25. | Fraser D. A ‘practical’ ethic for animals. J Agri Environ Ethics. 2012;25:721–746. doi: 10.1007/s10806-011-9353-z |

| 26. | Brambell F. Report of the Technical Committee to Enquire into the Welfare of Livestock Kept under Intensive Conditions. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; 1965. |

| 27. | Mellor DJ, Beausoleil NJ, Littlewood KE, et al. The 2020 five domains model: including human–animal interactions in assessments of animal welfare. Animals. 2020;10(10):1870. doi: 10.3390/ani10101870 |

| 28. | Costa R, Hassur R, Jones T, Stein A. The use of pain scales in small animal veterinary practices in the USA. J Small Animal Pract. 2023;64(4):265–269. doi: 10.1111/jsap.13581 |

| 29. | Evangelista MC, Watanabe R, Leung VS, et al. Facial expressions of pain in cats: the development and validation of a Feline Grimace Scale. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19128. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55693-8 |

| 30. | Gardner M. Quality of life assessment and end of life decisions. In: Gardner M, McVety D, eds. Treatment and Care of the Geriatric Veterinary Patient. Wiley Blackwell/John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2017:297–310. |

| 31. | Mullan S. Assessment of quality of life in veterinary practice: developing tools for companion animal carers and veterinarians. Vet Med. 2015;6:203–210. doi: 10.2147/VMRR.S62079 |

| 32. | Oyama MA, Citron L, Shults J, Cimino Brown D, Serpell JA, Farrar JT. Measuring quality of life in owners of companion dogs: development and validation of a dog owner-specific quality of life questionnaire. Anthrozoös. 2017;30(1):61–75. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2016.1228774 |

| 33. | Yeates J, Main D. Assessment of companion animal quality of life in veterinary practice and research. J Small Animal Pract. 2009;50(6):274–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2009.00755.x |

| 34. | Farm Animal Welfare Council. Farm Animal Welfare in Great BritaIn: Past, Present and Future. Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs; 2009. |

| 35. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Community Needs Assessment. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fetp/training_modules/15/community-needs_pw_final_9252013.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2023. |

| 36. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Inclusive Communication Principles. https://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/Health_Equity.html. Accessed August 14, 2023. |

| 37. | Fewster-Thuente L, Velsor-Friedrich B. Interdisciplinary collaboration for healthcare professionals. Nurs Admin Quarter. 2008;32(1):40–48. doi: 10.1097/01.NAQ.0000305946.31193.61 |

| 38. | Holcombe TM, Strand EB, Nugent WR, Ng ZY. Veterinary social work: practice within veterinary settings. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2016;26(1):69–80. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2015.1059170 |

| 39. | Hoy-Gerlach J, Ojha M, Arkow P. Social workers in animal shelters: a strategy toward reducing occupational stress among animal shelter workers. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:734396. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.734396 |

| 40. | Card C, Epp T, Lem M. Exploring the social determinants of animal health. J Vet Med Educ. 2018;45(4): 437–447. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0317-047r |

| 41. | Patronek GJ. Mapping and measuring disparities in welfare for cats across neighborhoods in a large US city. Am J Vet Res. 2010;71(2):161–168. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.71.2.161 |

| 42. | Brown CR, Garrett LD, Gilles WK, et al. Spectrum of care: more than treatment options. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2021;259(7):712–717. doi: 10.2460/javma.259.7.712 |

| 43. | Fingland RB, Stone LR, Read EK, Moore RM. Preparing veterinary students for excellence in general practice: building confidence and competence by focusing on spectrum of care. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2021;259(5):463–470. doi: 10.2460/javma.259.5.463 |

| 44. | Skipper A, Gray C, Serlin R, O’Neill D, Elwood C, Davidson J. ‘Gold standard care’ is an unhelpful term. Vet Record. 2021;189(8):331. doi: 10.1002/vetr.1113 |

| 45. | Stull JW, Shelby JA, Bonnett BN, et al. Barriers and next steps to providing a spectrum of effective health care to companion animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253(11):1386–1389. doi: 10.2460/javma.253.11.1386 |

| 46. | McCobb E, Dowling-Guyer S, Pailler S, Intarapanich NP, Rozanski EA. Surgery in a veterinary outpatient community medicine setting has a good outcome for dogs with pyometra. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2022;260(S2):S36–S41. doi: 10.2460/javma.21.06.0320 |

| 47. | Perley K, Burns CC, Maguire C, et al. Retrospective evaluation of outpatient canine parvovirus treatment in a shelter-based low-cost urban clinic. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2020;30(2):202–208. doi: 10.1111/vec.12941 |

| 48. | The Association of Professional Dog Trainers (APDT). Position Statement on LIMA. https://apdt.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/position-statement-lima.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2023. |

| 49. | Lloyd JKF. Minimising stress for patients in the veterinary hospital: why it is important and what can be done about it. Vet Sci. 2017;4(2):22. doi: 10.3390/vetsci4020022 |

| 50. | Fear Free. Fear Free Shelters. 2023. https://fearfreeshelters.com/. Accessed April 6, 2023. |

| 51. | Cattle Dog Publishing. What Is Low Stress Handling? https://cattledogpublishing.com/why-and-what-is-low-stress-handling/. Accessed April 13, 2023. |

| 52. | Costa RS, Karas AZ, Borns-Weil S. Chill Protocol to Manage Aggressive & Fearful Dogs. https://digital.cliniciansbrief.com/digital-edition/clinicians-brief-may-2019#48592. Accessed April 13, 2023. |

| 53. | Griffin B, Bushby PA, McCobb E, et al. The association of shelter veterinarians’ 2016 veterinary medical care guidelines for spay-neuter programs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016;249(2):165–188. doi: 10.2460/javma.249.2.165 |

| 54. | Ko JC, Berman AG. Anesthesia in shelter medicine. Topics Compan Animal Med. 2010;25(2):92–97. doi: 10.1053/j.tcam.2010.03.001 |

| 55. | The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). Spayathon for Puerto Rico. 2019. https://maddiesmillionpetchallenge.org/wp-content/uploads/Spayathon-Information-Packet.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2024. |

| 56. | Blickem C, Dawson S, Kirk S, et al. What is asset-based community development and how might it improve the health of people with long-term conditions? A realist synthesis. SAGE Open. 2018;8(3):215824401878722. doi: 10.1177/215824401878722 |

| 57. | Kretzmann J, McKnight J. Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets. ACTA Publications; 1993. |

| 58. | Jackson A, Kania J, Montgomery T. Effective change requires proximate leaders. Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.48558/DBNF-V067. |

| 59. | Fine AH. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice. 3rd ed. Elsevier Academic Press; 2010. |

| 60. | Elmore RG. The lack of racial diversity in veterinary medicine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;222(1):24–26. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.24 |

Chapter 2: Principles of veterinary community engagement

*Adapted from Principles of Community Engagement 2nd edition1

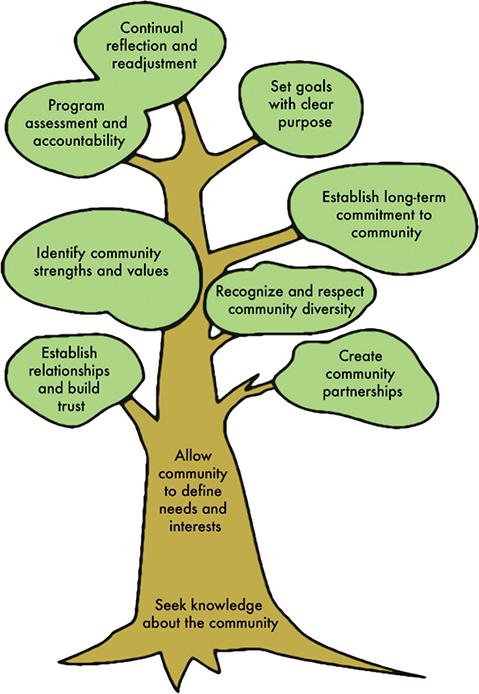

Key objective: This chapter outlines nine pillars of veterinary community engagement (VCE) (Fig. 2.1), modeled after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Principles of Community Engagement (PCE) for human health.1

Fig. 2.1. Visual diagram of nine pillars of veterinary community engagement, modeled after the CDC’s principles of community engagement for human health.1

Introduction

Veterinary engagement in communities with limited access to care is vital for the health and wellness of both animals and humans. Even well-intentioned programs can have negative impacts on individuals and communities. Thoughtful and intentional engagement practices are needed to ensure ethical and sustainable community initiatives. Building trust and creating lasting relationships with community members, as well as community organizations, is fundamental for program success.

In the United States, veterinary practices have generally been located in white, affluent communities, with about 93% of veterinary doctors identifying as white.2 Historically, the veterinary medical industry has poorly supported inclusivity in animal ownership, instead focusing on the care of pets of owners with means to access care and largely ignoring those that could not.3,4 Likewise, animal control and welfare efforts in marginalized communities in the United States have frequently focused on animal seizure and surrender rather than owner engagement.5,6 For both fields, these practices have resulted in the promotion of attitudes of superiority/inferiority and created barriers to trust with people caring for animals in underserved communities. As a result, communities may be reluctant to engage with entities that remind some of their members of previous poor experiences. It is essential to increase access to veterinary care (AVC) in diverse communities, as well as increase diversity in the veterinary profession.

In order to promote equitable relationships and prevent barriers to trust, we offer these nine principles or pillars of VCE modeled on the Principles of Community Engagement.1 Although these pillars are numbered, they are not intended to be followed in a linear approach. In fact, the activities discussed in the principles should occur simultaneously and repeatedly throughout the process of developing, implementing, assessing, and continually renewing a VCE project.

Principle 1

‘Become knowledgeable about the community’s culture, economic conditions, social networks, political and power structures, norms and values, demographic trends, history, and experience with efforts by outside groups to engage… Learn about the community’s perceptions of those initiating the engagement activities’.1

Using both qualitative and quantitative measures, authentic inquiry should be employed to learn as much as possible about a community – including how they perceive their pets – to foster a successful partnership between an organization and a community. Additionally, VCE leaders should seek to understand how the community perceives the benefits and costs of participating in the project, in order to address misconceptions and concerns from the beginning.

Principle 2

‘Go to the community, establish relationships and build trust, work with the formal and informal leadership, and seek commitment from community organizations and leaders to create processes for mobilizing the community’ in an ethical and evidence-based way.1

Similar to community engagement in human healthcare, programs succeed and grow when members of the community are active partners in their planning and implementation. This process requires fostering relationships built on trust and mutual respect between an organization or individual and the community’s interested parties. There are many actions, from meeting at a location within the community to identifying multiple interested parties to include in the planning process, that signal and facilitate the establishment of a solid working relationship. Other examples include the provision of appropriate, close supervision of trainees and post-operative support for complications resulting from student learning in VCE clinical settings. An approach which takes into account the animal, caretaker, and evidence-based contextualized care and high ethical principles should be employed to provide optimal client and patient welfare.

Principle 3

Partner with the community to create change and improve community health and animal welfare.1 Recognize how, as a program leader and care provider, your identity influences this partnership.

Partnership implies mutual respect, reciprocity, and investment in meeting collectively established goals. Members of the community must be active and respected participants in the project. Veterinarians, for example, should recognize the power inherent in their role, as well as how their past experiences, identity and personal values may impact their perspective. Ideally, veterinarians work with partners to coordinate the expected healthcare activities, generate ideas, and understand community initiatives from the beginning. Organizations need the flexibility to listen and adapt to community feedback. Community needs assessments in partnership should identify both needs and assets that exist in that community and recognize the community’s strengths as well as its challenges. Power dynamics between outside organizations and community members are often disproportionate; therefore, it is crucial to work equitably and acknowledge any power differentials that may impact relationships.

Principle 4

‘Remember and accept that collective self-determination is the responsibility and right of all people in a community. No external entity should assume it can bestow on a community the power to act in its own self-interest’”.1 Organizations that wish to engage a community as well as individuals seeking to effect change must be prepared to release control of actions or interventions to the community and be flexible to meet its changing needs.

Maintaining an asset-based, community driven approach while engaging with communities leads to equitable and sustainable relationships. The ‘savior’ mentality or organizational overreach leads to community disengagement and inequitable power imbalances. Autonomy of community members to make decisions that align with their cultural/ethical priorities is essential to building a strong relationship. For example, while requiring animals to be spayed or neutered in order to receive low-cost urgent care may help an organization meet their mission to decrease pet overpopulation, it may also jeopardize engagement by removing owner agency and participation, compromising community and animal care.

Principle 5

All aspects of community engagement must be designed to recognize and respect diversity within the community and the partnership. Acknowledge how identity impacts planning, design, and implementation.1

The diversity of a community is recognized in many variables, from socioeconomic status to shared culture and history, and more. Recognition of the ways in which community members differ plays a major role in how participants engage. For example, language is a common barrier to accessible veterinary care. A project in a community where many languages are spoken will need to ensure that verbal or written communication is not a barrier to care access for any subset of the community.

Principle 6

Be clear and transparent about the purpose or goals of the community engagement project and recognize that interested parties will come to a partnership with equally important but different goals.1

Representatives of the partner community should be actively engaged in goal setting and defining priorities. All participating individuals and organizations should be able to articulate why they wish to be involved. The impetus for veterinary engagement is less often the result of a legislative change and more often the result of organizations wishing to expand or fulfill their mission in a different fashion. Examples might include a non-profit organization which received a grant to provide vaccinations or a veterinary school that wishes to improve the hands-on training their students receive. VCE projects benefit from clear goals and an agreed upon scope of services, such as a vaccine clinic to reduce infectious disease incidence in the community or a community clinic to improve access to veterinary care or animal care in general. As discussed in the CDC’s PCE document for human healthcare settings,7 a narrower focus leads to a more easily managed project while a broader focus can lead to a greater impact within the community as a whole.

Principle 7

‘Community engagement can only be sustained by identifying and mobilizing community assets and strengths and by developing the community’s capacity and resources to make decisions and take action’.1

Every community has specific assets, strengths, and resources, as well as concerns and challenges highlighted by passionate individuals and organizational advocates. VCE projects wishing to develop sustainable community initiatives should harness community strengths and assets, and foster community growth and development. For example, partnering with a transportation business based in the community to provide rides to a clinic for owners and their pets both harnesses a community-based strength and promotes its growth. A community-based pet food pantry with a solid base in development may be able to take ownership of the solicitation of potential donors and collection of donations from external organizations.

Principle 8

Community collaboration requires a long-term commitment to have the best chance at a measurable and sustainable impact.1

Many veterinary engagement initiatives begin with a specific funding opportunity which may only enable the execution of a single event. However, the health and care of animals are best served when community collaboration occurs over time and with an eye to sustained efforts and relationships. Successful partnerships are built on a foundation of trust and mutual respect; new partnerships take time to establish and in general, programs are more effectively planned with a commitment to sustainability, not in reaction to short-term funding availability. Funding organizations are specifically encouraged to commit support over periods more conducive to authentic partnerships (e.g. years or multiple years) and to promote VCE projects in line with these principles. Any events or projects intended on a shorter timeline should be part of a larger relationship or commitment to the community itself.

Principle 9

Successful community collaboration requires continual reflection, both individually and as a group. Accountability and assessment of VCE programming is crucial for continued success.

Collaborators should take time to establish the definition of a ‘successful program’ in the eyes of all interested parties, recognizing priorities may differ. Identifying the criteria, concerns, and limitations prior to starting a program is ideal. Assessment of community engagement requires both individual and organizational reflection at multiple time-points. For individuals, recognizing internal bias and judgment is crucial to growth and fostering connection. Additionally, structured reflection is essential to building skills in interpersonal communication, problem solving, self-awareness, and a sense of civic responsibility. In particular, as healthcare providers, veterinarians are encouraged to reflect on their role in the face of increasingly complex challenges in access to care for communities. Program-level reflection includes evaluation of data to assess impact and shape evolution of the project. Sharing and connecting with others about experiences, successes, and failures supports continued learning within and outside of the community and can improve community engagement programming on a much larger scale.

In conclusion, sustainable community engagement efforts are fostered through shared connections, relationship building and deep listening. Veterinarians and other animal healthcare professionals experience burnout and moral distress at a higher rate than other professions.8–12 By nature, VCE programs that are delivering medical care rely on these professional providers. It is important for all participants to routinely connect with partners and peers about goals, expectations, successes, and challenges to promote long-term sustainable relationships.

Applying these pillars will aid in the process of VCE by centering the voices and lived experiences of animal caretakers and other interested parties in the community. If missteps or mistakes are made, leaders should acknowledge responsibility and maintain open communication to find mutually beneficial solutions. Recognizing and reflecting on internal bias, as well as the impacts of institutional and structural privilege and racism, is a lifelong process.

References

| 1. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. 2011. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2023. |

| 2. | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Characteristics by Race and Ethnicity. 2019. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/race-and-ethnicity/2019/home.htm. Accessed April 7, 2023. |

| 3. | LaVallee E, Mueller MK, McCobb E. A systematic review of the literature addressing veterinary care for underserved communities. J Appl Animal Welfare Sci. 2017;20(4):381–394. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2017.1337515 |

| 4. | The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). Pets for Life – A New Community Understanding. https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/2012-pets-for-life-report.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2023. |

| 5. | Hawes SM, Hupe T, Morris KN. Punishment to support: the need to align animal control enforcement with the human social justice movement. Animals. 2020;10(10):1902. doi: 10.3390/ani10101902 |

| 6. | Marceau J. Beyond Cages: Animal Law and Criminal Punishment. Cambridge University Press; 2019. |

| 7. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Principles of Community Engagement. 1st ed. 1997. |

| 8. | Andrukonis A, Protopopova A. Occupational health of animal shelter employees by live release rate, shelter type, and euthanasia-related decision. Anthrozoös. 2020;33(1):119–131. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2020.1694316 |

| 9. | Merck Animal Health. Merck Animal Health Veterinary Wellbeing Study III. https://www.merck-animal-health-usa.com/about-us/veterinary-wellbeing-study. Accessed August 24, 2023. |

| 10. | Neill CL, Hansen CR, Salois M. The economic cost of burnout in veterinary medicine. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:814104. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.814104 |

| 11. | The Association of Shelter Veterinarians (ASV). ASV Member Survey Reveals Profound Concern with Shelter Veterinarian Retention and Offers a Glimpse into Solutions. https://www.sheltervet.org/assets/PDFs/Survey%20Results%20and%20Member%20Discussion%20Summary.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2023. |

| 12. | Tomasi SE, Fechter-Leggett ED, Edwards NT, Reddish AD, Crosby AE, Nett RJ. Suicide among veterinarians in the United States from 1979 through 2015. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019;254(1):104–112. doi: 10.2460/javma.254.1.104 |

Chapter 3: Ethical considerations for veterinary community engagement

Key objective: This chapter outlines core ethical considerations for veterinary community engagement (VCE), including an emphasis on training programs.

Introduction

There is increased recognition among academic institutions and large non-profit organizations of the many benefits of VCE for applied training opportunities for veterinary professionals and increasing access to care. Robust opportunities are available but many fail to recognize the complexity of creating authentic partnerships or to subscribe to foundational animal welfare and ethical frameworks. Integrating these nine pillars into the program design, training opportunities, and interpersonal interactions with community leadership and individuals is a complicated process that takes time and thought. The ultimate goal is that all participants are in a better place than when they came to the partnership.

Program oversight

VCE programs must utilize qualified animal healthcare providers who have relevant licensure and are familiar with the legal restrictions for veterinary practice. In some programs, provision of medical advice may be provided through paraprofessionals or lay people; however, the program should have written protocols and consistent oversight by a veterinarian who has approved this provision of care, and who is available for consultation, questions, or follow-up. This model of veterinary oversight is commonly practiced in population settings such as animal shelters to optimize efficient high-quality care delivery.1 In addition to providing and documenting medical records, programs must identify and adhere to local, regional, and national laws beyond those directly related to veterinary services.

Program design

Cultural humility

Developing cultural humility is more than a recognition that one group may be different from another or from the prevailing norm in the region or community. It is common to attribute differences to cultural, moral, or ethical factors, but community conditions are determined by economic, social, and political factors as much as behaviors and beliefs.2,3 Acknowledging how historical power and privilege have shaped communities and informed community-engaged partnerships is essential to all engaged work (Principle 5). It is especially important when considering the history of academic work or research in communities with fewer resources.4,5

Caregiving and decision-making

In addition to the ethical and welfare frameworks presented in Chapter 1, VCE program design must be based on principles of empowerment of individuals and communities to play an active role in defining goals of the program and the interactions and the care provided to patients (Principle 6). Animal caretakers must be involved in decision-making at all levels and points in time. Every act is a collaboration which recognizes the value of all participants and recognizes that no single entity can accomplish what they are able to do together.

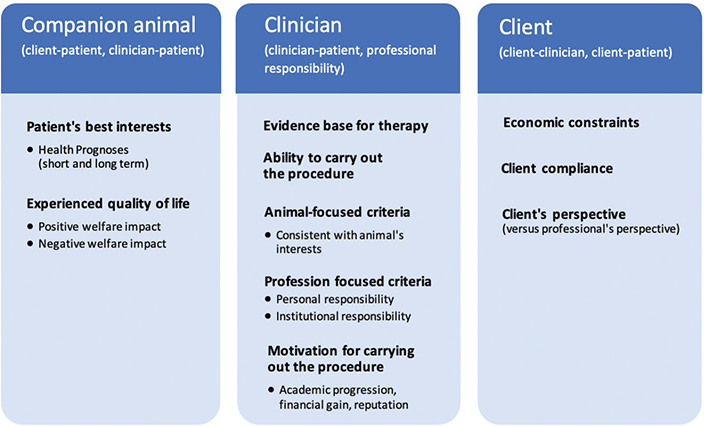

In human medicine, an emphasis on patient and family-centered care has shifted the focus from the physician as the provider to the patient and family unit to a model in which patients and families partner with the physician in attaining successful healthcare outcomes.6 This shift in focus is relevant in many veterinary contexts. A Family Quality of Life (FQoL) approach to veterinary clinical decision-making takes family-centric, patient-centric, and external factors all into account.7 The FQoL approach is particularly applicable in the community-engaged clinic context, where the animal caretaker may take a more active role in the provision of care at home due to resource limitations or patient/client preferences. An adapted diagram for veterinary contexts is shown in Fig. 3.1.

Fig. 3.1. Diagram adapted from Catalyst8 describing the concept of patient and client-centered care as it relates to veterinary medicine and clinical decision-making.

Scope of the work

Programs should consciously define the scope and capacity of the program to do compassionate work that reflects animal welfare principles (Principle 6). Optimal outcomes include a broad spectrum of treatment options and educational opportunities; animal welfare should be central to this decision-making process and take into account all aspects of patient management, including post-operative care and follow-up.

In addition to providing evidence-based contextualized care, programs should aim to provide positive experiences for human and animal participants in the context of a clinical interaction. Examples include incorporating positive reinforcement techniques in animal handling, providing appropriate medical services for diagnosed conditions, and ensuring nutritional support adequate for life-stages or other needs.9,10

Provision of care relies on the investment of resources by the family unit as well as the clinical program (Principle 3). Clinical decision-making should always involve a clear understanding of the level of investment required of all interested parties (see Fig. 3.2). There should be clear criteria for what an optimal outcome looks like for each party. An overall outcome that might seem ‘good enough’ for the clinician in the context of a training program or constrained resources might not adequately meet the overall welfare needs of the animal or the caretaker or the community as a whole.

Fig. 3.2. Diagram showing the key interested parties, relationship domains, and criteria to be considered in veterinary ethical decision-making. Adapted from Grimm et al.11

Events and the scope of programming must be coordinated with partner organizations already acting in the community to be considered engaged work. This coordination prevents overlapping of services and creates synergy and efficiency between engaged organizations and the community they serve. Providing services in a location without a consistent veterinary presence does not necessitate a decreased quality of care or a lack of protocols. In fact, well-structured and supervised care by trained animal care staff and trainees can often accomplish highly effective care.

Client recruitment and engagement

Selection of participants in programs should not default to those most available or convenient for medical care providers. Programs should also be designed to protect human and animal participants from needing to expend efforts or expenses beyond what is a reasonable expectation of a community member. This goal is accomplished by ensuring that animal caretakers have access to information and program support at all steps of the process.

Similarly, participants should not be put at undue risk to meet the needs of programming. For example, it is not appropriate to expose humans who may be particularly vulnerable to infectious disease to large numbers of volunteers, especially if appropriate personal protective equipment, hand hygiene, or physical distancing is not available. Likewise, congregating large numbers of people and animals in a small space or unsafe area may increase the likelihood of anxiety or injury.

Promotional work and use of media

The use of media and public relations should be considered carefully. Promotional descriptions of these activities, as with all community work, should accurately reflect the goals and impact; for example, a program performing 20 animal surgeries per year while training students does not impact overpopulation and therefore should not be marketed as such.

Building an understanding of a program among external interested parties and the public often relies on sharing stories and experiences and can be critical to long-term operations and funding. When implemented correctly, sharing stories can also engage populations accessing services in a meaningful way and can be empowering, as noted in some storytelling efforts in groups like veterans’ groups.12 Organizations should provide care and training regardless of whether the participants are willing to be identified publicly; sometimes being identified publicly can put individuals at risk.

Consent

Informed consent should be freely given. Participants should not be required to consent to all recommendations in order to access some components of services. Programs should provide clear releases, accommodations, and communication outlets for concerns. See Chapter 6 for more discussion on research-focused informed consent.

Recordkeeping

All programs must keep complete medical records in keeping with regulatory requirements for veterinary practice, including controlled drug disposition. Medical records should be made available to owners and veterinary professionals upon request; copies of medical information and care instructions must be provided to pet owners receiving services.

Follow-up care

Accessible care services are often most needed in communities which experience barriers to urgent care and emergency services. A plan and resources should be available to help caretakers access emergency care when complications arise after wellness or spay-neuter clinics. This follow-up care is particularly important if trainees are involved in providing services, since complication rates, or the perception of increased complications, may be higher.13 Likewise, when initiatives take place outside of a clinic or hospital environment, a plan should be in place for accessing such care in the rare event it becomes necessary. There may also be legal and/or professional obligations to provide a pathway for follow-up care; regardless, there is a moral and practical obligation to do so.

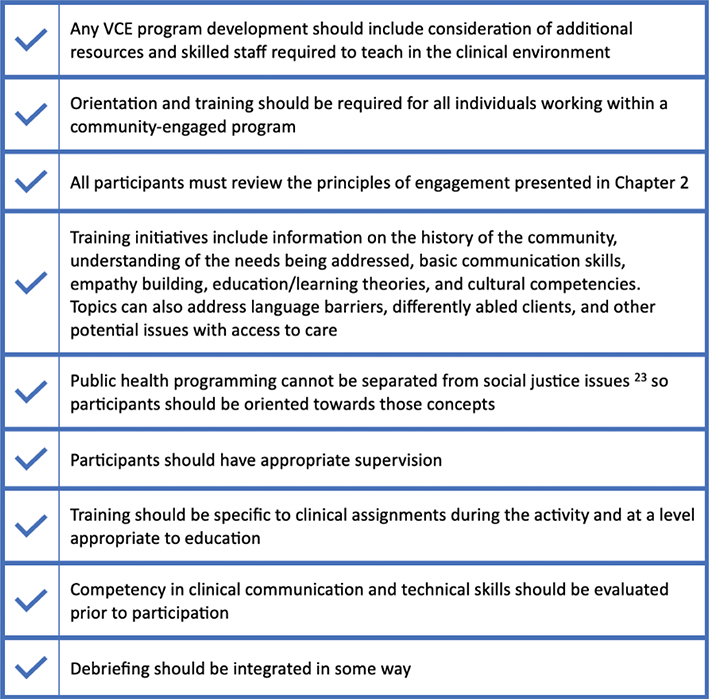

Reflection activities following events