SHORT REPORT

Veterinarian of Record Relationships for Animal Shelters: Differences in Expectations between Veterinarians and Nonveterinarian Shelter Administrators

Sara R. Almcrantz, Emily J. Walz and Terry G. Spencer*

Maples Center for Forensic Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Abstract

Veterinarian of record relationships (VoRRs) are nonregulated business agreements between animal shelters, veterinarians, and distributors that allow resource-limited organizations to purchase wholesale medical supplies. Anecdotally, animal shelters report difficulty retaining veterinarians to serve as Veterinarians of record (VoRs) and veterinarians report reluctance to work with animal shelters, resulting in increased expenses for the organizations and diminished access to veterinary care for their populations. We distributed an anonymous, online survey to explore the motivations and expectations of a VoRR from the perspective of the animal shelter administrator and the potential VoR. The primary motivators to enter a VoRR and concerns about a VoRR differed between veterinarian and nonveterinarian respondents. Specifically, veterinarians were significantly more concerned than nonveterinarian administrators about adherence to the legal requirements to fulfill a veterinary-client-patient relationship (VCPR). Additionally, veterinarians expected significantly higher compensation for veterinary services than shelter administrators expected to provide. These findings suggest a potential disconnect between shelters and veterinarians regarding financial, legal, and ethical aspects of VoRRs, possibly leading to hesitance among veterinarians to engage in such roles. Describing these differences is the first step in determining how to bridge these expectation gaps toward the joint goal of improving welfare for animals in shelter settings.

Keywords: veterinarian; animal shelter; veterinarian-client-patient-relationship; survey; motivation; goals; welfare

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2024, 3: 70 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v3.70

Copyright: © 2024 Sara R. Almcrantz et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 17 October 2023; Revised: 12 January 2024; Accepted: 11 February 2024; Published: 8 March 2024

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correspondence: Terry G. Spencer. Email: tspencer@ufl.edu

Reviewers: Sue Neal, Benjamin Butina

Supplementary material: Supplementary material for this article can be accessed here.

Nonprofit and municipal animal shelters often purchase medical supplies and pharmaceuticals from veterinary wholesale companies at a discounted price. However, with the advent of the United States Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry # 263,1 there are relatively few antimicrobials or other drugs that can be purchased without veterinary oversight and/or a prescription from a veterinarian. It is industry standard that animal shelters may open purchasing accounts with veterinary wholesalers if they retain a supervising veterinarian. In practice, this relationship may take many forms, from a veterinarian employed or contracted by the animal shelter providing all veterinary services to a volunteer community veterinarian providing minimal services beyond oversight of purchases. For this study, we define these arrangements as veterinarian of record relationships (VoRRs) and to the veterinarian who provides a copy of their license as the veterinarian of record (VoR) for the shelter.

Anecdotally, animal shelters report difficulty hiring or retaining community veterinarians to serve as VoRs and veterinarians report reluctance to work with animal shelters, likely resulting in increased expenses for the organizations and diminished access to veterinary care for their populations. The purpose of this research was to investigate the motivations of veterinarians who serve as VoRs and describe the expectations that veterinarians and animal shelters have in forming VoRRs.

Methods

The study protocol was reviewed by the University of Florida IRB-2 (#IRB202202368)

Following the CHERRIES checklist,2 a 24-question anonymous survey was created using an online platform (QualtricsXM, Provo, UT) that included branching logic, open, and close-ended questions. The question wordings were reviewed by a panel of subject matter experts who included practicing shelter veterinarians, shelter veterinary technicians, leaders of municipal and nonprofit animal shelters, and shelter consultants (see Appendix 1 for survey questions)

The online survey was distributed to a convenience sample of respondents between December 2022 and February 2023. An invitation to complete the survey was distributed to the membership of three professional veterinary organizations (Association of Shelter Veterinarians, Association for the Advancement of Animal Welfare, Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association) to the mailing list of a cooperative buying program for animal welfare organizations (Shelters United Cooperative Buying Program) and to all graduate students and faculty in the University of Florida’s Online Graduate Program in Shelter Medicine. The survey was also promoted on social media sites intended for veterinary and animal welfare professionals as well as to the attendees of an online webinar and via QR code in the exhibitor hall of a national veterinary conference (VMX Conference, January 2022, Orlando, FL). Additional snowball sampling occurred via professional networks to an unknown number of additional individuals, thus it is not possible to calculate an overall response rate.

Data collected were analyzed using SPSS (IBM, Ver. 28.0) to generate descriptive statistics. A Kruskal–Wallis chi-square approximation was used to test for relationships between cohorts of respondents relative to both continuous and ordinal-level dependent variables. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A total of 307 people completed the survey in its entirety, and an additional 126 people omitted answers to one or more questions but were included in data analysis. Respondents consisted of 61% (n = 265) nonveterinarian shelter administrators and 39% (n = 168) veterinarians.

Of the veterinarians, 59% (n = 99) reported having previously served in VoRRs, while 32% (n = 54) had served in a capacity different from the way VoRRs were defined in the survey, and 9% (n = 15) had never served as VoRs. Most of the veterinarians worked with one or more shelters (69%; n = 116) and many volunteered, consulted, or provided discounts or donated services for shelters (38%; n = 63).

Motivations and concerns about VoRRs

The top three factors that motivated veterinarians to serve as a VoR included to improve animal welfare (80%, n = 134/168), help the community (74%, n = 124/168), and provide spay/neuter services (61%, n = 102/168). The primary concerns identified by veterinarians were related to not trusting shelters to follow their veterinary advice (71%, n = 102/143) or having experienced previous VoRRs that failed (32%, n = 46/143). By comparison, the primary concerns identified by nonveterinarians were related to not being able to afford to contract/retain a VoR (75%, n = 130/174), or encountering veterinarians who are unwilling to discount their services for nonprofit organizations (75%, n = 131/174).

When asked to consider seven legal and ethical risks related to establishing and maintaining a VoRR (including stipulations for a veterinary-client-patient relationship), the veterinarians (n = 157) were significantly (p < 0.0001) more concerned about each of the legal and ethical factors than were the nonveterinarian administrator (n = 217; Table 1).

VoRR satisfaction, compensation, and duties

Veterinarians were significantly less satisfied with their current or most recent VoRRs than nonveterinarian shelter administrators (χ² = 10.4317, p = 0.0012). Whereas 69% of shelter administrators reported feeling ‘very satisfied’, only 48% of veterinarians reported feeling ‘very satisfied’ with their current or most recent VoRR. And while only 6% of the administrators reported that they ‘are not satisfied’, 11% of the veterinarians reported that they ‘are not satisfied’ with their current or most recent VoRR.

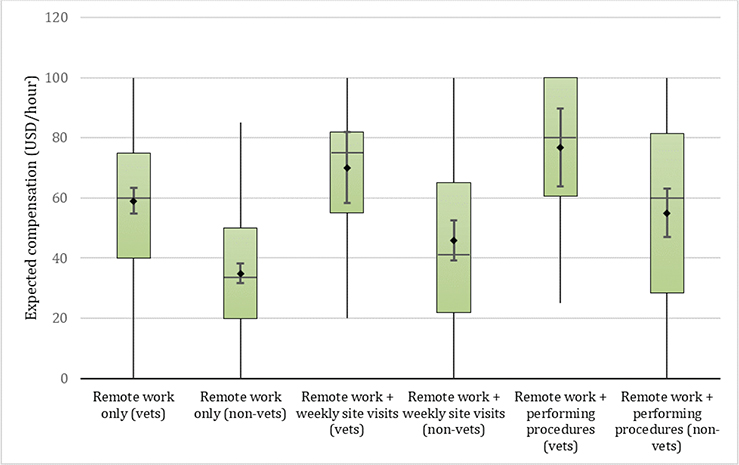

Because VoRRs span a variety of working arrangements, we asked about expectations for compensation across three possible arrangements: exclusively remotely, work remotely with weekly on-site visits/rounds, or work remotely with weekly on-site visits/rounds and performing some procedures on-site. While both veterinarians and the nonveterinarian administrators expect more compensation if the veterinarian spent more time on site at the shelter, veterinarians expected a significantly higher hourly compensation across all three work structures (p < 0.001; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expected hourly compensation for veterinarians of record among veterinarians and non-veterinarians across three possible work arrangements (includes a 95% confidence interval around the mean).

Conclusion

VoRRs are a business necessity for animal shelters intended to reduce medical expenses and allocate limited funds to save more lives. However, this study suggests that differing expectations about the financial, legal, and ethical aspects of the VoRRs might be leading to frustration and diminished trust between animal shelters and veterinarians, resulting in veterinarians’ hesitance to serve as VoR. We suggest that more work is needed to determine how to bridge these gaps to motivate more veterinarians to engage in VoRRs with their local animal shelters.

Author contributions

TS and SA conceptualized and implemented the study; EW and SA participated in developing methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and data visualization. All authors contributed to manuscript development, editing, and revision.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank James Colee for his assistance with the statistical analysis of the survey results; Mal Schwarz and Julie Bank from Shelters United for encouraging the authors to investigate this topic; Dr. Aimee Dalrymple, Dr. Becky Morrow, Dr. Jeff Fortna, Christa Nelson, and Sarah Green for reviewing the survey questions prior to distribution; and Julie Bank and Dr. Aimee Dalrymple for providing valuable feedback about drafts of this manuscript.

References

| 1. | FDA. CVM Guidance for Industry #263: Recommendations for Sponsors of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs Approved for Use in Animals to Voluntarily Bring Under Veterinary Oversight All Products That Continue to be Available Over-the-Counter | FDA. Accessed Dec 27, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/cvm-gfi-263-recommendations-sponsors-medically-important-antimicrobial-drugs-approved-use-animals |

| 2. | Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 |

*Terry G. Spencer. Email: tspencer@ufl.edu

Appendix 1. Survey questions

The following questions were posed to all survey participants: Q1, 2, 4, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 19, 22, 24, 25

The following questions were posed only to veterinarians: Q3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 17, 23

The following questions were posed only to nonveterinarians: Q6, 8, 18, 20, 21

Q1: Informed consent agreement

Q2: Are you a veterinarian? (Yes/No)

Q3: Which of the following apply to you? Select all that apply. (Work at an animal shelter or rescue organization, volunteer at an animal shelter or rescue organization, provide consultation or donated/discounted veterinary services to an animal shelter or rescue organization)

Q4: How many shelters or rescue organizations do you currently work, volunteer, and/or consult for? (0–4 or more)

Q5: Which of the following describes the types of shelter(s) or rescue(s) that you currently work at, volunteer or consult? Select all that apply. (Municipal or government operated shelter, privately owned and operated shelter, privately owned and operated with municipal contract, animal rescue, animal sanctuary, trap neuter return (TNR), I do not work, volunteer, or consult at a shelter or rescue, other).

Q6: Which of the following describes the types of shelter(s) or rescue(s) where you currently work or volunteer? (Municipal or government operated shelter, privately owned and operated shelter, privately owned and operated with municipal contract, animal rescue, animal sanctuary, trap neuter return (TNR), I do not work, volunteer, or consult at a shelter or rescue, other)

Q7: Have you ever served as a Veterinarian of Record for a shelter or animal rescue organization? ‘Veterinarian of Record’ is defined as a veterinarian that allows a shelter/rescue organization to use his/her veterinary and DEA licenses to order drugs and medical supplies and oversees their use even if not physically present. (Yes/No)

Q8: Have you/your organization ever utilized a Veterinarian of Record? (‘Veterinarian of Record’ is defined as a veterinarian that allows a shelter/rescue organization to use his/her veterinary and DEA licenses to order drugs and medical supplies and oversees their use even if not physically present). (Yes/No)

Q9: How satisfied are you with your current or most recent Veterinarian of Record relationship? (Not satisfied/somewhat satisfied/very satisfied)

Q10: What motivates you or would motivate you to serve as a Veterinarian of Record for an animal shelter/rescue organization? (Helping the community, financial benefit, animal welfare, population management, spay/neuter, clinical case variety, ability to work remotely, other)

Q11: Please rank your level of concern about each of the following ethical and legal considerations that may affect establishing a successful Veterinarian of Record relationship in a shelter/rescue setting. (Ranked on a scale of 1–3 level of concern: initiating treatment without consulting a veterinarian, adhering to state and local laws/regulations, purchasing and storing controlled drugs, drug record keeping, medical record keeping, dispensing prescriptions, establishing a veterinary client patient relationship (VCPR))

Q12: Do you have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or similar contract that you use to create a Veterinarian of Record relationship? (Yes/no/not sure)

Q13: If you are willing to share your MOU/contract to better inform our research, please attach it here (Optional file upload)

Q14: Please rank your level of concern about each of these potential roadblocks for serving as a Veterinarian of Record for a small shelter or rescue organization. (Ranked on a scale of 1–3 level of concern: I don’t know how to negotiate a MOU/contract to serve as a VOR, I don’t know what to charge for my time to serve as a VOR, I am unfamiliar with evidence-based shelter medicine for advising small shelters/rescue groups about their protocols and SOPs, I don’t have the time to advise an organization, I don’t trust small shelters/rescues to follow my veterinary advice, I have served as a VOR in the past but the relationship broke down, I don’t trust the people who work or volunteers with small shelters/rescues, I don’t know how to sustainably discount services)

Q15: Would you be willing to participate in continuing education (e.g., webinar or short course) to help you/your organization learn how to establish and maintain an effective Veterinarian of Record relationship? (Yes/no/not sure)

Q16: What would you most desire to learn during this training? Select all that apply. (Negotiating contracts/MOUs, proper compensation for veterinary work and expertise, setting boundaries and limits, evidence-based protocols and SOPs, adhering to state and federal regulations, using telehealth tools, adhering to best practice guidelines for shelters, sharing decision-making authority, maximizing efficiency, effective communication, other)

Q17: What per hour rate (in U.S. dollars) would you feel is adequate compensation for serving as a Veterinarian of Record in each of the following scenarios: working exclusively remotely, work remotely and by making weekly on-site visits/rounds, and work remotely and by making weekly on-site visits/rounds and performing some procedures on-site ($0–100 slidable scale)

Q18: What per hour rate (in U.S. dollars) would you be willing to compensate a Veterinarian of Record in each of the following scenarios: work exclusively remotely, work remotely and by making weekly on-site visits/rounds, and work remotely and by making weekly on-site visits/rounds and performing some procedures on-site ($0–100 slidable scale)

Q19: How much discount for services do you think is appropriate for treating shelter and rescue pets in a full-service veterinary practice? (100%, 75–99%, 50–74%, 25–49%, 10–24%, no discount, set a maximum dollar amount that can be spent per pet)

Q20: Please rank your level of concern about each of these potential roadblocks for finding/retaining a Veterinarian of Record for your organization (Ranked on a scale of 1–3 level of concern: cannot afford to contract/retain by MOU a VOR, do not have any local veterinarians who are knowledgeable of shelter medicine for small shelters/rescue groups, local veterinarians don’t have the time to advise our organization about sanitation, preventive veterinary care, and population management or to help us develop SOPs that our organization can follow, local veterinarians are unwilling to discount their services for our organization, local veterinarians won’t authorize us to purchase the medical supplies we desire to have for our organization, do not know how to arrange for a MOU or contract with a local veterinarian to serve as our VOR, our organization has used the services of VOR in the past, but these relationships broke down, nobody in our organization has any background in veterinary medicine)

Q21: What areas of shelter operations could your Veterinarian of Record assist you with? Select all that apply. (SOPs, consulting on medical conditions, consulting on behavioral conditions, disease outbreak management, disaster preparedness, animal cruelty investigations, review of shelter metrics, euthanasia services, spay/neuter surgery, other, none of the above)

Q22: How interested would you be in using telehealth to communicate between shelters and Veterinarians of Record? (Not interested/somewhat interested/very interested)

Q23: Which additional training would most help you establish a Veterinarian of Record relationship with a shelter/rescue? Select all that apply. (Sample MOU/contracts, sample shelter SOPs, additional training in infectious disease and outbreak management, additional training in shelter medicine and surgery standards of care, shelter euthanasia techniques, shelter behavioral assessments, cruelty animal investigations/forensic medicine, community cat management, community outreach/disaster management, other, none of the above)

Q24: Is there anything else you would like to share about your experience or concerns regarding the Veterinarian of Record relationship? (Free text)

Q25: If you are willing to participate in a pilot project to test standardized Veterinarian of Record relationships between shelters or rescues and willing veterinarians, please leave your name and contact information here. We will not connect your name with any of your responses, and you do not need to work in a shelter currently or have any shelter medicine experience to get involved. Thank you! (Optional fields for name, email, phone number, job title, and state where respondent works)