SPECIAL ARTICLE

Cat Friendly Decision-Making

Identifying solutions for ‘inbetweener’ cats

Vicky Halls and Claire Bessant

Keywords: Inbetweener cat, cat friendly, unfriendly cats, fearful cats, rescue

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2023, 2: 59 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v2.59

Copyright: © 2023 Vicky Halls and Claire Bessant. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Published: 22 August 2023

Correspondence: Vicky Halls, Email: Vicky.halls@icatcare.org

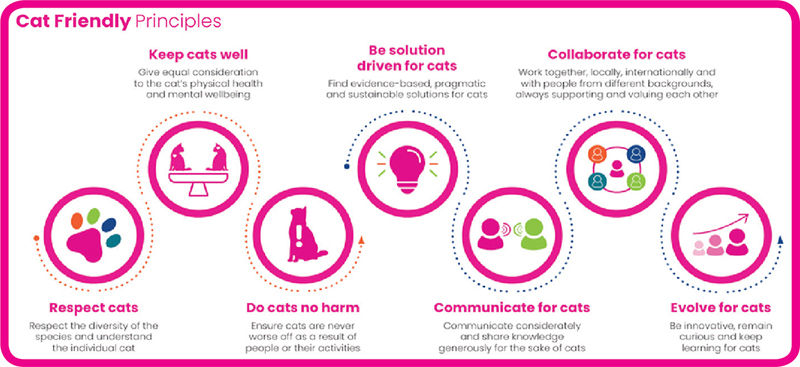

This Cat Friendly decision-making document provides information regarding the identification of a type of cat, referred to as an ‘inbetweener’. These cats have previously been kept as pets despite being unsuited to this lifestyle because they are fearful, anxious or frustrated and do not behave as owners expect them to in terms of being near people and able to be stroked. Identifying these cats will help to ensure that decisions are made that take into account their specific needs. This document recommends outcomes for these cats that include them living outdoors (or with unlimited access to outdoors in a domestic home), so the information will be relevant for those countries or regions where it is legal and acceptable for cats to live partially or fully outdoors. This information would be of interest to anyone working with, or interested in, unowned cats, including cat homing and TNR organisations, veterinarians, nurses and technicians and pet cat owners.

In this document, the words ‘cat friendly’ refer to human behaviour that is underpinned by iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles. The word ‘cat’ refers to the domestic cat species Felis catus.

International Cat Care’s (iCatCare’s) series of Cat Friendly decision-making documents are intended to be plain-speaking guides to help those working with cats to navigate complex issues and to aid decision-making where nothing is black and white. They present respectful and carefully reasoned discussions, bringing together all aspects of specific topics, including:

- Available science

- Current practice

- Diversity of challenges faced by people working with cats

- Reflection of opinions, beliefs and practices to capture and acknowledge the ‘mood’ to help assess any approach required to improve cat welfare.

They are all underpinned by iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles (see below).

Understanding the topic: Identifying solutions for inbetweener cats

Most homing organisations have cats that have been:

- Relinquished because they have developed ‘problem behaviour’ that owners find unacceptable

- Relinquished because they have failed to meet the owners’ expectations of how pet cats should behave

- Adopted and subsequently returned, as they have failed to settle, or they have not met the expectations of the new owners

- Confined in the care of the homing organisation for very long periods of time, because:

- they fail to appeal to potential adopters because they are non-responsive, hide away, are fearful and/or display aggressive behaviour and body language when approached by people1

- those caring for them are not aware of these cats’ specific needs or what solutions are available

iCatCare, through its Cat Friendly Homing (CFH) programme, has identified some of these cats as inbetweeners. These are cats that have been treated as pets (i.e. live with people as companion animals) but are unable to live without chronic fear, anxiety and/or frustration in a conventional pet setting (e.g. living with some confinement and in close proximity to people), hence the reason why so many of them are found in the care of homing organisations, often for prolonged periods. This could be because, for example:

- They did not have sufficient or the right quality of interaction with people as young kittens, so they are distressed2 in some way around people3–5

- They have a temperament trait that means they can be fearful or anxious of, and/or frustrated with, people

For these cats, just finding another conventional pet home will not be a successful solution. It is not one specific feature of a pet home (e.g. the presence of a dog or a new baby), that causes the distress. Instead, it is the very nature of a pet home, for example, confinement and close social interactions with people, that causes the cat distress. Recognising inbetweeners allows homing organisations to identify cats that have lived unsuccessfully as pets, not because the specific home wasn’t right for them, but because no conventional pet home would suit. Once cats have been identified as possible inbetweeners, homing organisations can develop and utilise an alternative plan of action and the cats can have outcomes that suit their individual needs.

The lifestyle spectrum of the cat

iCatCare defines a spectrum of cat lifestyles that are common to cats around the world, providing a structure to help in understanding cats and outcomes. Four broad types of cat exist on the spectrum – see diagram below, indicating where the inbetweener sits on this spectrum.

The spectrum is based on two key criteria:

- Whether the cat is capable of living happily with people as a pet or, at the other end of the spectrum, would be distressed living closely with people and would try to avoid them

- Whether the cat is adapted to living independently of people outdoors with no restrictions or, at the other end of the spectrum, is adapted to life in a domestic home (with or without access outside)

How to identify an inbetweener

Homing organisations first need to identify inbetweeners, and then have a plan of action so that the cats can have outcomes that suit their particular requirements. In order to do so, it is essential to have as much information as possible about the cat as an individual. Identifying a cat as an inbetweener may be straightforward, as evidenced by its background, origins and behaviour in its previous home. If this information is not available, it may also be established by observing the cat during its stay in the homing centre environment or in foster care.

Information gathering at intake into a homing centre

Background information from the previous owner is invaluable in establishing whether or not a cat is comfortable around people. These are some of the clues to look out for when owners are seeking to relinquish a cat that may suggest that the cat is an inbetweener.

Where the cat came from:

- There may be no history available on the cat’s early life as a kitten, because the cat was, for example:

- Bought without asking questions

- Adopted as somebody’s unwanted pet

- Adopted as a stray

- Adopted as a so-called ‘feral kitten’

- Where there is information available on the cat’s early life as a kitten, it may highlight, for example, that:

Behaviour at home:

The following behaviours, or comments made by the owner relinquishing the cat, could indicate that the cat is not comfortable around people:

- The cat frequently hides away from people (this is behaviour unrelated to a normal settling-in period or the cat being ill or injured)

- The cat avoids people; for example, it leaves the room when people enter or seeks out uninhabited parts of the home9

- The cat spends prolonged periods of time outdoors and only uses the home environment at certain times for access to food, water and shelter

- The cat scratches, bites, hisses or growls when touched by people

- The cat defecates or urinates in the house

- Owners may remark:

- ‘Scratches and bites when he doesn’t get what he wants’

- ‘Hates being picked up’

- ‘Friendly, on her own terms’

- ‘Doesn’t like strangers’

- ‘He is always miaowing loudly’

The cat scratches, bites, hisses or growls when touched by people

Some inbetweeners can become very frustrated at being caged. (Courtesy of Nadine Gourkow and taken from the ISFM Guide to Feline Stress and Health)

Physical health:

- There may be a history of chronic stress-related illness, for example, recurrent: eye infections, diarrhoea or blood in urine, frequent urination and/or urination outside of the litter tray

No one piece of background history will confirm identification of an inbetweener but having many indicators present would suggest the cat is not comfortable living as a conventional pet.

Information gathered during care in the homing centre

Some of the information that helps identify an inbetweener can be gleaned from observation while the cat is in the care of a homing organisation. This must be assessed with caution however, as signs of distress may be an indicator of the cat’s response to people in general, but may also be in response to the new environment or to new people. Many cats that are perfectly content pets in a domestic setting can become distressed in the unfamiliar and challenging setting of a cage or pen in a homing centre.

These are some observations that may suggest the cat is uncomfortable in the homing centre because it is an inbetweener.

Behaviour in the pen:

- The cat is only active at night (e.g. eating) when people are not around

- The pen is disrupted overnight – food and water bowls are upturned and bedding disturbed

- The cat paws at the bars or door of the cage in attempts to get out

- The cat remains very still, but is not asleep (cats can fake sleep when stressed)

- The cat is always hiding away

- The cat remains at the back of the pen

- The cat behaves aggressively towards people if they approach

Posture:

- The cat crouches with ‘hunched shoulders’ and limbs pulled inwards

- The cat’s head is lowered

- The cat’s tail is held close to its body

Body language:

- The cat’s pupils are dilated, and its eyes are wide open

- The cat’s ears are rotated or flattened

- The cat may lick its nose and swallow in an exaggerated way

When background information doesn’t match observations made in the homing centre

When there is no background information to suggest that a cat is an inbetweener, yet the cat is distressed in confinement, then placing the cat in foster care is recommended to see how it behaves in a normal domestic setting. Conversely, if there is background evidence to suggest that the cat may be an inbetweener, yet it seems relatively comfortable with people and with being confined, then it may be that there were other stressors for the cat within that particular home that negatively influenced its behaviour. In this case, finding a very different home environment may enable the cat to express its true temperament more fully.

The floor of a full-height pen that has been disrupted overnight. (Courtesy of Battersea Dogs and Cats Home)

This cat has hunched shoulders with legs pulled in close to its body and tail tucked in, suggesting it is uncomfortable with its surroundings. (Courtesy of Vicky Halls)

This cat is hiding in a bed in its den

Examples of cat postures that indicate they are fearful and not comfortable with their surroundings

Cat Friendly Solutions for inbetweeners

Once an inbetweener has been identified, there is an urgent need to provide a suitable outcome for that cat. How can this be implemented?

- Recruit and train caregivers on how to care for an inbetweener in advance so they are ready and waiting for their cat (see Appendices 1a and 1b)

- Identify inbetweeners in their existing homes and move them directly to a new environment, see below, thereby bypassing the need for cage confinement

- Provide specific advice and insight to the existing owner of an inbetweener regarding interaction with the cat that may allow it to stay in its current home

‘Alternative lifestyles’

Many inbetweeners would do well living a free-roaming lifestyle where they have food and shelter and a person to care for them from a distance. This can be done in many different environments, for example, around hotels, in stables, on farms and even in spacious gardens. This is referred to within CFH as an ‘alternative lifestyle’, but other organisations may use different terms such as ‘outlet cats’, ‘farm cats’ or ‘working/blue collar cats’ (specifically for those environments where the cat’s ability as rodent pest control is favoured). These inbetweeners require food and water, and shelter that is dry and draught-free. They need somewhere to toilet and unrestricted access outdoors (once settled). They will usually stay away from people but, if they don’t feel under pressure, some will start to feel comfortable and may even visit the caregiver’s home.

Inbetweeners can potentially be cared for by communities as well as individuals, although one or two persons would need to be made the cat’s official caregiver(s). Any person or community taking on a cat in this way would automatically become part of a wider inbetweener community of like-minded people where they can share ideas about shelters, for example, and how to recycle items to form homes for their free- roaming cats.

Eligibility for an alternative lifestyle outdoors

All cats eligible for an alternative lifestyle outdoors should be in good health, neutered, vaccinated and microchipped. Written instructions should be made available to the caregiver regarding the type of shelter required, the process of getting the cat used to its new life (when the cat will need to be confined within a building for a period of time) and ongoing care.

Not all inbetweeners will be suitable to live an alternative lifestyle outdoors. Although this is best judged on a case-by-case basis, the cats that would potentially be excluded are:

- Elderly cats, because of their susceptibility to age - related disease and mobility issues

- Cats of specific breeds:

- with very long hair that require regular maintenance from people to prevent matts because the cats cannot maintain the coat on their own, for example, Persian breed

- with no fur or sparse fur, for example, Sphynx or Devon Rex breeds

- that are brachycephalic (flat-faced) cats, for example, Persian or Exotic breeds

- Cats with a disease, condition or disability that requires ongoing handling to medicate or regular veterinary visits and/or makes maintenance of good health outdoors difficult

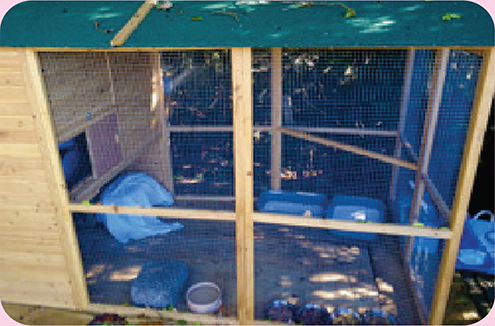

A purpose-built settling-in shelter. (Courtesy of Battersea Dogs and Cats Home)

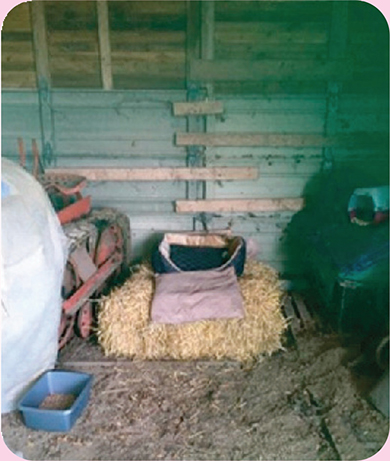

Providing hiding places in a shed

Some of these cats might be better with access outdoors with shelter but in a restricted, fenced-in area. If it is difficult for these cats to live comfortably outdoors, then euthanasia must be considered if their quality of life is sufficiently compromised.

Health care for an inbetweener with an outdoor lifestyle

Ongoing health care of the inbetweener that cannot be handled is always a challenge. Future caregivers need to appreciate that there are limitations regarding what can be done should an inbetweener become ill or suffer an injury or trauma. Some free-roaming inbetweeners may be trapped successfully (in the same kind of food- baited traps used for Trap, Neuter, Return (TNR) programmes) but treatment can only realistically take place if the condition or injury can be treated under one general anaesthetic with no further requirement for ongoing treatment that requires handling. Minor conditions may be treated by putting medication in food but if the cat requires confinement and prolonged treatment, it will be severely distressed under those circumstances and then euthanasia must be considered to prevent or alleviate suffering.

Living in a domestic home with a special caregiver

Some inbetweeners need to be near people, even living in their homes, but they don’t want regular contact or focus that is typical of a more normal owner/cat relationship. Research does show that owners who approach their cat more often for interaction actually get less contact with them.10 Allowing the cat to initiate contact can result in more interaction, as the cat is able to be in control. Inbetweeners like Smokey (see Case Study 3: Smokey), in a no-pressure situation such as this, often blossom.

It can be quite difficult to sell the benefits of caring for this kind of cat, but caregivers gain enormous satisfaction by seeing a cat thriving in a place where it feels totally in control of where it goes and what it does. Potential owners need clear instructions regarding how to behave around their inbetweener and benefit greatly from ongoing support from the homing organisation. The kind of interactive style11 required includes:

- Not approaching the cat

- Not focusing on the cat

- Giving attention only if and when the cat approaches and directly solicits it

- Maintaining strict feeding regimes at specific times of day or providing a daily dry food ration to enable the cat to eat when hungry

Initiating contact with an inbetweener can reinforce the need for it to hide or even behave aggressively

Health care for the inbetweener living in a domestic home

Inbetweeners suited to live in a domestic home with a specific kind of interaction from the caregiver, (e.g. see Case Study 3: Smokey), can be treated successfully with the support of a veterinarian who has experience in working with cats that are challenging to handle/treat.

Finding the right caregiver

It can be hard to find the special caregivers needed for inbetweeners, who are happy to give the cat everything it needs without expecting any love or gratitude in return. It may be that, once the reality is experienced, they decide there is not enough reward for them in the relationship and the cat is returned to the homing organisation. Finding suitable people in advance and establishing a network of inbetweener caregivers, who can share their experiences with each other, can be helpful. Careful recruitment of potential inbetweener caregivers and full transparency about what to expect is the key to success.

Could other cats be referred to as inbetweeners?

The use of the term inbetweener is an aid to getting the right outcome for a cat. Many cats turn up in people’s gardens, with nobody claiming to own them and are therefore considered to be strays.

Are these always stray pet cats looking for someone to take them in or could these cats be inbetweeners too? There will be occasions, based on information gleaned from local residents or even the behaviour of the cat itself, when the use of the term inbetweener to describe these cats is helpful, as it guides those caring for them towards alternative lifestyles rather than looking for pet homes. See Appendix 2 and the case of Connor to illustrate this point – sometimes cats ‘tell’ people what lifestyle they have chosen.

What if the cat has been wrongly identified as an inbetweener?

Most people are very accepting of a cat’s unexpected friendliness but, occasionally, a cat may be rejected if it has been incorrectly assessed as an inbetweener and turns out to be a loving pet that wants to live indoors. If the caregiver is unwilling to continue with the cat under these circumstances, then the cat can be returned to the homing organisation and homed as a conventional pet, based on this new piece of information about its behaviour, or be enrolled in a home-to-home adoption scheme to avoid the need to return to the homing centre.

KEY POINTS

- Inbetweeners are defined as cats that have previously lived unsuccessfully as pets, because they are uncomfortable with the close proximity of people

- Inbetweeners are usually identified when they are relinquished to homing organisations

- Inbetweeners are identified using a combination of information gleaned during intake and observations made of the cat in the care of the homing organisation

- Inbetweeners can benefit from different outcomes, for example:

- An ‘alternative lifestyle’ outdoors with shelter that is not within a domestic home

- A lifestyle in and around a domestic home with a very different kind of interaction with the owner that falls outside what is normally expected from the owner-pet cat relationship

- An alternative lifestyle would be, e.g., free-roaming where there is food and shelter and a person to provide care from a distance. This can be done in many different environments, e.g., within large gardens, hotels, stables and farms

- Alternative lifestyle environments/caregivers are best recruited in advance to enable cats identified as inbetweeners to move swiftly to their new location without spending time confined in care

- The identification of an inbetweener is not an exact science. The benefit of creating the term inbetweener is to acknowledge that not all cats are best suited for the pet lifestyle and that alternatives can and should be considered to meet the specific needs of the individual. For this to work, the general public need to be made aware of inbetweeners – indeed, once explained, many people recognise they have one or have had one in the past!

Further reading

- iCatCare website. https://icatcare.org/unowned-cats/the-different-needs-of-domestic-cats/

- iCatCare Cat Friendly decision-making: Managing cat populations based on an understanding of cat lifestyle and population dynamics. https://icatcare.org/unowned-cats/

- iCatCare Cat Friendly decision-making: Outcomes for kittens born to free-roaming unowned cats. https://icatcare.org/unowned-cats/

Need the science?

| 1. | Reisner IR, Houpt KA, Hollis NE, Quimby FW. Friendliness to humans and defensive aggression in cats: the influence of handling and paternity. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:1119–1124. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90396-4 |

| 2. | Mills D. What are stress and distress, and what emotions are involved? In: Ellis S, Sparkes A, eds. Feline stress and health: managing negative emotions to improve feline health and wellbeing. Tisbury: International Cat Care; 2016:8–17. |

| 3. | Mendl M, Harcourt R. Individuality in the domestic cat: origins, development and stability. The Domestic Cat: the biology of its behaviour. 2nd ed. Cambidge: Cambridge University Press; 2000:47–64. |

| 4. | Turner DC, Feaver J, Mendl M, Bateson P. Variation in domestic cat behaviour towards humans: a paternal effect. Anim Behav. 1986;34(6):1890–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(86)80275-5 |

| 5. | Bateson P. Behavioural development in the cat. The Domestic Cat: the biology of its behaviour. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000:9–22. |

| 6. | McCune S. The impact of paternity and early socialization on the development of cats behaviour to people and novel objects. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1995;45:109–124. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(95)00603-P |

| 7. | Barbazanges A, Piazza PV, Le Moal M, Maccari S. Maternal glucocorticoid secretion mediates long-term effects of prenatal stress. J Neurosci. 1996;16(12):3943–3949. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03943.1996 |

| 8. | Jensen P. Transgenerational epigenetic effects on animal behaviour. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2013;113(3):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2013.01.001 |

| 9. | Collard RR. Fear of strangers and play behavior in kittens with varied social experience. Child Dev. 1967;38(3):877–891. doi: 10.2307/1127265 |

| 10. | Wedl M, Bauer B, Gracey D, et al. Factors influencing the temporal patterns of dyadic behaviours and interactions between domestic cats and their owners. Behav Processes. 2011;86(1):58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.09.001 |

| 11. | Ellis LSH, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15:219–230. doi: 10.1177/1098612X1347753 |

APPENDIX 1a - template

A caregiver’s guide: Looking after an inbetweener that needs to live outdoors

[Insert cat’s name] has been assessed as an inbetweener, which is a very special kind of cat. Through no fault of his/her own [Insert cat’s name] has previously lived in an environment that doesn’t suit him/her. His/her specific needs have now been established and you have agreed to provide [insert cat’s name] with exactly what he/she needs; thank you!

[Insert cat’s name] needs a special kind of person who accepts that each cat is an individual and will care for him/her as an inbetweener with particular requirements. [Insert cat’s name] is anxious around people and this is a permanent temperament trait that is very unlikely to change.

[Insert cat’s name] requires understanding and empathy and, on a practical level, the right kind of environment and care to meet his/her needs.

Below you will find some guidance on how you can prepare for [Insert cat’s name]’s arrival and care for him/her in the longer-term. Your contact for any queries is [insert homing organisation contact details].

What is an ‘alternative lifestyle’

Environment

Some inbetweeners can live successfully in outdoor environments, providing someone is relatively close by to watch from a distance to monitor health and general condition. These environments include, for example, a large garden in a domestic home, a smallholding or farm, a stable yard, grounds to a hotel, etc.

Your inbetweener [Insert cat’s name] will require a shelter to escape from extremes of weather. This shelter can take the form of an adapted building already present, such as a garden shed or outbuilding or can be purpose-built. Placing a small shelter inside the outbuilding where the cat can sleep may provide additional warmth in colder conditions.

Settling in period

[Insert cat’s name] needs to be confined temporarily during his/her settling in period so that he/she gets used to the new territory (usually between 1 and 3 weeks depending on the circumstances). During this time, it is important to provide litter facilities (litter tray) and food and water, as far apart as possible, within a secure structure, for example, a shed, together with somewhere to sleep and several options of hiding places. Ideally, all these resources should be placed away from the door to enable safe entry to clean trays and provide fresh food and water without risking the cat being near the door on entry and subsequently escaping.

General care once [Insert cat’s name], is let out:

[Insert cat’s name], like any other cat, requires food and water and somewhere to toilet. This can be inside the designated shelter or close by. Once [Insert cat’s name] is able to be let out to roam freely, suitable areas of soil can be prepared as a toilet and a litter tray is no longer required. Feeding dry food daily may be preferable to wet food, to prevent spoiling and attracting flies. Fresh water should be provided daily. If possible, these resources should be located in an area where other animals are unlikely to access them.

[Insert cat’s name] may be less visible than a typical pet cat, and there may be days when he/she is not seen at all. Keeping a diary of sightings and observations about food eaten or disturbed bedding can be helpful in case there are any future concerns about [Insert cat’s name]’s whereabouts.

Interaction

[Insert cat’s name] does not require attention, such as eye contact, approaching, touching/stroking, from caregivers, as many inbetweeners find this threatening. However, if [Insert cat’s name] feels comfortable, he/she may approach you and appear friendly. Any response from you should be minimal, always giving [Insert cat’s name] the choice to continue to interact or to walk away. It is common for inbetweeners to live perfectly content lives without direct interaction with people.

Health care

Any concerns about his/her health, for example, sickness or injury, should be reported to [the homing organisation] for advice on further action. Any medication can be provided in food, but it is best to mix with a treat food to administer to avoid [Insert cat’s name] becoming averse to his/her normal food if something is added to it.

Ongoing health care of the inbetweener that cannot be handled is always a challenge. [The homing organisation] will support you to appreciate that there are limitations regarding what can be done should [insert cat’s name] become ill or suffer an injury or trauma. Some free-roaming inbetweeners may be trapped successfully (in the same kind of food-baited traps used for TNR programmes) but treatment can only realistically take place if the condition or injury can be treated under one general anaesthetic with no further requirement for ongoing treatment or medication that requires handling. Minor conditions may be treated by putting medication in food but if [insert cat’s name] requires confinement and prolonged treatment, and will be severely distressed under those circumstances, then euthanasia must be considered to prevent or alleviate suffering.

APPENDIX 1b - template

A caregiver’s guide: Looking after an inbetweener that needs to live in the home with a special caregiver

[Insert cat’s name] has been assessed as an inbetweener, which is a very special kind of cat. Through no fault of his/her own [Insert cat’s name] has previously lived in an environment that doesn’t suit him/her. His/her specific needs have now been established and you have agreed to provide [insert cat’s name] with exactly what he/she needs; thank you!

[Insert cat’s name] needs a special kind of person who accepts that each cat is an individual and will care for him/her as an inbetweener with particular requirements.

[Insert cat’s name] is anxious around, and/or frustrated easily by, people and this is a permanent trait that won’t change. [Insert cat’s name] requires understanding and empathy and, on a practical level, the right kind of environment and care to meet his/her needs.

Below you will find some guidance on how you can prepare for [Insert cat’s name]’s arrival and care for him/her in the longer-term. Your contact for any queries is [insert the homing organisation contact details].

Environment

[Insert cat’s name] can live successfully in a normal domestic home providing, once settled, he/she has (ideally) unrestricted access outdoors. Your home should be sufficiently large for [Insert cat’s name] to choose to be out of sight of you and other people and not to be disturbed constantly by movement around the home. There should be plenty of places where [Insert cat’s name] can hide, both on ground level and in raised places such as the top of a cupboard. The internal environment should fulfil the needs of any cat, i.e., contain the necessary resources in the right locations; [Insert homing organisation details] will provide you with information regarding what cats need in the home to be happy and healthy.

Settling in period

[Insert cat’s name] should be confined within the home during his/her settling in period – (suggesting between 1 and 3 weeks depending on the circumstances). [Insert homing organisation] suggest a single room initially, with all [Insert cat’s name]’s resources – food, water, litter tray, bed, hiding places, etc., provided as far apart as possible but all easily accessible. Ideally, all these resources should be placed away from the door to enable safe entry to clean trays and provide fresh food and water without risking [Insert cat’s name] being near the door on entry and subsequently escaping. When entering the room initially [Insert cat’s name] should be ignored unless he/she makes a specific calm and/or friendly approach for attention. Any response from you should be minimal, always allowing [Insert cat’s name] the choice to continue to interact or to walk away. [Insert cat’s name] may become frustrated at being confined in a single room and may vocalise, pace or become aggressive when you enter the room. In these cases, please let us know, but this is usually resolved by allowing [Insert cat’s name] more access to other areas of the home.

General care

Food and water should be provided twice a day, or a daily ration provided for [Insert cat’s name] to choose when to eat. A litter tray should be provided indoors, even if [Insert cat’s name] stops using it once he/she has access outdoors, to cater for those times when [Insert cat’s name] does not want to go out, for example due to weather or the presence of a strange cat.

Once allowed outside after the settling in period, access should be provided, ideally, with no restrictions. The best way to provide this is to fit an entry system cat flap to a convenient wall or door which reads [Insert cat’s name]’s microchip on the back of his/her neck and allows him/her only to enter your home. If it is not possible to fit such a cat flap, or [insert cat’s name] is reluctant to use it, then an open door or window would suffice but this is difficult to manage at night and when you are out of the house.

Interaction

Interaction should always be initiated by [Insert cat’s name]. Inbetweeners benefit from being largely ignored unless they actively seek attention! [Insert homing organisation contact] will give explicit instructions regarding interaction that are tailored for his/her individual needs.

Health care

[Insert cat’s name] can be treated successfully with the support of a veterinarian who has experience in working with cats that are challenging to handle/treat. Always speak to your veterinarian in advance to ensure that they understand [Insert cat’s name] his/her special requirements.

APPENDIX 2

CASE STUDIES

Case Study 1: Peppa needed an outdoor lifestyle

Peppa (left) at the breeder’s home in the pen with the male cat

Peppa, a 5-month-old Bengal, was purchased from a breeder where she had been housed in a pen with a male with plans to breed from her, but she had proved too ‘shy’. Peppa’s new owner realised that her new cat was not behaving as expected. She sought guidance from a pet behaviourist and it became clear that Peppa had not had the necessary early experiences needed to live comfortably as a pet in a home environment, and needed an outdoor home. Arrangements were made via Battersea Dogs and Cats Home for Peppa to become part of their ‘Outlet’ scheme, where ‘inbetweeners’ were placed in ‘alternative lifestyles’. A farm home was found and a volunteer for Battersea built her a shelter, another small den and a secure area to keep geese and other livestock out. Once settled, she would be free to roam throughout the whole farm.

The farmer reported on a later follow-up that Peppa was comfortable and confident and had not hidden away when approached at feeding times. She remained present with him there, and eager for her food (he has not attempted to stroke her and accepts he shouldn’t).

Peppa’s den at the farm

Case study 2: Connor needed an outdoor lifestyle

Connor was thought to be a stray as some local residents reported that he had been abandoned when a family had left the area. He was fighting pet cats and stealing food. Nobody claimed ownership of him.

A homing organisation agreed to take him into a pen in the garden of one of their volunteers. Connor seemed very frightened and he spent most of his time high up on a shelf, ears always flat to his head and wide eyed. When the volunteer went into his pen to feed him or clean his litter tray, he would lash out at her. She could not touch him. He would only eat in his pen when she wasn’t there.

With the lack of background information and the suspicion that he had been a pet, they wondered whether the reason he had been abandoned was that he hadn’t been socialised appropriately as a kitten. The homing organisation felt it was reasonable to categorise Connor as an inbetweener, reliant on humans to feed him but incapable of living a conventional pet lifestyle.

Although Connor was quite long-haired, he was keeping his coat free of matts so he was considered a suitable candidate for a free-roaming lifestyle. The team wrote a profile for Connor on their social media page, asking for a home on a farm or in a stable yard. A couple came forward who had no other cats and a large secure barn where there were few people. Connor could acclimatise to the new surroundings in peace.

Connor did not like to be approached

CCTV cameras were installed in the barn and he was observed grooming, exploring and eating well. He actually escaped from the barn after several days but returned to use it as his base for a free-roaming lifestyle with continued support.

New barn enclosure

Facilities provided in the barn

Case study 3: Smokey needed to live in a home with a special caregiver

In her previous life, Smokey had lived in a cage in her owner’s living room for 18 months ‘to keep her safe’, as she had been mishandled and injured as a kitten by the three children in the household. A relative visited and was alarmed to see Smokey’s situation, so she immediately contacted her local homing centre and told them the story. They arranged to visit the owner to see how they might help. After a tearful discussion, Smokey’s owner agreed to give the cat up for adoption to find a home that would enable her to live freely again.

Smokey appeared very scared of people and proved challenging to care for in the homing centre. She hid and if anyone came near, she launched an attack. The staff believed, based on Smokey’s history, that she had come from a pet cat mother and may have been well socialised with people in the breeder’s home, but her experiences after that may have affected her. They knew that Smokey needed a different environment for them to fully understand the long-term implications of these experiences. They decided to put her into the foster care of someone with experience, and the necessary training, to give Smokey the kind of hands-off care she needed.

They had to be sure that Smokey was capable of adjusting to be a happy and safe family pet. If this wasn’t going to be the case, foster care would at least establish more accurately what could be done for her.

The foster carer, Kim, gave Smokey the time to adjust at her own pace. Kim made no attempts to interact with Smokey, allowing her to explore one room and then, in her own time, the rest of the house. Smokey ambushed Kim and her husband frequently, grabbing at their feet and ankles. She was full of explosive excitement 1 min and acute fear the next. She liked living in a home environment but didn’t feel safe around people. It was agreed that Smokey was an inbetweener.

Smokey continued to thrive in her new temporary home and her life transformed when she discovered Kim’s garden – she was eager to explore outdoors and, when inside the home, she was more relaxed around Kim and her husband. Kim decided to keep Smokey and she continues to flourish. However, years later, she still needs the same hands-off approach and, if she ever does want more interaction, it will be on her own terms and in her own time!

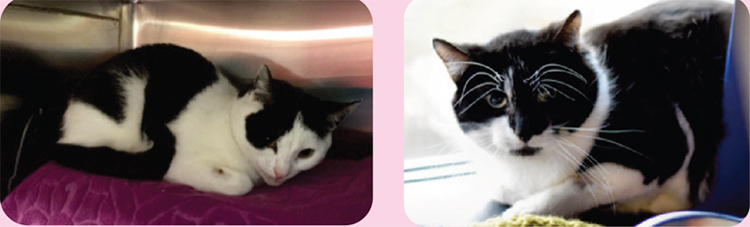

Smokey fearful and hiding at the homing centre

Smokey relaxed and enjoying life in her new home