SPECIAL ARTICLE

Cat Friendly Decision-Making

Managing cat populations based on an understanding of cat lifestyle and population dynamics

Vicky Halls and Claire Bessant

International Cat Care, Place Farm, Tisbury, Wiltshire, United Kingdom

Keywords: Cat population, TNR, street, community cat, feral, stray, cat friendly

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2023, 2: 58 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v2.58

Copyright: © 2023 Vicky Halls and Claire Bessant. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Published: 22 August 2023

Correspondence: Vicky Halls, Email: Vicky.halls@icatcare.org

This Cat Friendly decision-making document on managing cat populations, based on an understanding of cat lifestyle and population dynamics, introduces the idea that cat population management should be based on an understanding of cats, people, culture and the issues that arise when cats and people come together. Moreover, learning from good outcomes in one population management situation can be used in others, thus reducing practices that result in poor cat welfare. This document has been written for cat welfare organisations, local, regional and national governments and individuals with an interest in cat population management.

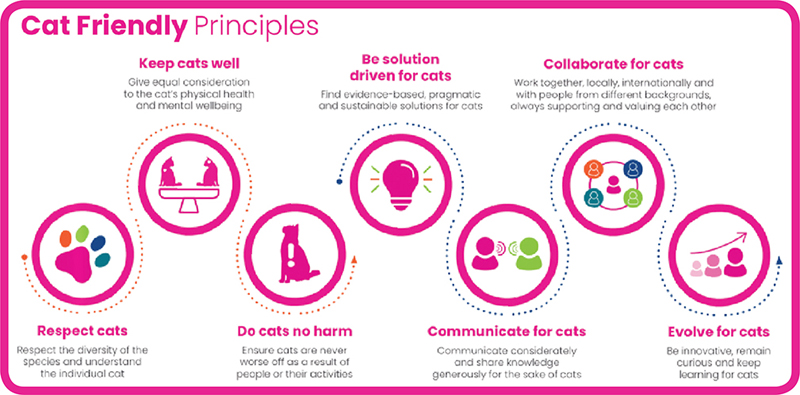

In this document, the words ‘cat friendly’ refer to human behaviour that is underpinned by iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles. The word ‘cat’ refers to the domestic cat species Felis catus.

International Cat Care’s (iCatCare’s) series of Cat Friendly decision-making documents are intended to be plain-speaking guides to help those working with cats to navigate complex issues and to aid decision-making where nothing is black and white. They present respectful and carefully reasoned discussions bringing together:

- Available science

- Current practice

- Diversity of challenges faced by people working with cats

- Reflection of opinions, beliefs and practices to capture and acknowledge the ‘mood’ to help assess any approach required to improve cat welfare.

They are all underpinned by iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles (see below).

Understanding the topic: Cat populations and current management strategies

Although precise numbers are unknown, there are estimated to be as many as 600 million cats worldwide,1 more than half of which are unowned. This document focuses on unowned cats. Definitions of owned and unowned are as follows:

Owned

- Supported by people as pets in homes, either confined with no outdoor access, or given free or limited access (by physical space or time) to the outdoors.

Unowned

- Living outdoors, free-roaming either within the human community and dependent on people to a degree for survival, or outside areas of human habitation where they are self-reliant

- Confined in homing centres (also known as shelters, sanctuaries, rescue centres or adoption centres) or in foster care awaiting adoption

It is important to recognise, when considering the definition of unowned cats as stated above, that:

- In some cultures, cats that iCatCare defines as unowned may be considered owned to some extent by members of the community2

- Some cats living temporarily outdoors may be owned pet cats that have strayed

- In some countries non-governmental organisations/charities take on a form of legal ownership when the cats are in their care

Interplay between cats and people

Cats living outdoors but within the human community can have a positive and/or negative effect on people’s lives. The interplay between cats and people can give rise to strong emotions and opinions both in support of, and against, cats.

- If there are sufficient resources (e.g. food and shelter) for the cats, and no conflict with people, pets or wildlife, then cats may not be viewed as a problem

- Issues, such as high disease prevalence among the cats, and conflict with pet cats and people, tend to become a problem when numbers are higher and resources can no longer support the unowned cats. This can impact individuals and the human community in different ways:

- Public health worries about disease or hygiene problems

- Nuisance caused by noise/smell/waste

- Concerns over disturbance to wildlife/vulnerable species/ecosystems

- Distress for people caused by seeing cats that are suffering

- Distress for people caused by seeing inhumane population management actions (e.g. culling by poisoning) which also causes cats to suffer

- Overwhelming of staff and volunteer capacity and resources in homing organisations, resulting in many cats being euthanased

Many of these issues can exist regardless of the number of cats, but are less obvious when cat numbers are low and tend to lead to action when the numbers rise. An understanding of the problems in context, and how management of cat populations can solve them or reduce their impact, is essential.

Reasons why cat numbers increase and decrease

Cat numbers increase because:

- Unneutered free-roaming cats reproduce rapidly. Feeding of these cats by people makes them healthy enough to breed more successfully and increases the likelihood of their kittens surviving to adulthood

- Previously owned cats join the unowned free-roaming cat population:

- Owners may not neuter pet cats before they reach reproductive age and abandon pregnant cats or kittens

- Owners may abandon unwanted pet cats

- Cats move in from other locations, attracted by the presence of food

Cat numbers decrease because of:

- Disease, which increases with rising cat density

- Malnutrition, if food resources are outgrown, both the number of kittens born and the number that survive to reproduce are reduced

- Accident/trauma

- Persecution by those who dislike cats

- Neutering, which prevents kittens being born

- Culling of cats, which will temporarily decrease numbers (see page 4)

Because people provide food, and cats are adaptable and able to reproduce even in tough situations, populations generally grow rather than reduce, leading to the problems outlined above. Therefore, there is a need for people to take responsibility to control populations of cats. This can be done well, in an organised, humane and even cat friendly way. However, it is often done in a reactive way that does not take into account the complexities of the situation and may be ineffective, wasting money, as well as causing suffering and distress for the cats.

Methods of controlling the number of unowned cats

Successful population management aims to treat cats humanely and address the issues that are of concern to people. The goal is to maintain population numbers at a level where resources are sufficient and human tolerance for cats is high, and below the level where cats suffer and become a nuisance for people. This can be achieved through a combination of neutering, prevention of abandonment of pet cats and finding homes for friendly cats. Some methods are humane (and often most effective when used in combination) while others are not humane, but all are listed below.

Neutering

Controlling reproduction by neutering is vital in both owned and unowned cat populations. Here we refer to neutering as surgical removal of both male (castration) and female (spaying) reproductive organs by veterinary intervention; other words used include sterilised, altered or desexed. This is currently the only method for guaranteed prevention of reproduction, although this may change in the future with the work being done by the Alliance for Contraception in Cats and Dogs (ACC&D) among others. Neutering helps to reduce cat deaths, both in the present (removing risks associated with reproduction and competition) and in the future (preventing kittens from being born and dying).3

Neutering of pet cats

The potential capacity of all cats, including pet cats, to add to population numbers should be considered, together with an understanding of the negative consequences if pets are not neutered. Owners should ideally neuter their cats prior to the time when they are capable of reproduction, at around 4 months of age.4–6 In order to achieve this, pet cat owners need to:

- Be able to afford neutering services

- Have easy access, including transport, to cat neutering services in local veterinary clinics

- Understand the benefits of neutering cats to themselves, their pets and the wider community

Unfortunately, in many countries, neutering is difficult, if not impossible, because of a lack of money and/or access to suitably qualified veterinarians to carry out the procedure or due to religious/cultural beliefs.

Neutering of unowned cats

Many cats that live outdoors cannot simply be picked up and taken to a vet for neutering. They avoid people and require a humane method by which they can be caught. ‘Trap, Neuter, Return’ (TNR) of such cats involves trapping them using a humane trap baited with food and taking them to a veterinary clinic where they are neutered. It is recommended that the tip of the left ear is removed surgically at the same time as they are under general anaesthetic to aid future identification and prevent further trapping. Once recovered from the surgery, the cat (as a territorial species) is returned to the place where it was trapped. Cats should spend the minimum amount of time in confinement, ideally only that required for the neutering surgery and recovery.

(For more information on TNR, visit the International Cat Care website: icatcare.org/unowned-cats/feral-street- cats/trap-neuter-return/)

All cats and kittens in homing centres should be neutered before they go to new homes.

Preventing abandonment of pet cats and kittens

Many cats start life as pet cats, but owners decide they do not want to keep them because of problems that arise. Abandonment of such cats could be minimised by:

- Ensuring breeders (of pedigree or non-pedigree cats) know how to give kittens the right early-life experiences to enable them to be comfortable around people and other animals, so that they fulfil owner expectations of how a pet cat behaves and are not rejected

- Helping potential owners to understand how to acquire suitable kittens and cats

- Provide information about what constitutes a kitten suitable to be a pet cat, where people should look and what questions to ask7

- Encourage potential owners to take on previously owned cats that are comfortable being pets

- Match cats and owners appropriately, as not all homes suit all cats and vice versa

- Educating owners about cat reproductive behaviour and encouraging neutering to remove reproductive potential and associated behaviours which often lead to abandonment of cats (and subsequent kittens)

- Ensuring owners have realistic expectations of the responsibilities and costs associated with pet ownership, for example, veterinary fees

- Educating owners about the cat as a species, with an understanding that cats’ needs differ from those of people8

- Giving owners access to behavioural support/interventions – guidance and general support regarding ‘problem’ cat behaviour should be widely available to avoid abandonment or unnecessary relinquishment

- Providing support and guidance for owners at times of crisis to enable them to keep their cats

Removing unowned cats to homing centres and into homes

Cats are often removed from the streets into homing centres or foster care with the aim of subsequently placing them in homes. If the process is run well, and where homes are available, many cats can find suitable new homes (see Cat Friendly Homing principles on page 8). However, a lack of suitable homes can mean that cats enter the system but cannot leave as there is nowhere for them to go. There can also be other related problems:

- Homing centres are only viable in places where people are open to acquiring ‘rescued’ or previously owned cats. Otherwise, the homing centres will simply fill up with cats and reach a point where they cannot take in any more

- Taking in cats which are unsuitable to live as pets (see The Lifestyle spectrum of the cat on p 5), without understanding the different kind of outcome they require, will lead to poor welfare as they either remain in confinement indefinitely or are adopted and swiftly returned

- Confinement in homing centres, particularly for extended periods, can compromise the physical health and mental wellbeing of cats. Stress levels experienced by cats confined in unfamiliar small spaces are high, and this stress, in combination with the inevitable overcrowding, leads to infectious disease outbreaks,9–11 particularly if disease control procedures are not good

- Some homing centres have the potential to become ‘dumping grounds’ for municipalities or local authorities, or hoarding situations may develop where large numbers of cats are accumulated without the prospect of being homed. Those caring for the cats can fail to provide minimum standards of care or act in response to the deteriorating condition of the animals and their environment. Even with the best care, cats living together in high numbers will struggle to cope

Removal by culling

In some countries, culling is used to reduce cat numbers. This includes causing death by poisoning and other means, all of which involve the cat experiencing suffering through fear and pain. There are still many places where cats are seen as ‘pests’ and labelling the species as such encourages authorities to eradicate them by any means.

Culling may be viewed by authorities as offering a rapid, one-off solution for reducing numbers. However, it is not as simple as it seems:

- Some methods of culling, such as poisoning, may pose threats to wildlife, other pets and public health risks, particularly for children

- Experience of population management of street dogs has shown that culling is not as effective in the long term as neutering programmes at reducing population size because it does not take into account the inflow of new animals. Rapid replacement rates have been documented in some areas following culling12

- Culling often meets public resistance, especially as the methods employed are frequently inhumane

Another common rationale for culling is the belief that cats are responsible for destruction of indigenous and endangered wildlife. It is argued that TNR on its own would not be an effective solution, as the cats would remain in the environment and the problem often exists in uninhabited areas where the population of cats is at a low density, making it challenging to trap them. The impact of cat predation on wildlife is beyond the scope of this document, but there are aspects to consider:

- How we value different species and prioritise the needs of one over another

- The importance of good scientific evidence regarding the role of cats and other non-endemic species in endangered wildlife predation

- Whether cats are keeping down the numbers of other animals (e.g. rats) which may also predate on endangered species13

- Other challenges to wildlife in general beyond cats, including habitat loss, use of pesticides, etc

- The actions of people trying to save these cats from being culled, which may result in them being taken into care and likely suffering as a result because they are not used to people

Removal by relocation

Another method intended to reduce cat numbers in areas where cats are unwanted or considered ‘pests’ is to relocate them as part of a TNR programme; in other words, rather than return them to their original location, the cats are relocated elsewhere.

Relocation may be appropriate in situations, for example, where the original site is no longer viable to sustain a cat population, where cats are no longer safe, or where there are concerns over predation of endangered wildlife. Given the territorial nature of cats, however, relocation needs to be carefully considered as a population management tool. Mass relocation to a single, suitable and safe site is often untenable and, therefore, a number of alternative similar sites need to be found for the placement of smaller groups.

Relocation to sites where cats are unlikely to survive – for example, an unpopulated desert area – should be seen as another form of inhumane culling, where cats are left to experience a slow death.

Homing to other countries

One growing trend is to move cats to other countries or regions with a view to finding pet homes for them because there is a demand or outlet there for cats ‘rescued’ from difficult situations.

However, there are a number of challenges associated with this:

- Stress associated with long distance travel for cats

- Demands associated with living closely with people in their homes which the individual cat cannot meet (if the animal concerned is not assessed correctly as a suitable pet)

- Restricted access outdoors if the cat has been used to free-roaming

- Adapting to a different climate

- Bringing novel parasites and diseases to the new population, including potential zoonoses (diseases that can be passed from animals to people)14

As a consequence of the many difficulties that homing to other countries can present, there is significant potential for poor cat welfare and the spread of disease. These homing decisions need to be made with care, taking into account the suitability of the cat, the health consequences for people and cats, and the future home environment. Also, outcomes need to be monitored in the long term to ensure cats adjust and remain well, and a plan needs to be in place for what to do when cats do not settle.

Finding Cat Friendly Solutions for population management

So far in this document, the cat population has been considered as a whole. However, what is clear is that it is made up of a diverse range of cats, with different lifestyles and different responses to people, an understanding of which is vital to cat welfare and effective results. Making effective, welfare-focused decisions for cats requires an understanding of their lifestyles, and how they live and interact with people.

Only then can appropriate solutions be identified for the individual cat to maximise welfare within population management.

Each solution will also need to take into account broader human community considerations, such as:

- The community’s values, beliefs and priorities

- Resources available for cat welfare, for example, financial/veterinary/facilities/staff/volunteers

- Environmental or conservation concerns

Solutions need to be understood and actioned by the people involved with the cats, either as owners or caregivers. There may also be a requirement for legal frameworks to allow people to work effectively to minimise problems caused by cats within a community. Cat Friendly Solutions are achievable where there are available funds, collaboration at all levels and access to veterinary care. There are many countries throughout the world where, as a result of complex and multiple factors, there is less desire or capacity to implement population management strategies that prioritise the welfare of cats.

In finding solutions which are effective and humane, there are two steps:

- Step 1: Understanding the lifestyle spectrum of the cat and how different cats are living and interacting

- Step 2: Matching population management solutions and individual outcomes to the lifestyles to which cats are adapted

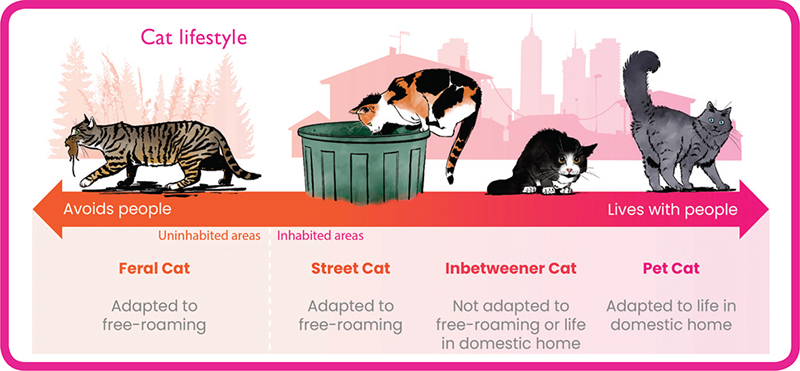

Step 1: Understanding the lifestyle spectrum of the cat and how different cats are living and interacting

There is often confusion in the way in which cats are described, with different countries, organisations, individuals and cultures using the same words to mean different things or using different words to mean the same thing!

This document suggests descriptions for cats that can be used to understand where they sit on a lifestyle spectrum, based on two key criteria:

- Whether the cat is capable of living happily with people as a pet or, at the other end of the spectrum, would be distressed living closely with people and would try to avoid them

- Whether the cat is adapted to living independently of people outdoors with no restrictions or, at the other end of the spectrum, is adapted to life in a person’s home (with or without access outside)

The aim is to be clear and consistent. Decision-making regarding the best solutions for cats, people and the organisations that are trying to help them, requires full understanding of the needs of the cats being referred to. For example, the word ‘feral’ is commonly used for all cats that are not kept as pet cats but also for cats that have little or no interaction with people. Likewise, confusion can arise because the word ‘stray’ is used interchangeably for both lost pet cats, and for cats born outdoors with no experience of living with people as pets. The solutions appropriate to cats with these backgrounds can be very different (see below).

Lifestyle spectrum

iCatCare defines a spectrum of cat lifestyles which are common to cats around the world, providing a structure to help in understanding cats and outcomes. The names may be different in different places, but the cats’ needs are universal. Four broad types of cat exist on the spectrum – feral cat, street cat, inbetweener cat and pet cat – see the cat lifestyle spectrum diagram on page 5.

Feral cats

These can be described as:

- Born and living outdoors and likely to have come from generations of feral cats

- Living independently of people at a relatively low population density in uninhabited areas

- Likely to be living a solitary lifestyle, hunting for survival

- Not socialised with people, with no experience of living in a domestic home

- Likely to be greatly distressed by confinement, including living in people’s homes

Feral cats are unlikely to cause problems within cities, towns and villages because they are not usually seen where there are people. However, they may be of concern to people if they are considered to be a threat to wildlife in uninhabited areas.

Street cats

These can be described as:

- Born and living outdoors (parents could be street cats or pet cats)

- Free-roaming at a relatively high population density in inhabited areas, for example, in cities, towns and villages

- Usually gathering with other cats around a plentiful food source (provided by people and/or scavenged from waste bins)

- Showing some tolerance towards familiar people and may even appear friendly

- Breeding prolifically and, in some locations where there are plentiful localised resources, forming a group with other cats

- Not socialised with people as kittens, with no experience of living in a domestic home

- Likely to be greatly distressed by confinement, including living in people’s homes

Pet cats

These can be described as:

- Living with people as companions, either exclusively indoors or with free access or limited access outdoors

- Socialised with people as kittens

- Coping well (ideally) with contact and interaction with familiar and unfamiliar people

A pet cat is an owned cat, but this may change to unowned if it becomes:

- Relinquished – the cat is given up for adoption to a homing centre

- Stray – the cat wanders away from home and does not return

- Abandoned – the cat is intentionally left somewhere or rejected by the owner with a view to no longer taking responsibility for it

Stray cats and abandoned cats may join the mix of free-roaming cats which live outdoors, or may appear in a back garden or yard to take up residence with someone else (thereby becoming an owned pet cat again). They are also found in homing centres and/or foster networks awaiting adoption along with relinquished cats.

Inbetweener cats

These are a type of cat, recognised and named by iCatCare as an ‘inbetweener’. The inbetweener is not usually identified until it comes to the attention of a homing centre or foster network. An inbetweener is:

- A cat that has previously lived as a pet, but unsuccessfully, because it is uncomfortable with the close proximity of people. This could be because:

- It did not have the right quality or quantity of interaction with people as a young kitten, so it is distressed around people

- It has a temperament trait that means it can be fearful or anxious of, or frustrated by, people

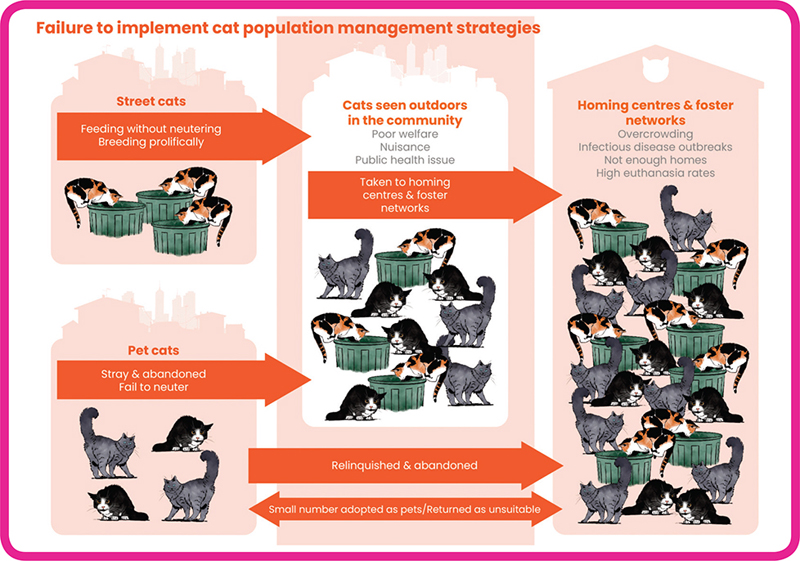

Mix of cats seen outdoors

Cats seen outdoors within a human community usually consist of neutered or unneutered:

- Street cats

- Abandoned and stray pet cats

- Pet cats that are currently owned, if they have outdoor access

Despite the common usage of the word ‘feral’, true feral cats have not been included in the mix of cats seen outdoors as they are rarely seen in inhabited areas.

Occasionally, feral cats can encroach on human habitations seeking food; this may be particularly relevant on small islands.

Failure to recognise this mix of cats seen outdoors can give rise to problems, as cats are not being considered as individuals regarding their future needs. For example, stray or abandoned pet cats could re-adapt to living with people, but homing as pets is not applicable for all cats seen outdoors (albeit, in some places, street cats seem to be more genetically tolerant of people). This misunderstanding may lead to well-meaning interventions that put street cats into homing centres, without any concrete plan once it becomes obvious that they are not going to be suitable as pets. Equally, cats may be taken off the street without consultation with local citizens, yet they are considered to be ‘owned’ by the community.

The diagram on page 7 shows how the populations are interrelated and how they impact on each other in a worst-case scenario where there are no population management solutions in place.

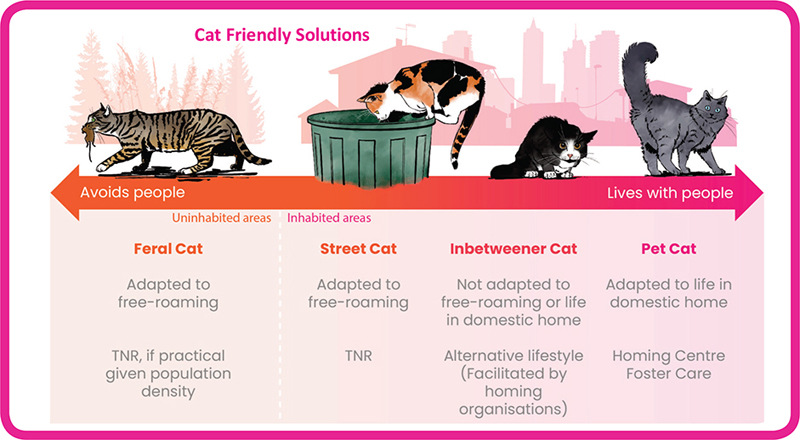

Step 2: Matching population management solutions to the lifestyles to which cats are adapted

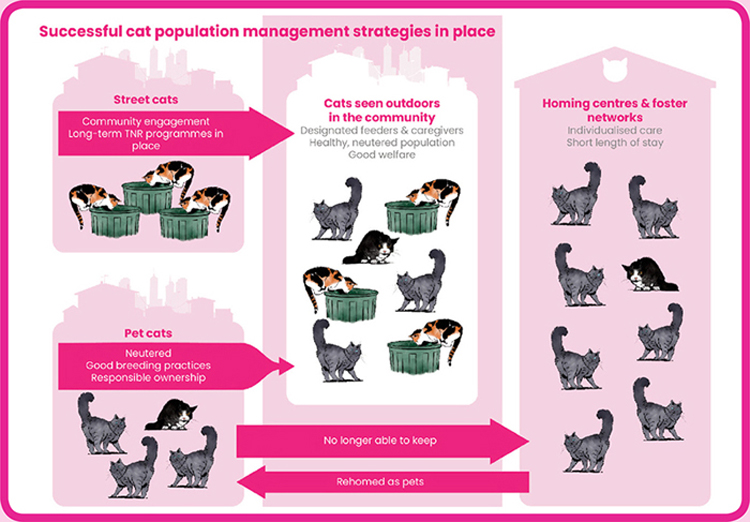

The diagram below shows humane Cat Friendly Solutions relevant to the different types of unowned cats. The aim is to improve success in controlling numbers as well as providing good cat welfare.

Feral cat solution: TNR where feasible

Ferals, unlike all other cats on the lifestyle spectrum (street, pet, inbetweener) are not reliant on people directly or indirectly for food or shelter, but rather hunt and survive on their own. They live in uninhabited areas and are typically found at least 2–3 km from the nearest human habitation. Population densities of feral cats varies and are largely dependent on the availability of prey species. Feral cats become a conservation issue when they are viewed as invasive and a threat to native species that have no evolutionary response to mammalian predators and are therefore particularly vulnerable. The problem is that TNR does not remove their ability to predate on wildlife, as discussed previously in this document on page 3. TNR may be appropriate in some individual cases, but the management of feral cats in sensitive areas is a contentious issue with strong opposing opinions and the culling methods used to reduce numbers would rarely be seen as humane. Each case and specific situation needs to be considered carefully and pragmatic, humane solutions explored.

Street cat solution: TNR

The aim of any TNR programme should be to neuter as many cats as possible early in the effort, to achieve the fastest and most cost-efficient reduction in population numbers. This is when the proportion of unneutered animals is highest. Such programmes are not short-term undertakings and, having attained a decrease or stabilisation in population size, they need to be maintained by continuing to neuter the greatest possible number of cats, for example, every 6 months.3

The most effective method focuses TNR efforts on one geographical location at a time, rather than randomly trapping cats in a large area. Caregivers can act when they notice unneutered cats (no ear-tip) in these locations and can feed the cats with a view to trapping and neutering. It is important to build trust and communicate well with the cat caregivers in the community, so that they can report problems to an organisation or individual who is able to intervene. If the system of prioritising geographical locations causes problems within the community, and there is a risk of losing their engagement, it may be better to focus on ‘hot spots’ of complaints first before progressing to other locations. Modelling of population management protocols suggests it is more effective to target high numbers in smaller geographical areas,15 for example, single streets, if resources are limited, before moving to others.

The overall goal is to:

- Stabilise the population and reduce it in the long term

- Help people and cats to live in harmony

- Improve the general welfare of street cats and other cats in the community

This can only be achieved if TNR is used in conjunction with other strategies, including:

- Community engagement with multiple stakeholders who:

- agree that cats are managed using TNR for street cats, and neutering and homing for any friendly cats and kittens (including those that may be unowned, abandoned or stray pet cats)16

- understand why processes may be in place for pregnant and sick cats, for example, neutering pregnant cats and euthanising sick cats

- Continuing the TNR programme to ensure new cats coming into the area are neutered

- Monitoring of unowned cats by designated feeders/caregivers

- Prevention of abandonment of pet cats

- Neutering of all pet cats

Taking free-roaming kittens from unknown backgrounds with the view to them becoming pet cats requires careful consideration and monitoring of long-term outcomes for the individuals concerned.

Stray, Abandoned and Relinquished Pet Cats Solution: Homing centre or foster care

- Homing centres need to follow Cat Friendly Homing principles (see box), neuter all cats and kittens in their care and actively seek adopters to suit the needs of the individual cat and vice versa

- Homing centres and foster carers should work proactively within their community to assist people who are unable to keep their cats to find them suitable homes, or to help them to overcome problems to enable them to keep their cats

Cat Friendly Homing principles

- Homing centres and foster networks should aim to find cats new homes and should only exist where there is a proven demand for relinquished, abandoned or stray cats

- If possible, only cats that are former pets, or deemed suitable to be pets, should come into homing centres or foster networks. Other cats should be managed through TNR. Some cats may be assessed, after being taken into a homing centre, as not suitable to be pets. These cats will require an ‘alternative lifestyle’, or TNR, and should remain in care for the shortest possible time

- Those caring for the cats should only take in the number of cats they can care for well, in terms of both the cat’s physical health and mental wellbeing

- Good cat husbandry should be in place to ensure that cat stress is minimised and infectious disease outbreaks are reduced/prevented

- Each cat should have individual care and be homed quickly to an environment that suits its needs

- All cats and kittens should be neutered before going to their new homes

- Any kittens born or reared while in care should have positive early exposure to people to ensure they will make good pets and enjoy the experience of being with them

- Length of stay should be kept to a minimum for good welfare and to free up space to increase throughput and help more cats in the long term

Inbetweener cat solution: Alternative lifestyle

Inbetweeners are cats that have previously lived as pets, but unsuccessfully, because they are uncomfortable with the close proximity of people. As a result, they need a lifestyle that includes some support but doesn’t force them to interact with people. This lifestyle may be free-roaming outdoors with food and shelter provided by a person who cares for the cat from a distance. This potentially lends itself to many different environments; for example, hotel grounds, stables, farms and even in large gardens or on private land. They should be neutered and either microchipped or ear-tipped when under general anaesthetic for neutering but become the responsibility of a caregiver who commits to feed and provide shelter and monitor from a distance. These cats should spend the shortest amount of time possible, if any, in confinement.

Other inbetweeners, with specific temperament traits, may need to be near people, even living in homes with free access outside, but will not want the close contact or constant focus that is more typical of a normal owner/cat relationship. A particular type of owner needs to be found for these cats, and given support and guidance to ensure the person understands the commitment required. This owner would need to accept that the conventional bonding associated with a pet is absent and that the individual temperament traits of the cat are permanent.

For more information on inbetweeners see Cat Friendly decision-making: Identifying solutions for inbetweener cats.

Collaborating for cats

Solutions for tackling the number of unneutered cats seen outdoors in the community lie with individuals, charities, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and municipalities/local authorities (depending on the national or local legislation). Budgets are usually small for addressing these issues – there is undoubtedly a need for greater collaboration to achieve successful Cat Friendly Solutions. In addition, proactive measures are needed that address population dynamics before problems occur, to ensure the number of cats can be comfortably sustained by the resources that exist within their environment and that cats don’t cause problems for the human community.

Let’s see what happens when population management solutions are matched to the lifestyles to which cats are adapted, as a ‘bigger picture’. This diagram below shows how the ‘worst-case scenario’, illustrated on page 7, improves considerably if Cat Friendly Solutions are implemented for the long term.

KEY POINTS

Problems arise when unowned cat populations increase and they become a nuisance to the community. When resources cannot sustain the numbers, the cats’ welfare also suffers. Therefore, there is a need for people to take responsibility to control populations of cats and this includes ensuring that all pet cats are neutered. In order to address the problem successfully it is important to understand that the lifestyle of the cat (Felis catus) lies on a spectrum, based on whether the cat wants to live with or avoid people, and whether the cat is adapted to living independently of people outdoors with no restrictions, or is adapted to living in their homes. Hence, different cats need different solutions to meet their needs.

Cats can be described broadly in four ways:

- Feral cat – free-roaming, living away from and avoidant of people, in uninhabited areas at a relatively low population density

- Street cat – free-roaming in inhabited areas at a relatively high population density and reliant on people for food, either provided directly or scavenged from waste bins

- Pet cat – living with people and coping well interacting with them

- Inbetweener cat – a cat that has lived as a pet, but unsuccessfully because it is not comfortable with human interaction

Cats seen outdoors within the community can be a mix of street cats, stray or abandoned pet cats and owned pet cats that have outdoor access. They may be neutered or unneutered.

Cat Friendly Solutions consist of:

- Street cat – Trap, Neuter, Return (TNR), taking them back to their original location after surgery and the removal of the tip of the left ear to aid in identification to prevent the need for further trapping. The TNR process needs to continue to neuter any cats that arrive in the targeted area. A TNR programme should plan to neuter as many cats as possible in the shortest time to be effective in reducing population numbers in the long term

- Friendly free-roaming cats (that may include stray and abandoned pet cats) and relinquished pet cats – Homing centre or foster care, with a view to homing cats as quickly as possible; plus neutering them before they are old enough to reproduce (around 4 months of age)

- Inbetweener cats – Assessment (taking place in a homing centre or foster care) and rapid arrangement of an alternative lifestyle to ensure minimum stay in confinement; plus neutering if not already neutered

- Pet cats – Owners neuter before their cats are able to reproduce (i.e. 4 months of age)

References

| 1. | Driscoll CA, Clutton-Brock J, Kitchener AC, O’Brien SJ. The Taming of the cat. Genetic and archaeological findings hint that wildcats became housecats earlier – and in a different place – than previously thought. Sci Am. 2009 Jun;300(6):68–75. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0609-68 |

| 2. | Humane cat population management guidance from the international companion animal management coalition. https://www.icam-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Humane-cat-population-English.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2023. |

| 3. | Boone JD, Miller PS, Briggs JR, et al. A long-term lens: Cumulative impacts of free-roaming cat management strategy and intensity on preventable cat mortalities. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:238. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00238 |

| 4. | The Cat Group Policy statement: timing of neutering. Accessed August 8, 2023. http://www.thecatgroup.org.uk/policy_statements/neut.html |

| 5. | Cat Population Control Group. Neutering kittens at four months: a summary of the evidence. https://cat-kind.org.uk/media/10659/neu_7999-cpcg-summary-of-evidence_a4_4pp_digital.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2023. |

| 6. | RSPCA Australia research report – Pre-pubertal desexing in cats – June 2021. https://kb.rspca.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2021-06-Pre-Pubertal-Desexing-Report.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2023. |

| 7. | The kitten checklist. https://icatcare.org/advice/the-kitten-checklist/. Accessed August 8, 2023. |

| 8. | Ellis LSH, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15:219–230. doi: 10.1177/1098612X1347753 |

| 9. | Bannasch MJ, Foley JE. Epidemiologic evaluation of multiple respiratoy pathogens in cats in animal shelters. J Fel Med Surg. 2005;7:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2004.07.004 |

| 10. | Tanaka A, Wagner DC, Kass PH, Hurley KF. Associations amon weight loss, stress, and upper respiratory tract infection in shelter cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;240:570–576. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.5.570 |

| 11. | Veir JK, Ruch-Gallie R, Spindel ME, Lappin MR. Prevalence of selected infectious organisms and comparison of two anatomic sampling sites in shelter cats with upper respiratory tract disease. J Fel Med Surg. 2008;10:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.04.002 |

| 12. | Taylor LH, Wallace RM, Balaram D, et al. The role of dog population management in rabies elimination – A review of current approaches and future opportunities. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:109. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2017.00109 |

| 13. | A review of options for cat eradication – Kate F Hurley, UC Davis Koret Shelter Medicine Program. https://icatcare.org/unowned-cats/feral-street-cats/frequently-asked-questions/. |

| 14. | Maggi RG, Halls V, Kramer F, et al. Vector-borne and other pathogens of potential relevance dissemimated by relocated cats. Parasit Vectors. 2022;15:415. doi: 10.1186/s13071-022-05553-8 |

| 15. | From computer models to communities. Strategies to better manage free-roaming cat populations. https://www.acc-d.org/resources/frc-guidance-doc. |

| 16. | Hurley KF, Levy JK. Rethinking the animal shelter’s role in free-roaming cat management. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:847081. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.847081 |