SPECIAL ARTICLE

Cat Friendly Decision-Making

Outcomes for kittens born to free-roaming unowned cats

Vicky Halls, Sarah L.H. Ellis and Claire Bessant

International Cat Care, Place Farm, Tisbury, Wiltshire, United Kingdom

Keywords: Stray kittens, taming feral kittens, feral kittens, pregnant ferals, cat friendly

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2023, 2: 57 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v2.57

Copyright: © 2023 Vicky Halls et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Published: 22 August 2023

Correspondence: Vicky.halls@icatcare.org

This document is intended to provide guidance on appropriate outcomes that meet the individual needs of kittens born to free-roaming unowned cats. This is, by its very nature, a complicated subject, as there are numerous gaps in our understanding regarding the long-term outcomes for these kittens. Therefore, this document adopts the approach that the best outcomes for kittens are ones that are well thought through by those making the decisions, taking into consideration all local and organisational circumstances and the individual kitten’s specific requirements.

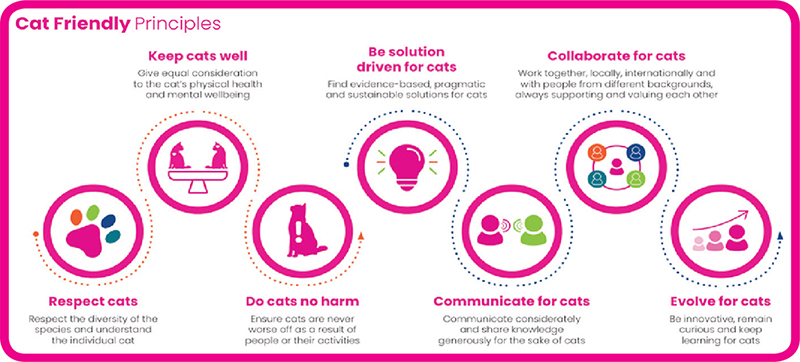

This information would be of interest to anyone in any country working with, or interested in, unowned cats, including cat homing and animal welfare organisations, those undertaking Trap, Neuter, Return (TNR) programmes and veterinarians, veterinary nurses and technicians. In this document, the words ‘cat friendly’ refer to human behaviour that is underpinned by iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles. The word ‘cat’ refers to the domestic cat species Felis catus.

International Cat Care’s (iCatCare’s) series of Cat Friendly decision-making documents are intended to be plain-speaking guides to help those working with cats to navigate complex issues and to aid decision-making where nothing is black and white. They present respectful and carefully reasoned discussions bringing together all aspects of specific topics, including:

- Available science

- Current practice

- Diversity of challenges faced by people working with cats

- Reflection of opinions, beliefs and practices to capture and acknowledge the ‘mood’ to help assess any approach required to improve cat welfare.

They are all underpinned by iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles (see diagram below).

Understanding the topic: outcomes for kittens born to free-roaming unowned cats

In managing cat populations, people in homing organisations or running TNR programmes must find solutions for kittens born to free-roaming unowned cats, which are either picked up as young litters or as part of a TNR programme. There may be conflicting opinions as to what to do for the kittens and inevitably, where young creatures are involved, decisions about their care and outcome stir strong emotions. Many people believe that the best outcome for these kittens is to live as pets. Others may believe that kittens should be returned as part of a TNR programme to their original situation. There are currently no long-term follow-up studies that look at whether outcomes are positive or negative when kittens go into pet homes or how well they survive in the TNR situation. There are anecdotal reports of successful outcomes but equally there are stories of owners being dissatisfied with cats from this background, because they have, for example, remained persistently fearful. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible at the moment, to tease out the exact reasons why some succeed and some fail as pets. At first glance, there are significant pros and cons for each of these two solutions which are dependent on, for example:

- The culture that prevails locally, e.g., tolerance of free-roaming cats

- The availability of pet homes

- The resources available for free-roaming cats, for example, food, shelter and a specific caregiver

- Each individual kitten’s suitability to thrive in the outcome chosen for it

The fundamental question is: what is right for this kitten, given the circumstances, and what information is needed to aid the decision-making process?

What is a kitten?

The kitten lifestage is defined by iCatCare as starting at birth and ending at 6 months of age. This is the most dynamic stage of a cat’s life. Lots of things have to happen quickly during this period to prepare the kitten for independence and survival. This includes a short period during the kitten’s early development when it is much more open to forming relationships, learning what is ‘normal’ in its life and being able to deal with challenges. Experiences at this time can have a profound effect on a kitten’s long-term welfare in terms of the type of lifestyle it is adapted to and comfortable with, and what it considers to be threatening. This includes how cats see people and the human environment. Understanding this can help to make decisions on the outcome for kittens from unowned free-roaming cats.

Where do these kittens come from?

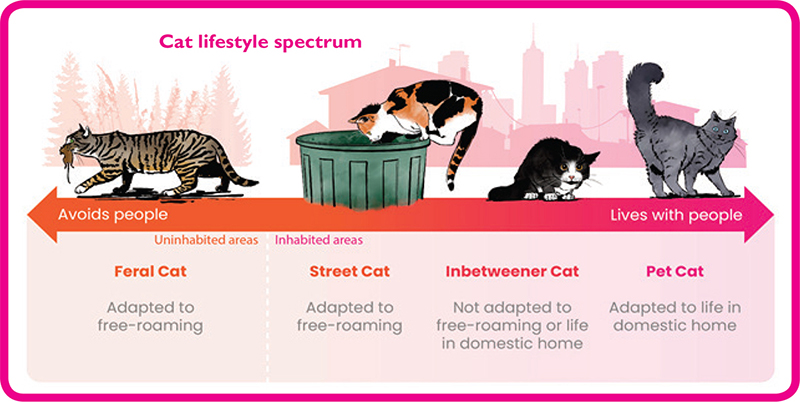

It is important to understand the diversity of the cats which may be the parents of these kittens. This diversity can be illustrated by viewing the potential parents (mother and father) of these kittens on a ‘lifestyle spectrum’, based on two key criteria:

- Whether the cat is capable of living happily with people as a pet or, at the other end of the spectrum, would be distressed living closely with people and would try to avoid them

- Whether the cat is adapted to living independently of people outdoors with no restrictions or, at the other end of the spectrum, is adapted to life in a domestic home (with or without access outside)

Feral cats

These can be described as:

- Born and living outdoors and likely to have come from generations of feral cats

- Living independently of people at a relatively low population density in uninhabited areas

- Likely to be living a solitary lifestyle, mostly hunting for survival

- Kittens of feral cats are not used to people, with no experience of living in a domestic home

Street cats

These can be described as:

- Born and living outdoors

- Free-roaming at a relatively high population density in inhabited areas, e.g., in cities, towns and villages

- Usually gathering with other cats around a plentiful food source (provided by people and/or scavenged from waste bins)

- Showing some tolerance towards familiar people and may even appear friendly

- Not socialised with people as kittens, with no experience of living in a domestic home

- Kittens of street cats may have street or pet cat parents (but are not used to people) and have no experience of living in a domestic home

Pet cats

These can be described as:

- Likely to have come from pet cat parents

- Living with people as companions, either exclusively indoors or with free or limited access outdoors

- Kittens are very likely to have at least one pet cat parent (mother) and to have had early positive experiences with people and the activities within human homes

Inbetweener cats

This is a type of cat, recognised and named by iCatCare as an ‘inbetweener’. The inbetweener is not usually identified until it comes to the attention of a homing centre or foster network. Here the inbetweener is described as:

This feral cat survives in the outback in Queensland, Australia where cat and human density is low

This inbetweener lives in a home but isn’t comfortable being around people and is continuously fearful

This female street cat has recently had kittens, which may be used to seeing people in the town, but have not been handled or had any experience of a human home

This pet cat has been brought up with people and is comfortable living with and being handled by them

- A cat that has previously lived as a pet, but unsuccessfully, because it is uncomfortable with the close proximity of people. This could be because, for example:

- It did not have sufficient or the right quality of interaction with people as a young kitten, so it is distressed in some way around people

- It has a temperament trait that means it can be fearful or anxious of, or frustrated with, people

Kittens may have a mix of parents

Given this diversity and how these types of cats have the potential to interact and breed with each other, it becomes apparent that the cats we see on the streets and their kittens may be a mixture of some of these – those adapted to a free-roaming lifestyle and avoidant of people or pet cats that have strayed or been abandoned. Thus, they potentially have a mix of genetics and no early experience of life as pet cats.

Kitten development in terms of interaction with people

When making any decision about the future of kittens from unowned free-roaming cats, particularly if one of the options is to find them pet homes, it is necessary to understand how kittens develop and what makes them potentially suitable to live alongside people. Cats do not automatically grow up yearning to be part of a human environment which would require them to be comfortable being handled by people and living in their homes. A cat that is able to live with people will potentially benefit from veterinary care and enjoy food, shelter, warmth, and the interactions it has with one or more people. It is understandable that this is the outcome people want for all kittens. However, for some cats, anything involving people can be highly stressful and constitutes a continuing negative experience.

Understanding why these very different scenarios come about enables people to make better decisions about the future for each kitten.

Whether individual cats enjoy living with, or would rather avoid, people is affected by a combination of several things:

- Genes inherited from the parents1,2

- The effect of the environment on the mother when she is pregnant, which is likely to impact on the kittens3–9

Genes inherited from the parents

Research has shown that at least some behavioural tendencies and temperament traits are genetically inherited from parents. For example, if an adult cat frequently displays fearful behaviour towards people, and this has been genetically inherited, then this behaviour has the potential to be passed on to kittens. If a kitten is genetically more likely to be fearful, then getting it used to life as a pet cat and living with people is going to be far more challenging.

Effect of the environment on the mother when she is pregnant, which is likely to impact on the kittens

It has been shown in mammals that stress during pregnancy can lead to what are called ‘epigenetic effects’ in the offspring. This means that stressful environmental conditions may change gene expression in kittens, which may cause them to react more acutely to stress. This can make it difficult for these kittens to become cats which are able to live with people without fear.

Early experiences for the kittens in the first 2 months of life

There is a window of time when a young animal is particularly affected by its surroundings, and when learning and cognitive processing (the way in which animals take in information through the senses and process it) are most efficient. This is called the ‘sensitive period’ and for kittens this occurs in the first 2 months of life when they are most receptive to forming social attachments (bonds with people or other animals) – a process referred to as socialisation. It is a timeframe in an animal’s life when experiences or the lack of them can have a large effect on later life. It is believed that positive experiences with people during this time are vital to developing the brain processes which enable kittens to become cats which enjoy and do not fear human interaction. Relationships that depend on familiarity are formed at this time – so humans and other species, such as dogs, may be incorporated into the cat’s social group and responded to without fear. If the right exposure doesn’t happen, some abilities never, or only partially, develop, resulting in irreversible fear when encountering, for example, people or dogs.

It is also important that kittens get used to sights, sounds, smells, touch sensations and activities that are non-threatening and recognise them as such – this is a process known as ‘habituation’. If this is successful, it enables a kitten to become less reactive to harmless things and to deal with new experiences and events throughout its life. This increases its ability to cope with a changing environment, such as in a domestic home. If kittens are reared in an environment that does not give them the chance to experience, and get used to, things commonly found in a human home (e.g., if they are kept in a bare room or pen where very little happens and they have nothing to explore, or they are born and raised outdoors), the domestic home could be a source of constant stress and fear. They can be at risk of developing ‘problem behaviour’ (such as urine marking) related to anxiety and fear of things which are normally found or occur in a home.

Kittens born and raised in a human home can be given early and positive experiences with people. In this ideal scenario, it is recommended that, between the ages of two and 8 weeks, kittens experience things that socialise them with people and habituate them to life in a domestic home. This includes:

- Being gently touched, lifted and restrained to help to prepare them for the form of handling which is expected by most owners and reduces the potential stress of living with people. It will also prepare kittens for veterinary examinations. This contact should feel positive for the kitten, so all handling should be sensitive, feel secure and occur at a time when the kitten appears receptive

- Meeting a variety of people, to build a tolerance of people generally. Research has shown that kittens that are handled by four or five different people (male, female, adults and children) before they are 7 weeks of age will be more sociable to people as adult cats, and more inclined to initiate social interaction with them. In comparison, cats that are only handled by one individual may be affectionate toward them but view other humans with suspicion and show a tendency to avoid them

- Being handled and spoken to gently for a total of 40–120 min per day, over multiple short sessions, to help them to be more confident to approach people and more inclined to remain in close physical contact. Handling in the presence of a calm mother and littermates will also help this to be a positive experience

- Being exposed gradually and gently to as many sights, sounds, tastes, textures, smells and activities as might be encountered in a normal domestic home lifestyle, eg, vacuum cleaners, washing machines, televisions, different floor coverings and car journeys

Early experiences for the kittens after the first 2 months of life

With the necessary positive early experiences of people and their homes, learning continues beyond the first 2 months of life, as earlier experiences form the positive building blocks for future learning. However, if these experiences have not occurred early enough then, in theory, the ability to socialise a kitten after the age of 8 weeks is greatly compromised. It is interesting to note that many kittens, born to unowned free-roaming cats and without evidence of optimum early socialisation and habituation, appear friendly and many organisations would consider it appropriate to find pet homes for kittens from this background up to 6 months of age. This seems to contradict what would be best practice for preparing a kitten to live as a pet. However, given the diversity of the genetics of free-roaming cats, as described in the previous section, it is entirely possible that kittens from friendly parents may benefit from a socialisation process beyond the accepted window of the sensitive period.

The three factors described above (the kitten’s genetics, the mother’s environment when pregnant and the kitten’s early experiences) do not work in isolation but all contribute to forming the kitten’s temperament that will change very little during its life. The word temperament refers to the way an animal is likely to behave in a range of different circumstances and over time, e.g., a cat with a fearful temperament will appear wary or anxious in lots of different situations, such as the vet clinic or homing centre or with strangers, and will appear so every time, not just on one occasion.

Aging kittens

Images courtesy of Warren Photographic

Being equipped to make decisions about kittens

Decisions regarding outcomes for kittens born to free-roaming unowned cats can be emotional and complex. Understanding what affects how well a kitten can adapt to becoming a pet cat can help homing organisations to ensure that only suitable kittens go through a process aimed at getting them to be able to live comfortably with people. If the decision is made to socialise kittens to enable them to become pets, the aim must be to ensure that the kitten/cat will be comfortable in the home environment, be confident exploring new things and can learn to be relaxed with a number of people. If this is not possible, then other choices have to be made such as returning kittens to TNR sites or finding alternative lifestyles which suit them.

Gathering information and being equipped to think everything through logically and calmly can help – specifically, having an understanding of:

- How kittens develop in terms of their interaction with people. This guides decisions as to whether to try to socialise kittens or not

- How to age kittens (see images on page 5) and how their age may affect success and thus kitten welfare

- The different types of cat and how they sit on the lifestyle spectrum in terms of wanting to avoid people or to be with them (see page 2) and how the temperament and behaviour of the mother may affect the kittens

- The impact of confining a street cat while she is pregnant or has kittens, which can be highly stressful and should therefore be considered in the decision-making

- The demand for kittens locally and the number of adult cats awaiting homes, which may affect what the organisation wishes to prioritise

- The resources available (finances, staff/volunteers, equipment, time, space, knowledge, experience) which may influence choice of approach

- How decisions may affect the kitten, the organisation and staff, the cat population in general, and of course, future owners

- The need for a decision-making process which is clear and gives everyone an opportunity to input, providing a logical and evidence-based approach. This can help to remove some of the purely emotion-based decisions which may be more about human needs than the needs of the cats

- The importance of recording decisions and following up on them, to establish what really happens to kittens in the longer term, allowing for learning and further development of policies

- The implications of hand-rearing, which is time- consuming and must be undertaken in a way which ensures kittens’ physical health as well as getting them prepared for life as pets

- The fact that, most importantly, decision-making is difficult, but not making a decision will not improve the kittens’ situation

Taking on kittens with the aim of finding homes for them as pets

Homing centres may have kittens because the mother has been taken in while pregnant and given birth while confined, they may have litters of young kittens handed in or they may have kittens which have been brought in as a result of a TNR programme where they have been trapped. How to deal with these kittens is a constant source of concern for homing organisations, the majority favouring finding them homes as pets whenever possible. This is achievable in many cases, but still requires a robust system for socialisation and habituation, together with time and knowledge to be successful. However, for some kittens, even the most comprehensive socialisation protocols do not have the desired effect, so what happens if the kittens remain fearful? (See page 7 for signs of positive and negative responses to people.)

What happens if kittens remain fearful?

Problems occur when kittens do not adapt to the socialisation/habituation process and remain fearful. While some will show transient fear, others will remain persistently fearful.

When organisations have kittens which react with fear or behave aggressively towards people there is often a desire to ‘tame’ them, to make them fit for life in a pet home. The use of the word ‘tame’ may well be an indication that they feel that normal socialisation and habituation have not worked and extra methods need to be applied in the process. Methods commonly used to ‘tame’ kittens from free-roaming unowned cats and get them used to people include:

- Touching kittens with padded gloves attached to sticks to get them to accept touch

- Putting them into pouches attached to clothing to experience different sights and sounds

- Placing them in cat carriers or pens in busy rooms in a domestic home so they are forced to experience typical household activities

- Using food rewards to create positive associations

- Rewarding calm behaviour in fearful kittens by leaving the room, apparently to give the kittens a sense of control

All of these methods may not impact negatively on kittens if they are not fearful. However, according to experts in cat behaviour, any of them, when used to ‘tame’ persistently fearful kittens, have a likelihood of causing psychological damage referred to as ‘flooding’12,13. This is because it involves exposing the already fearful kitten to a fear-inducing thing (in this case people) in such a way that the kitten is overwhelmed with fear and it perceives that it cannot escape or hide, so it gives up and ceases to react. The end goal may be perceived as desirable, i.e., the kitten no longer behaves aggressively, or tries to escape, but some kittens may experience prolonged fear which can lead to physical disease in adulthood due to the negative impact that chronic stress has on a cat’s immune system and overall health. Long-term behavioural issues may also occur, such as inability to adapt to new situations and novel objects, or the development of behaviour that the owner finds unacceptable, such as responding aggressively when handled, persistent hiding or house soiling (urinating and defecating in places other than the provided litter trays). Flooding doesn’t require hours of being handled to occur and can quickly become distressing for some kittens. For some, even being in the same room as a person can be a flooding experience. Although there is a body of research on flooding in other species, little is currently known about the longer-term implication of this in the domestic cat. A kitten’s experience of being persistently fearful should not be underestimated or viewed lightly; it is the equivalent to a human experiencing the presence of a threat which that person believes will harm them.

Signs that kittens are responding positively to interaction with people

The kitten is playful with toys

The kitten is interactive and inquisitive about its surroundings with ears facing forward and upright

Signs that kittens are responding negatively to interaction with people (i.e., fearful)

The kitten does not approach but remains still or hidden

The kitten is not interactive or inquisitive about its surroundings.

It has a flattened posture, dilated pupils, flattened ears and a tense body

For those kittens exhibiting mild signs of fear, it may be reasonable to persevere for a week or so and then reassess. For those exhibiting severe signs of fear that do not diminish over several days, this should be a sufficient trigger to discontinue the ‘taming’ process. All physical contact should be stopped and the kitten given somewhere safe where it can hide while awaiting a decision about a different outcome.

What outcomes are then available?

If the kitten is not responding to a socialisation/habituation process or ‘taming’, then, for its welfare, another outcome other than living as a pet is required. A lifestyle may be provided where the kitten (ideally with other similar kittens) can live safely outdoors, for example, in a garden or on a farm with shelter and support from a caregiver from a distance. As young kittens may be in danger from predators, there may be a need to provide a secure and safe environment that is large enough for the kittens to grow and exercise but prevents escape and that also minimises exposure to people. They can then be allowed to roam when they are better able to survive. If kittens were trapped during a TNR programme and are not suitable to be exposed to a socialisation and habituation process (because of age, experience or genetics), it may have been better to have neutered them with their mother and returned them with her, particularly if there is a caregiver to monitor them. This is the expertise the homing or TNR organisation has to develop to make decisions which maximise kitten welfare.

Six steps in decision making

The following describes a challenge a homing centre organisation called Cat Help TNR thought through regarding some kittens in a TNR situation. There are innumerable different situations that provide a chance to explore the options and to try to do the best for the cats and kittens. Here a mother cat has four kittens which have been estimated to be about 8 weeks old. This is a tricky age – it is at the end of the early socialisation period and it is at the beginning of the age when neutering can take place with a competent veterinarian. If the kittens were a few months older they could have been treated like any other unneutered cat in a TNR programme. So what are the possibilities for the future of these kittens? These decisions can be very emotive and having a logical step-by-step process to follow that considers the pros and cons for all of the possibilities can be extremely helpful. This simple six step process involves answering specific questions:

Question 1: What decision needs to be made?

Answer: The mother cat needs to be neutered and returned in the TNR programme, but what do we do with the kittens?

Question 2: Who/what will be affected by the decision?

Answer: All of the following will or could be affected:

- The mother cat

- The kittens

- The cat population in the area

- Cats already waiting with us for homes in the homing centre

- The people in the local community

- Our staff and the organisation itself

Question 3: What are the potential positive or negative impacts of the decision?

Answer: All of the following may be impacted, depending on the decision we make:

- The welfare and quality of life of the mother cat and the kittens

- Use of our resources (finances, time, space)

- Our reputation

- Working relationships with staff, volunteers, veterinary team, future owners, local community, community caregivers of neutered free-roaming cats

- Support from our donors/sponsors/grant makers

Question 4: What can help to inform this decision?

Answer: The following may all be helpful to us:

- The information we hold on space available, demand for space, length of stay of cats, successful outcomes for cats, demand for kittens

- Long-term outcomes for kittens from previous similar decisions we have followed up on

- Our policies or guidelines

- Guidance from iCatCare and other reputable organisations

- Our ability to age kittens accurately

- Our vet clinic’s capacity and capability for early neutering of kittens (around 8 weeks)

- Information from our local community and caregivers

Question 5: What are the options, and pros and cons for each?

Option a: Leave the trapping until we are sure the kittens are over 8 weeks and big enough to be neutered, then TNR the whole family

Pros and cons: The kittens can be neutered as soon as they are caught and there is no risk of them having to be kept in confinement until they are old enough. This allows for them to be returned with the mother, however they may subsequently die or suffer if the environment cannot support them. If we leave the mother any longer, she may become pregnant again. The kittens may be more difficult to trap if left longer and could go on to breed themselves.

Option b: Trap them all now, neuter and return them all to site

Pros and cons: All will be neutered and will not increase the population, but the risk to young kittens is still there. However, we have a dedicated caregiver who has agreed to monitor them and there is plenty of shelter and safe places for kittens to go in that area. If we go for this option, our organisation minimises use of resources. However, if the trappers have overestimated the age of the kittens, they may not be able to be neutered immediately as our veterinarian will only neuter if they are a particular minimum weight and so they may have to be kept until they are old enough, ideally without the mother as confinement for her would be very stressful. Although, younger kittens may have more of a window for socialisation than older kittens so we could start a socialisation programme with them, maybe?

Option c: Trap the mother, neuter her and return her to site, but leave the kittens and plan to trap them when they are older and return to site

Pros and cons: The mother will be neutered and can return immediately to site, we know there is a dedicated caregiver there, so that’s good. However, it may be very difficult to trap the kittens when they are older and they could potentially breed themselves.

Option d: Trap them all, neuter and return the mother and socialise the kittens so they can go to pet homes

Pros and cons: The mother will be neutered and returned to site with the caregiver to look after her. The kittens may be suitable for socialisation and, if the process is done well, they could go successfully to pet homes. This would be the most popular option with the local community, our donors and our staff and volunteers. However, if the kittens are not suitable for socialisation because of their age, experience or genetics, then the socialisation process will be distressing for them and likely to be unsuccessful. A further decision then has to be made about what to do with them, we haven’t had any information from the caregiver to suggest the mother or the kittens are in any way friendly. Anyway, there may not be sufficient people who want kittens and then they may remain in the homing centre or foster home, if we have a suitable one, for an undefined period. Socialising kittens requires more resources from the organisation and the adult cats needing homes we currently have in care may be ignored if kittens are taken instead.

Question 6: Which option is chosen and why?

We have given it a lot of thought and weighed up all the pros and cons for each option and have chosen option

b. We plan to trap all the kittens with the mother as soon as possible, neuter and return them all. Our reasons for choosing this particular option are as follows:

- We have a number of young adult cats in care at the moment, which were trapped and socialised but have not yet been adopted, suggesting the supply of kittens exceeds demand in our area

- We have had experience of unsuccessful socialisation of street kittens where they have remained persistently fearful and the organisation has struggled to find alternative outcomes for them, which is very upsetting for our staff and volunteers

- At the moment our organisation has limited capacity to socialise kittens properly, so feel that we should only undertake this process with kittens we are more confident about being suitable

- The caregiver who feeds the cats in the area has told us that the mother cat is very fearful of people, which might suggest her kittens may not be suitable to become pets

- Our organisation has good experience of aging kittens and estimating their weight from a distance; we feel confident that the kittens are old enough to be neutered and returned with their mother

- Our relationship with our veterinary clinic is good and we have discussed this with them and that these kittens can be safely neutered at this time. We are fortunate to have a veterinarian with the right skills and drugs to neuter young kittens successfully

- The area is not high risk and there is little evidence of high kitten mortality in the free-roaming population here, and we know the local caregiver will take good care of the mother and kittens

We’ve put a plan in place with the caregiver, trappers and veterinary team to trap the mother and kittens. The kittens’ weights will be checked to ensure that neutering can take place, and progress will be monitored by the caregiver when they are returned to the site.

The above is purely an example of one decision in a particular situation under specific circumstances. Every situation is different and the approach and decisions made will vary dependent on many factors. Hard and fast rules may not be beneficial when making this kind of decision, which is why a robust way to view each individual decision can often work better. Following Cat Friendly Principles is all about doing the very best under difficult circumstances. So, if something feels impossible, consider how using the Principles could point to a solution that would have a positive impact. Perfection cannot be achieved as it is not a perfect world. Being pragmatic and satisfied with ‘good enough’ when the ideal seems impossible is a realistic approach.

Testing decision-making

All aspects of work, with and for cats, including attitudes and beliefs, need to be constantly reviewed to ensure that cats are not harmed because of human intervention. As the organisation becomes more experienced and constantly acquires knowledge about the success or otherwise of its work, better decisions can be made. Kittens which are sent to homes should be monitored to ensure they are comfortable in this environment. Likewise, monitoring the future health of kittens returned to their original or other free-roaming location must be undertaken. An open-minded approach to results, and changing approaches if necessary, will help to improve cat welfare. Using a step- by-step tool for decision-making can build expertise and confidence in making these difficult decisions.

KEY POINTS

There are no hard and fast rules when considering outcomes for kittens born to free-roaming cats, as there is huge variation within the species. There are many different factors to consider depending on the location and circumstances and there are gaps in what is known about aspects of the process. With robust and transparent decision-making that takes into account Cat Friendly Principles, it may be possible to work in a variety of different ways and still achieve positive long-term outcomes for the kittens, without compromising their welfare or that of other cats, whether they are returned to a free- roaming outdoor lifestyle or adopted as pets. By considering all the factors, the process of managing these kittens can be potentially more successful in the long-term for the cats and the community within which they live.

- Kittens from unowned cats may have a variety of genetics and early experiences that need to be considered when deciding what is best for their futures

- Kittens are most receptive to forming social bonds (with their own and other species) in the first two months of life

- Kittens that have the potential to become pets, ie, friendly kittens, should be socialised if homes are available

- If the background of the kitten is unknown and a socialisation process is started, it should not be pursued if the kitten is persistently fearful

- If socialisation is not an option, neutering and returning to site for street cats may be indicated (kittens can be neutered from as young as seven to eight weeks of age) as they may be much more comfortable as part of a managed group of street cats

- If the original location is no longer viable, they can be found an alternative lifestyle where they can live safely outdoors with shelter and support from a caregiver who monitors them from afar

- Learning to make decisions and building up expertise by following up on how well kittens are doing in TNR or in homes will help to keep improving activities

References

| 1. | Jensen P. Transgenerational epigenetic effects on animal behaviour. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2013;113(3):447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2013.01.001 |

| 2. | Salonen M, Vapalahti K, Tiira K, et al. Breed differences of heritable behaviour traits in cats. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7949. |

| 3. | Amugongo SK, Hlusko LJ. Impact of maternal prenatal stress on growth of the offspring. Aging Dis. 2014;5(1):1–16. doi: 10.14336/AD.2014.05001 |

| 4. | Braastad BO. Effects of prenatal stress on behaviour of offspring of laboratory and farmed mammals. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;61(2): 159–180. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(98)00188-9 |

| 5. | Coe CL, Lubach GR. Prenatal origins of individual variation in behavior and immunity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29(1):39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.003 |

| 6. | Frye CA, Wawrzycki J. Effect of prenatal stress and gonadal hormone condition on depressive behaviors of female and male rats. Horm Behav. 2003;44(4):319–326. doi: 10.1016/S0018-506X(03)00159-4 |

| 7. | Weinstock M. The long-term behavioural consequences of prenatal stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(6):1073–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.002 |

| 8. | Kay G, Tarcic N, Poltyrev T, Weinstock M. Prenatal stress depresses immune function in rats. Physiol Behav. 1998;63(3):397–402. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(97)00456-3 |

| 9. | Lemaire V, Koehl M, Le Moal M, Abrous DN. Prenatal stress produces learning deficits associated with an inhibition of neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2000;97(20):11032–11037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.11032 |

| 10. | McCune S. The impact of paternity and early socialization on the development of cats behaviour to people and novel objects. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1995; 45: 109–124. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(95)00603-P |

| 11. | Reisner IR, Houpt KA, Hollis NE, Quimby FW. Friendliness to humans and defensive aggression in cats: the influence of handling and paternity. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:1119–1124. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90396-4 |

| 12. | Baum M, Poser EG. Comparison of flooding procedures in animals and man. Behav Res Ther. 1971;9(3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(71)90010-6 |

| 13. | Morganstern KP. Implosive therapy and flooding procedures: a critical review. Psychol Bull. 1973;79(5):318–334. doi: 10.1037/h0034571 |