COMMUNITY CASE STUDY

Playing the Cards You’re Dealt: Implementing Feline Lifesaving Programs and Practices Despite Restrictive Ordinance Provisions

Kailey A. Mauro1 and Peter J. Wolf2*

1Graduate Student (Graduated), Unity Environmental University, New Gloucester, ME, USA; 2Best Friends Animal Society, Kanab, UT, USA

Abstract

Trap-neuter-return (TNR) programs enjoy strong public support in the U.S. These programs have been shown to successfully increase live release rates and decrease euthanasia rates of cats in animal shelters. However, local laws can impede the implementation of TNR programs. In cooperation with St. Tammany Parish Department of Animal Services, this community case study describes the results of various programs and practices implemented to increase feline lifesaving despite restrictive ordinance provisions, as well as those associated with subsequent ordinance revisions. The St. Tammany Parish Department of Animal Services provided detailed data for the period of January 2015 through December 2023 (e.g. intake, live outcomes, and euthanasia) and information regarding various programs and practices related to feline lifesaving. The data was then examined for general trends. In addition, St. Tammany Parish’s Ordinance No. 21-4618, which includes both the original provisions and revised provisions, was examined for those likely to affect the shelter’s feline admissions and outcomes. The data suggests that the programs and practices implemented were associated with considerable increases in live outcomes for cats (from 26.4 to 95.4%) and corresponding reductions in euthanasia rates (from 71.1 to 3.0%). The adoption of revised ordinance provisions to reduce barriers for community cat management was associated with relatively little change; however, these provisions were generally positive in nature, removing an apparent requirement to impound at-large cats and facilitating the operation of a community cat program (CCP). This community case study illustrates the potential for animal shelters to substantially improve feline lifesaving regardless of possible legal impediments.

Keywords: animal shelter; community cats; live-release rate; public policy; trap-neuter-return

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2024, 3: 49 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v3.49

Copyright: © 2024 Kailey A. Mauro and Peter J. Wolf. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 15 March 2023; Revised: 7 August 2024; Accepted: 15 August 2024; Published: 24 September 2024

Competing interests and funding: In recognition of the JSMCAH policy and our ethical obligations as researchers, the authors acknowledge that one of us (P.J.W.) is employed by a national animal welfare organization that promotes TNR and related lifesaving programs. No funding was received in support of this research.

Correspondence: *Peter J. Wolf, 5001 Angel Canyon Road, Kanab, Utah, 84741. Email: peterw@bestfriends.org

Reviewers: Jeanette O’Quin, Benjamin Butina

Supplementary material: Supplementary material for this article can be accessed here.

Heightened ethical considerations for animals have become increasingly apparent over the past few years, with animals seen as having intrinsic value and therefore requiring more humane treatment.1 This shift can be seen in the increasing number of animal shelters that strive for improved lifesaving, as well as in the passing of legislative measures supporting such efforts.2,a,b,c In recent years, U.S. animal shelter data has demonstrated that, generally speaking, live release rates (LRRs) have increased and euthanasia rates have decreased. One study of U.S. shelter data from 2016 to 2020 documented a decrease of 44% in the number of cats and dogs euthanized as share of animals admitted; during this same period, LRRs increased 20% as a share of admissions.3 The desire for increased lifesaving is particularly evident in the evolving management practices for cats. For example, a 2014 survey of U.S. residents revealed that 68% of respondents indicated a preference for trap-neuter-return (TNR) as a management practice, whereas only 24% chose impoundment (‘followed by lethal injection for any cats not adopted’).d Results of a similar survey, conducted 3 years later, showed that 72% of respondents chose TNR while 18% selected impoundment/lethal injection.4

TNR involves the humane trapping of unowned, free-roaming ‘community’ cats, after which they are sterilized and, following recovery, returned to where they were trapped. Many programs also include vaccinations against the rabies virus and other diseases. TNR in the U.S. began largely as a community-based effort.5 However, in recent years, many animal shelters have integrated TNR into their programs, providing live outcomes for many cats who would have been euthanized previously.6–8 These programs, often called return-to-field (RTF) or shelter-neuter-return (SNR), are essentially TNR for cats who are brought to the shelter as strays and meet certain qualifying criteria (e.g. over a certain age limit, no indication of ownership). For the purposes of the present study, we will use the generic term TNR to describe any of these variants.

Implemented with sufficient intensity, targeted TNR has been shown to stabilize and reduce free-roaming cat populations at a local level9–18 as well as reduce the number of cats admitted to, and euthanized at, animal shelters.6–8,19–21 A study of six municipal shelters that integrated community-based and shelter-based TNR programs revealed median declines of 32% in feline intake and 83% in euthanasia over 3 years, accompanied by a median increase of 53% in LRR.6 A more recent study of integrated programs at another municipal shelter revealed a 43% decrease in feline intake and a 94% decrease in euthanasia over 8 years.8 Such results are a key factor in TNR being endorsed by the National Animal Care and Control Association,e and shelter-based TNR now being considered a ‘best practice’ for animal shelters.8

Despite this growing body of research demonstrating the lifesaving benefits of TNR, some communities are faced with legal barriers limiting, or prohibiting altogether, its implementation. Among the most common are provisions of local laws defining ownership of animals, licensing requirements, at-large restrictions, nuisance provisions, and feeding bans.22,f Differing opinions about how to best manage free-roaming cats are reflected in policies created by local and (to a lesser degree) state governments, as well as in public opinion. Some legal objections have focused on potential environmental impacts.g,h Such potential barriers to TNR can obviously have an adverse effect on an animal shelter’s lifesaving efforts.

A 2018 survey of organizations involved with community cats found that less than half of respondents (46.5%) worked under local laws explicitly allowing or endorsing TNR.23 Some national animal welfare organizations recommend that community members, shelters, and municipal leaders carefully examine their local laws in order to determine if certain provisions might impede or even prohibit TNR.i,j Under certain local laws, for example, cats are subject to impoundment due to their stray or at-large status and are kept at the local animal shelter for the required holding period. Doing so puts these cats, as well as other cats in the shelter’s care, at greater risk of euthanasia (e.g. due to disease transmission).24 In addition, cats can, and have been, deemed pests and/or invasive species, providing (in the minds of some) justification for euthanasia.22,k Feeding bans can also be a barrier to TNR, as they impede trapping success9,25 and are likely to disincentivize TNR participation.26,l,m Given the severe consequences that stem from a cat’s legal status, it is important to consider the extent to which ordinance provisions might affect shelter operations and how a shelter might respond to such a situation.

This community case study examines feline lifesaving at the St. Tammany Parish Department of Animal Services (‘St. Tammany’) from January 2015 through December 2023 (hereafter referred to as ‘the study period’). The primary objective of this study was to document the extent to which the shelter programs and practices affected feline lifesaving despite the presence of ordinance provisions limiting positive outcomes for cats.

Background

St. Tammany Parish is located in the state of Louisiana, northeast of New Orleans. Roughly 2,189 km2 in size (not including inland lakes), its population at the time of the 2020 census was 264,570.n The St. Tammany Parish Department of Animal Services is the only municipal animal shelter in the parish, providing sheltering and field services to all residents.

During the study period, St. Tammany experienced years of ordinance provisions limiting positive outcomes for cats. Free-roaming cats would, for example, be considered ‘at large’ and therefore, by definition, a nuisance, thereby increasing the likelihood of impoundment. Following impoundment, the cats would be held for the required holding period of 5 days and made available for adoption. Cats were often euthanized if not adopted, deemed unadoptable upon intake, or if the shelter was lacking space.

Since 2020, prompted largely by public outcry, the shelter has implemented a number of programs and practices aimed at providing more live outcomes for all cats while still complying with the law. These included transfers, Wait ‘til 8, managed intake, volunteer recruitment, field services and the improvement of their TNR program, which was implemented on a small scale the prior year (see Table 1 for details).

In July 2021, the Council of St. Tammany Parish revised several ordinance provisions, with the intent to ‘reduce the population of free-roaming cats, reduce annoyance caused to some people by feral or community cats, [and] positively affect the health and welfare of feral and community cats’ (see Appendix A for additional details). These modifications clarified for St. Tammany the legality of returning cats to their original location after sterilization, vaccination, and ear-tipping. In addition, the new ordinance exempted cats from being impounded for being at large and allowed the shelter to either return a cat or make them available for adoption following the mandatory 5-day holding period.

Methods

Ordinance provisions

Municode Library (library.municode.com), a publicly accessible electronic database, was used to conduct a search of St. Tammany Parish’s Code of Ordinances for both the original provisions (i.e. those in place during most of the study period, dated 2016) and revised provisions, which were adopted on June 3, 2021. A summary of Ordinance No. 21-4618 provisions most relevant to community cat management, which exhibits the TNR-friendly revisions along with the original provisions, is included as Appendix A. For the purposes of the present study, provisions were deemed restrictive if they encouraged or mandated the intake and/or euthanasia of healthy cats. Intake was considered important due to the corresponding possibility and, in many cases, likelihood of cats admitted to the shelter being euthanized.

Data collection

St. Tammany records data as animals enter and leave the shelter using Chameleon (HLP, Inc.), software designed specifically for animal shelters. This data is then typically compiled using Excel (Microsoft Corporation), facilitating its use for internal tracking (e.g. shelter capacity) and reporting to Parish officials. Shelter staff provided intake and outcome data for the period of January 2015 through December 2023. For this study, only data for cats and kittens was considered. Intake sub-categories include owner-surrendered, returns, stray, TNR, and ‘other’ (i.e. cats/kittens confiscated, born at the shelter, or otherwise unaccounted for in intake sub-categories). Outcome sub-categories were divided into live and non-live. Live outcome sub-categories include adoption, return to owner (RTO), transfer out, TNR, and ‘other’ (i.e. cats/kittens listed as missing or relocated). Non-live outcome sub-categories include died in care, euthanasia, and ‘other’ (i.e. deceased cats/kittens brought to the shelter for disposal). In addition, St. Tammany representatives summarized information about the cat-related programs and practices in place during the study period (Table 1).

Data analysis

Data for key intake and outcome sub-categories (e.g. stray intake, adoptions) were compiled for each year of the study period. LRRs were calculated by dividing live outcomes by the number of cats admitted during a particular year.o Euthanasia rates were calculated by dividing euthanasia outcomes by total outcomes. Linear regression was used to evaluate intake categories over time; t-tests were used to compare live and non-live outcomes, LRRs, and euthanasia rates during the years before (2015–2019) and after (2020–2023) the implementation of the lifesaving programs and practices. All statistical analysis was conducted in Excel (Microsoft Corporation, version 16.87).

Over the course of the study period, St. Tammany implemented, with varying intensity, multiple programs aimed specifically at increasing live outcomes for community cats. The available data documented admissions and outcomes at the population level, as is common with shelter records. As a result, specific outcomes could not be traced to specific admissions. It is likely that some cats brought to St. Tammany’s clinic for TNR, for example, were routed to the adoption floor. This was also done with some cats admitted as part of the shelter’s expanded TNR program (Table 1). For this reason, we have combined all TNR-related intake data into one category (i.e. TNR) and all TNR-related outcome data into one category (i.e. TNR). Although doing so sacrifices some granular analysis (e.g. outcomes related to cats brought to the shelter by the public versus those picked up by the shelter’s field services staff), the analysis presented here (i.e. trends in feline admissions and outcomes) is largely unaffected. For example, subtracting all TNR-related admissions from the number of total admissions and total live outcomes—representing the most extreme adjustment possible—decreases the LRR by 1.7–3.9 percentage points for 2021–2023.

Results

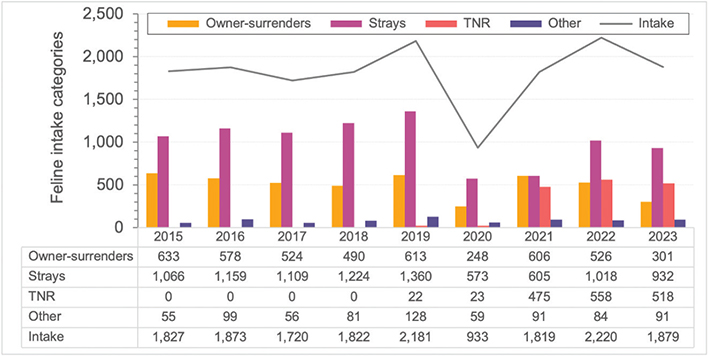

Feline admissions and outcomes

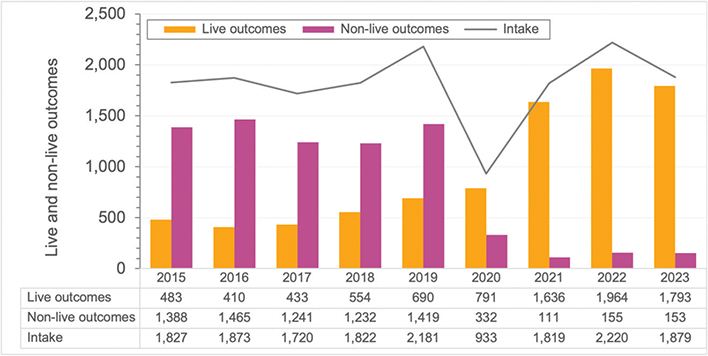

Although the number of cats admitted to the shelter decreased considerably during 2020 and 2021, when pandemic-related restrictions limited shelter admissions (Fig. 1), linear regression analysis revealed no significant difference over the study period (P = 0.86). Live outcomes increased considerably over this period, from 483 in 2015 to 1,793 in 2023, with a particularly substantial increase from 791 in 2020 to 1,636 in 2021. Live outcomes during the years after the implementation of the programs and practices (2020–2023) were significantly greater than those during the period beforehand (2015–2019; t(3) = −3.89, P = 0.03). Meanwhile, non-live outcomes decreased considerably from 1,388 in 2015 to 153 in 2023, with a substantial decrease from 1,419 in 2019 to 332 in 2020. Non-live outcomes during the years after the implementation of the programs and practices (2020–2023) were significantly less than those during the period beforehand (2015–2019; t(7) = 16.81, P < 0.001).

Fig. 1. Annual feline intake, live outcomes, and non-live outcomes from January 2015 through December 2023.

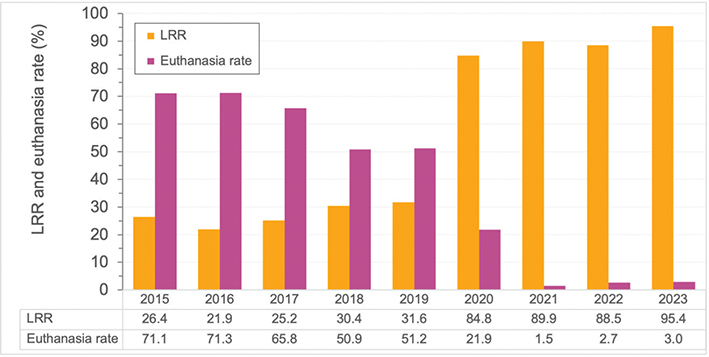

These changes to live and non-live outcomes resulted in corresponding increases in LRR (from 26.4 to 95.4%) and decreases in euthanasia rates (from 71.1 to 3.0%) over the same period (Fig. 2). LRR was significantly higher following the implementation of the programs and practices (t(7) = −22.39, P < 0.001), while the euthanasia rate was significantly lower (t(7) = −8.11, P < 0.001). A detailed summary of annual intakes and outcomes is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Fig. 2. Annual LRRs and euthanasia rates from January 2015 through December 2023.

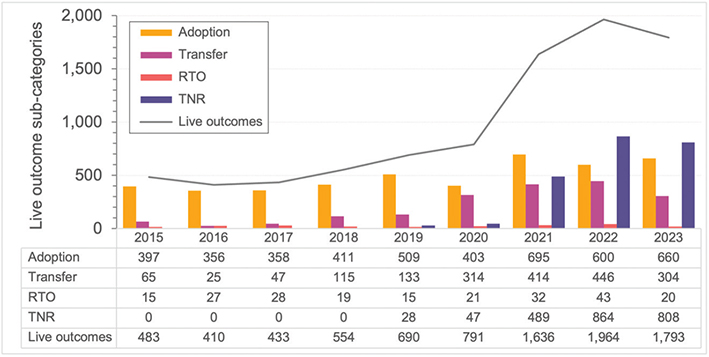

Increases in live outcomes were observed across all sub-categories. Of particular note were live outcomes via transfers (typically to rescue groups), with no more than 65 cats transferred out annually during the first 3 years of the study period, compared to 304–446 during each of the final 4 years. Live outcomes via TNR, which began in 2019 with just 28 cats, exceeded 800 cats in each of the final 2 years of the study period (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Feline live outcomes by sub-category, from January 2015 through December 2023. Note: The sub-category ‘other’ (i.e. cats/kittens listed as missing or relocated), which accounted for no more than 11 cats/kittens in any year, has been omitted to improve clarity.

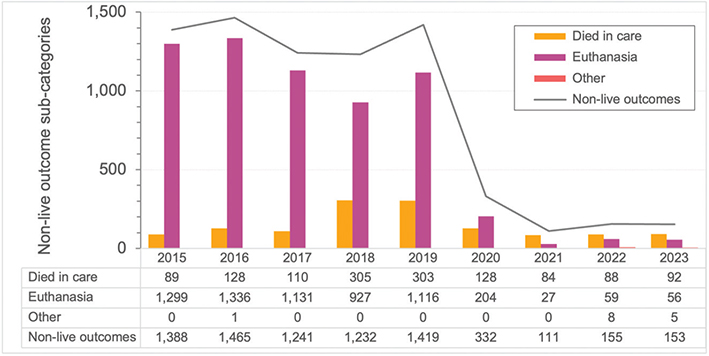

The greatest decrease in non-live outcomes was observed in the number of cats euthanized, from 1,299 in 2015 to 56 in 2023 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Feline non-live outcomes by sub-category, from January 2015 through December 2023. Other non-live outcomes included deceased cats/kittens brought to the shelter for disposal.

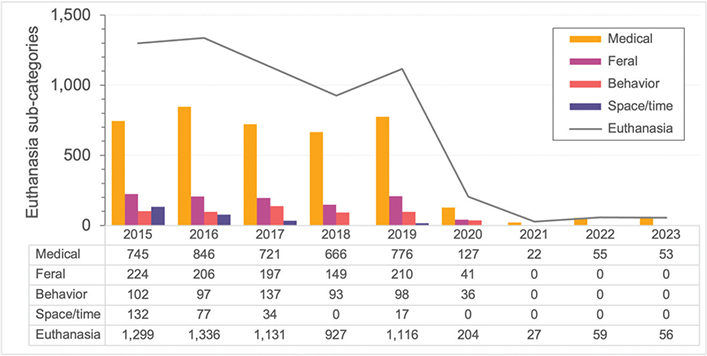

Considerable decreases in the number of cats euthanized annually were observed across all sub-categories. Of particular note was the decrease in cats euthanized for medical reasons, from nearly 750 in 2015 and nearly 850 in 2016, to no more than 55 in each of the final 3 years of the study period (Fig. 5). Upper respiratory infection (URI) made up a considerable share of medical euthanasia, accounting for 333 cats and kittens in 2017, 370 in 2018, and 512 in 2019 (data not shown). By contrast, URI euthanasia accounted for just 14 cats and kittens in 2020. Since then, the number dropped to zero as the shelter fully adopted a process to isolate and treat URI cases.

Fig. 5. Feline euthanasia by sub-category, from January 2015 through December 2023.

Discussion

The primary objective of this retrospective case study was to document the extent to which the programs and practices implemented by St. Tammany affected feline lifesaving despite the presence of ordinance provisions limiting positive outcomes for cats (e.g. an apparent requirement to impound cats found at large). To do so, we examined feline admission and outcome data over 9 years, from January 2015 through December 2023. Live outcomes increased considerably following the shelter’s implementation of several programs and practices aimed at improving feline lifesaving within the constraints of restrictive ordinance provisions (Fig. 1). That same year, a corresponding decrease in non-live outcomes was observed (Fig. 3), and no cats or kittens have been euthanized for space, time (Fig. 5), or age (data not shown) since 2020.

Impact of programs and practices

St. Tammany’s data demonstrated an overall trend of increasing LRR (from 26.4 to 95.4%) and reductions in euthanasia rates (from 71.1 to 3.0%) over the study period. The available data does not allow us to identify specific causal links, in part because of the inherently uneven nature of most program and practice implementation, which typically ramps up relatively slowly and varies in intensity (e.g. depending on season and/or available resources). Launching a Wait ‘til 8 program (Table 1) during the winter months, for example, poses fewer challenges than launching the same program during late spring, well into kitten season.

In addition, it is possible that other factors might help explain these temporal trends in lifesaving. Reducing shelter admissions could, for example, increase LRR without increasing live outcomes. However, except for 2020 (due to pandemic-related restrictions on all shelter admissions), feline intake remained relatively constant over the study period (Fig. 1). Steady feline admission rates suggest that TNR efforts were not targeted geographically and/or undertaken with sufficient intensity27 to produce the reductions in shelter admissions observed elsewhere.6–8,19–21 Rather than reducing overall feline admissions, the programs and practices implemented by St. Tammany seem to have increased the proportion of certain sub-categories while decreasing the proportion of others. For example, the heightened recruitment of volunteers to assist in working with cats with behavioral issues could play a role in reducing the number of cats returned by adopters, whereas their managed intake program likely prevented some owner-relinquished intakes.

The evidence suggests that St. Tammany’s considerable increase in LRRs (Fig. 2) must be attributed to one or more factors other than a reduction in shelter admissions. The shelter’s Wait ‘til 8 program (Table 1) was unlikely to affect admission rates considerably, as it only delays the age of the kittens being admitted into the shelter. However, such programs do provide certain benefits to shelters.p One such benefit is that the neonatal kittens in this program are taken in by a foster family and provided with care and closer monitoring than shelters can typically allocate. This likely contributed to the considerable decrease in non-live outcomes (Fig. 5) and of kittens in particular (Supplementary Table S1). Another contributing factor is St. Tammany’s expanded transfer program. Moving animals out of a receiving shelter that is at (or exceeding) capacity into rescue groups, or other shelters, has been shown to improve live outcomes.2,28,29

Adding to the evidence that the shelter’s programs and practices likely led to improved lifesaving are the mechanisms involved. Transfers out, for example, which increased by an order of magnitude over the study period, are an obvious way to increase LRR while intake remains largely unchanged. Similarly, cats sterilized, vaccinated, and returned as part of a shelter’s TNR program increase LRR, as has been demonstrated in previous studies.6–8,19–21 St. Tammany’s TNR program began very modestly in 2019, with just 22 cats; since 2021, however, TNR admissions account for roughly 500 shelter admissions annually (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Feline admissions by sub-category, from January 2015 through December 2023.

Impact of ordinance changes

It is curious to note that the most dramatic improvements in feline lifesaving occurred prior to the ordinance changes in June 2021. Between 2019 and 2020, St. Tammany’s LRR more than doubled, from 31.6 to 84.8%; between 2020 and 2021, the LRR increased much more gradually, to 89.9%. At first glance, this might suggest that the ordinance changes had little impact on the shelter’s feline lifesaving. Indeed, the greatest gains were achieved with the restrictive provisions still in place, with a LRR of 32% increasing to 85% in just 1 year and a euthanasia rate of 51% decreasing to 2% in 2 years. However, it is likely that the ordinance revision explicitly allowing community cats to be sterilized and returned (Sec. 10-649) was instrumental to increasing live outcomes, as there was no significant change in the number of cats admitted to the shelter as strays over the study period (P = 0.22, Fig. 6). Moreover, these gains were the result of programs and practices implemented at the discretion of shelter leadership; there was no guarantee that the same lifesaving measures would be continued in the future should there be a change in shelter leadership. Research has shown that public administrators ‘who believe that they enjoy higher levels of discretion are more likely to assume the role of steward of public interest’.30 The ordinance revisions are important in that they provide a backstop of sorts, likely preserving some of the gains made prior to their approval should future shelter leaders choose to apply administrative discretion differently.

The ordinance revisions approved by St. Tammany Parish set out not only to reduce the community cat population but to also curb nuisance issues for the community. Along with the infeasibility of eradication and the ineffectiveness of euthanasia as a population management tool,26 such goals have increasingly been the reason behind the implementation of TNR programs.4 These programs have been endorsed by the American Bar Association, which encourages legislative bodies to adopt policies that enable organizations to implement ‘effective, efficient and humane management’ of community cats.q As laws and policies related to community cats are revised, it is also necessary to consider the impacts that irregularities (e.g. leash laws in one community but not in a neighboring community) may have on animal shelter operations, specifically for those shelters that serve multiple jurisdictions, as such irregularities may hinder enforcement of animal welfare and sheltering laws.31

Ordinance provisions vary considerably across municipalities, and many include restrictive provisions similar to those in place in St. Tammany Parish prior to 2021. Data collected over the 9-year study period documented here suggests that considerable improvements in feline lifesaving are possible despite legal impediments.

The benefits of increased bandwidth

In July 2021, St. Tammany Parish’s Code of Ordinances was revised to better manage and provide more live outcomes for community cats. As a result, St. Tammany’s intake of community cats was limited to those for whom they could likely provide live outcomes, as opposed to the communitywide impoundment of cats at large that had been common for years prior. St. Tammany reported that this change, in addition to the programs and practices implemented earlier, allowed for the redistribution of resources to care for animals that may not have received care otherwise. Such a finding has also been observed in other shelters, where resources could be reallocated to animals that may be sick or euthanized under ‘normal’ conditions. Wait ‘til 8 programs, for example, have been shown to reduce kitten euthanasia and may even result in a decrease in shelter admissions.r Indeed, after implementing a Wait ‘til 8 program, St. Tammany’s kitten euthanasia numbers for medical reasons declined consistently (Supplementary Table S1) and euthanasia due to their young age alone ceased (data not shown).

Finally, the programs and practices implemented by St. Tammany required the shelter to engage with the community, often on a personal level, to build trusting relationships. In offering such community- and shelter-based programs to assist with community cats, St. Tammany was able to successfully expand their lifesaving capabilities. These results are comparable to those demonstrated elsewhere,6–8,19–21 suggesting that animal shelters struggling with community cat management consider the implementation of similar programs and practices.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. As noted previously, the available data documented admissions and outcomes at the population level rather than for specific animals (as is common with shelter records). As a result, specific outcomes could not be traced to specific admissions. It is likely that some cats brought to St. Tammany’s clinic for TNR, for example, were routed to the adoption floor. This was also done with some cats admitted as part of the shelter’s expanded TNR program. By combining all TNR-related intake data into one category and all TNR-related outcome data into another category, some level of detail was lost. However, the analysis presented here (i.e. trends in feline admissions and outcomes) was largely unaffected.

Another potential limitation involves the recording and compiling of shelter data, all of which is self-reported and therefore subject to possible errors. Nevertheless, this data is assumed to be as accurate as can be reasonably expected. In addition, the relatively large datasets used for the present analysis offer some ‘protection’ against such errors having a large effect on the results. Unfortunately, the advantages of large datasets do not necessarily apply to summary data tabulated by year; our statistical analyses were hampered by small sample sizes (i.e. just 4 years before and 3 years after implementation of programs and practices).

And finally, it is important to note that, because the data used here reflects programs implemented with different, often uneven levels of intensity, year-to-year comparisons should be interpreted with caution. This is especially true for comparisons to 2020, when pandemic-related restrictions limited shelter admissions.

Conclusion

This community case study set out to determine the extent to which programs and practices affected feline lifesaving despite legal restrictions and, later, in conjunction with revised ordinance provisions. Results revealed that the programs and practices positively influenced St. Tammany’s feline lifesaving. This case study illustrates the potential for animal shelters to substantially improve feline lifesaving regardless of possible legal barriers.

Author credit statement

Kailey A. Mauro: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, visualization.

Peter J. Wolf: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—review & editing, visualization.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation for the staff at St. Tammany Department of Animal Services, who made time in their busy, often chaotic schedules to share detailed data as well as information about their lifesaving programs and practices.

References

| 1. | Wolf PJ, Schaffner JE. The Road to TNR: Examining Trap-Neuter-Return Through the Lens of Our Evolving Ethics. Front Vet Sci. 2019;5:341. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00341 |

| 2. | Hawes S, Ikizler D, Loughney K, Tedeschi P, Morris K. Legislating Components of a Humane City: The Economic Impacts of the Austin, Texas ‘No Kill’ Resolution (City of Austin Resolution 20091105-040). Institute for Human-Animal Connection, Graduate School of Social Work, University of Denver; 2017. |

| 3. | Rodriguez JR, Davis J, Hill S, Wolf PJ, Hawes SM, Morris KN. Trends in Intake and Outcome Data From U.S. Animal Shelters From 2016 to 2020. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:863990. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.863990 |

| 4. | Wolf PJ, Hamilton F. Managing Free-Roaming Cats in U.S. Cities: An Object Lesson in Public Policy and Citizen Action. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2020;44(2):221–242. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2020.1742577 |

| 5. | Berkeley EP. TNR Past Present and Future: A History of the Trap-Neuter-Return Movement. Alley Cat Allies; 2004. |

| 6. | Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. Integrated Return-to-Field and Targeted Trap-Neuter-Vaccinate-Return Programs Result in Reductions of Feline Intake and Euthanasia at Six Municipal Animal Shelters. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6(77). doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00077 |

| 7. | Johnson KL, Cicirelli J. Study of the Effect on Shelter Cat Intakes and Euthanasia from a Shelter Neuter Return Project of 10,080 Cats from March 2010 to June 2014. PeerJ. 2014;2:e646. doi: 10.7717/peerj.646 |

| 8. | Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. The Impact of Return-to-Field and Targeted Trap-Neuter-Return on Feline Intake and Euthanasia at a Municipal Animal Shelter in Jefferson County, Kentucky. Animals. 2020;10(8):1395. doi: 10.3390/ani10081395 |

| 9. | Stoskopf MK, Nutter FB. Analyzing Approaches to Feral Cat Management—One Size Does Not Fit All. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225(9):1361–1364. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.225.1361 |

| 10. | Natoli E, Maragliano L, Cariola G, et al. Management of Feral Domestic Cats in The Urban Environment of Rome (Italy). Prev Vet Med. 2006;77(3–4):180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2006.06.005 |

| 11. | Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. A Case Study in Citizen Science: The Effectiveness of a Trap-Neuter-Return Program in a Chicago Neighborhood. Animals. 2018;7(11). Accessed Feb 14, 2024. http://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/8/1/14 |

| 12. | Levy JK, Gale DW, Gale LA. Evaluation of the Effect of a Long-Term Trap-Neuter-Return and Adoption Program on a Free-Roaming Cat Population. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222(1):42–46. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.222.42 |

| 13. | Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. Back to School: An Updated Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Long-Term Trap-Neuter-Return Program on a University’s Free-Roaming Cat Population. Animals. 2019;9(10):768. doi: 10.3390/ani9100768 |

| 14. | Kreisler RE, Cornell HN, Levy JK. Decrease in Population and Increase in Welfare of Community Cats in a Twenty-Three Year Trap-Neuter-Return Program in Key Largo, FL: The ORCAT Program. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6(7). doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00007 |

| 15. | Tennent J, Downs CT. Abundance and Home Ranges of Feral Cats in an Urban Conservancy Where There Is Supplemental Feeding: A Case Study from South Africa. Afr Zool. 2008;43(2):218–229. doi: 10.3377/1562-7020-43.2.218 |

| 16. | Jones AL, Downs CT. Managing Feral Cats on a University’s Campuses: How Many Are There and Is Sterilization Having an Effect? J Appl Anim Welfare Sci. 2011;14(4):304–320. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2011.600186 |

| 17. | Tan K, Rand J, Morton J. Trap-Neuter-Return Activities in Urban Stray Cat Colonies in Australia. Animals. 2017;7(6):46. doi: 10.3390/ani7060046 |

| 18. | Zaunbrecher KI, Smith RE. Neutering of Feral Cats as An Alternative to Eradication Programs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993;203(3):449–452. doi: 10.2460/javma.1993.203.03.449 |

| 19. | Levy JK, Isaza NM, Scott KC. Effect of High-Impact Targeted Trap-Neuter-Return and Adoption of Community Cats on Cat Intake to a Shelter. Vet J. 2014;201(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.05.001 |

| 20. | Kreisler RE, Pugh AA, Pemberton K, Pizano S. The Impact of Incorporating Multiple Best Practices on Live Outcomes for a Municipal Animal Shelter in Memphis, TN. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9. Accessed Nov 15, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.786866 |

| 21. | Hamilton F. Implementing Nonlethal Solutions for Free-Roaming Cat Management in a County in the Southeastern United States. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:259. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00259 |

| 22. | Schaffner JE. Community Cats: Changing the Legal Paradigm for the Management of So-Called ‘Pests’. Syracuse Law Rev. 2017;67(1):71–113. |

| 23. | Aeluro S, Buchanan JM, Boone JD, Rabinowitz PM. ‘State of the Mewnion’: Practices of Feral Cat Care and Advocacy Organizations in the United States. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8. Accessed Nov 12, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2021.791134 |

| 24. | Karsten CL, Wagner DC, Kass PH, Hurley KF. An Observational Study of the Relationship between Capacity for Care as an Animal Shelter Management Model and Cat Health, Adoption and Death in Three Animal Shelters. Vet J. 2017;227:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.08.003 |

| 25. | Normand CM. Feral Cat Virus Infection Prevalence, Survival, Population Density, and Multi-Scale Habitat Use in an Exurban Landscape. M.S. Arkansas Tech University; 2014. |

| 26. | Wolf PJ, Weedon GR. An Inconvenient Truth: Targeted TNR Enjoys a Track Record Unmatched by Lethal Methods for Managing Free-Roaming Cats. J Shelter Med Community Animal Health. 2023;2(1). doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.68 |

| 27. | Boone JD, Miller PS, Briggs JR, et al. A Long-Term Lens: Cumulative Impacts of Free-Roaming Cat Management Strategy and Intensity on Preventable Cat Mortalities. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6(238). doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00238 |

| 28. | Reese LA. Community Factors and Animal Shelter Outcomes. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci. 2022;27(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2022.2063021 |

| 29. | Morris KN, Gies DL. Trends in Intake and Outcome Data for Animal Shelters in a Large U.S. Metropolitan Area, 1989 to 2010. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2014;17(1):59–72. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2014.856250 |

| 30. | Roman A. The Roles Assumed by Public Administrators: The Link Between Administrative Discretion and Representation. Public Adm Q. 2015;39(4):595–644. doi: 10.1177/073491491503900403 |

| 31. | Morton R, Hebart ML, Ankeny RA, Whittaker AL. Assessing the Uniformity in Australian Animal Protection Law: A Statutory Comparison. Animals. 2020;11(35). doi: 10.3390/ani11010035 |

Statement of ethics

As the review of ordinances and the collection of animal shelter data and information was conducted through a publicly available source and/or obtained from St. Tammany with permission to use such data for research purposes, no human or animal subject protection oversight or ethical approvals were necessary.

Appendix A

| St. Tammany Parish Code of Ordinances (Chapter 10, Article IV Animal Control and Welfare) |

||

| Original ordinance (relevant to the January 2015–May 2021 portion of study period) |

Revised ordinance (relevant to the June 2021–December 2023 portion of study period) |

|

| Sec. 10-642. Definitions | ||

| At Large | An animal shall be deemed to be at large when: (1) The animal is off the premises of its owner or keeper and not under the immediate control of a responsible person; or (2) The animal is left unattended while outdoors and upon unenclosed land. | A cat shall be considered at large if it is not within the confines of its owner’s home, cat yard, primary enclosure, on a leash longer than six (6) feet, or in the owner’s physical possession. |

| Community Cat | N/A | Community cat means [a]ny altered or unaltered cat, having been found to be at large and lacking identifying information for an owner/keeper and may or may not be feral. Community cats shall be distinguished from other cats by being sterilized, vaccinated against rabies, microchipped, and ear tipped. Qualified community cats shall be exempt from licensing, stray and at-large provisions of this title, and may be exempt from other provision of this title as they pertain to owned animals. |

| Sec. 10-646. Public Nuisance | ||

| (3) Animals at Large | No person shall suffer or permit any animal in his possession, or kept by him about his premises, to run loose, free or at-large on any street, sidewalk, alleyway, highway, common or public square, or upon any unenclosed land, or trespass upon any enclosed or unenclosed lands of another. The term ‘running loose, free or at large’ means not under the immediate control of a competent person and restrained by a substantial chain or leash… | No community cat shall be declared a nuisance solely for running at-large. |

| Sec. 10-647. Animals at large; leash law | ||

| (2) Seizure and Impoundment | Any… animal control officer shall seize any animal found to be at large. Any such animal may be turned over to the parish department of animal services. Animals found at large by the department of animal services may be seized and impounded; or as an alternative, the animal may be seized and returned to the owner or keeper… | The provisions of this subsection shall not apply to community cats. |

| Sec. 10-649. Policies and procedures; adoptions; animals in the custody of the department of animal services. | ||

| (b) Animals brought to the department of animal services (DAS). (2) Found at large. | c. If the animal is not claimed… within the applicable time set forth above… the animal will immediately be put up for adoption…. However, if the animal is deemed not to be adoptable, or the animal is terminally ill or severely injured when brought in, the animal may be euthanized. | The stray hold period for cats is three days… At the end of the 3 day stray hold period, a cat can be put up for adoption or treated as a Community Cat. Community cats are not subject to a stray hold and may be sterilized, ear tipped, microchipped, rabies vaccinated and returned to their outdoor home on a time frame acceptable to the department. |

| Sec. 10-669. Community Cat Management. | ||

| N/A | [If certain requirements are met] the community cat is exempted from licensing, stray, at-large, and other provisions of this title that apply to owned animals. In no event shall a community cat be exempted from the nuisance provisions of this chapter. However, a community cat shall not be deemed a nuisance solely for running at large. 2(e) Any person may file a complaint with Animal Services stipulating the specific community cat. 2(f) Nothing in this Article shall prevent Animal Services from picking up, receiving, or impounding. a community cat for necessary medical treatment, and then releasing the cat when deemed medically appropriate by Animal Services or the Animal Services Veterinarian. |

|

Footnotes

a. Byrne J. Chicago Aldermen Call for All Animal Shelters in City to Become No-Kill Facilities. Chicago Tribune. 2016. Accessed Jun 13, 2018. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-no-kill-shelters-order-met-20161117-story.html

b. Floccari J. No-Kill Resolution Passed for DeKalb County Animal Shelters. WXIA-TV. 2017. Accessed Jun 13, 2018. https://www.11alive.com/article/news/local/no-kill-resolution-passed-for-dekalb-county-animal-shelters/85-491802611

c. Landis K. Madison County Voters Might be Asked to Weigh in On No-Kill Policy for Animal Control. Belleville News-Democrat. 2018. Accessed Jun 13, 2018. http://www.bnd.com/news/local/article212374204.html

d. Orzechowski K. New Survey Reveals Widespread Support for Trap-Neuter-Return. Faunalytics; 2015. Accessed Nov 20, 2023. https://faunalytics.org/new-survey-reveals-widespread-support-for-trap-neuter-return/

e. NACA. Animal Control Intake of Free-Roaming Cats. National Animal Care and Control Association; 2021. Accessed Oct 26, 2021. https://www.nacanet.org/animal-control-intake-of-free-roaming-cats/.

f. ABA. American Bar Association Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section Report to the House of Delegates: Resolution 102B. American Bar Association; 2017. Accessed Nov 20, 2022. https://s3fs.bestfriends.org/s3fs-public/102B_ABA_Reso_and_Report.pdf

g. Larkin E. NY Agrees to Remove 23 Feral Cats from Jones Beach. Courthouse News Service. 2018. Accessed Aug 5, 2023. https://www.courthousenews.com/ny-agrees-to-remove-23-feral-cats-from-jones-beach/

h. Yoshino K. A Catfight Over Neutering Program. Los Angeles Times. 2010. Accessed Sep 3, 2023. https://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-feral-cats17-2010jan17-story.html

i. BFAS. Community Cat Programs Handbook. Best Friends Animal Society; 2023. Accessed Dec 27, 2023. https://network.bestfriends.org/education/manuals-handbooks-playbooks/community-cat-programs-handbook

j. HSUS. Managing Community Cats: A Guide for Municipal Leaders. Humane Society of the United States; 2020. Accessed Dec 27, 2023. https://humanepro.org/sites/default/files/documents/CA_Community_Cats_Guide_SinglePgs_LRez.pdf

k. Walsh E. Advocacy Group Sues East Bay Parks Over Feral Cat Abatement Policy. PleasantonWeekly.com. 2021. Accessed Dec 28, 2023. https://www.pleasantonweekly.com/news/2021/07/25/advocacy-group-sues-east-bay-parks-over-feral-cat-abatement-policy

l. Gartrell N. Antioch Feral Cat Feeding Ban Proves Futile. The Mercury News. 2014. Accessed Dec 28, 2023. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/12/24/antioch-feral-cat-feeding-ban-proves-futile/

m. Begnaud D, Czachor EM. Two Alabama Seniors, Convicted after Feeding Stray Cats, File Appeal and Prepare to Sue Their City. CBS News. 2022. Accessed Dec 28, 2023. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/alabama-seniors-beverly-roberts-mary-alston-convicted-feeding-cats-file-appeal-lawsuit/

n. n.a. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana; United States. U.S. Census Bureau; 2021. Accessed Dec 28, 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/sttammanyparishlouisiana,US/LFE046222

o. ASPCA. What is Your Rate? Understanding the Asilomar Live Release Rate, ASPCA Live Release Rate and Save Rate. 2011. Accessed Jan 14, 2018. http://www.aspcapro.org/sites/pro/files/What%20is%20your%20Rate%2010_2013.pdf

p. ACA. Wait Until 8® Protocol and FAQ. Alley Cat Allies. Accessed Dec 28, 2023. https://www.alleycat.org/resources/wait-until-8-protocol-and-faq/

q. ABA. American Bar Association Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section Report to the House of Delegates: Resolution 102B. American Bar Association; 2017. Accessed Nov 20, 2022. https://s3fs.bestfriends.org/s3fs-public/102B_ABA_Reso_and_Report.pdf

r. ACA. Wait Until 8® Protocol and FAQ. Alley Cat Allies. Accessed Dec 28, 2023. https://www.alleycat.org/resources/wait-until-8-protocol-and-faq/