THE ASSOCIATION OF SHELTER VETERINARIANS’ GUIDELINES FOR STANDARDS OF CARE IN ANIMAL SHELTERS: Second Edition - December 2022

Lena DeTar* DVM, MS, DACVPM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, Ithaca, NY

Erin Doyle* DVM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Boston, MA

Jeanette O’Quin* DVM, MPH, DACVPM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Columbus, OH

Chumkee Aziz DVM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) University of California-Davis, Koret Shelter Medicine Program, Houston, TX

Elizabeth Berliner DVM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine; Canine & Feline Practice) American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Ithaca, NY

Nancy Bradley-Siemens DVM, MNM, MS, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) Shelter and Community Medicine, Midwestern University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Glendale, AZ

Philip Bushby DVM, MS, DACVS Shelter Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Starkville, MS

Staci Cannon DVM, MPH, DACVPM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, Athens, GA

Brian DiGangi DVM, MS, DABVP (Canine & Feline Practice; Shelter Medicine Practice) University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine, Gainesville, FL

Uri Donnett DVM, MS, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) Dane County Humane Society, Madison, WI

Elizabeth Fuller DVM Charleston Animal Society, Charleston, SC

Elise Gingrich DVM, MPH, MS, DACVPM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Fort Collins, CO

Brenda Griffin, DVM, MS, DACVIM (SAIM), DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine, Gainesville, FL

Stephanie Janeczko DVM, MS, DABVP (Canine & Feline Practice; Shelter Medicine Practice), CAWA, American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, New York, NY

Cristie Kamiya DVM, MBA, CAWA Humane Society Silicon Valley, Milpitas, CA

Cynthia Karsten DVM, DABVP (Shelter Medicine Practice) University of California-Davis, Koret Shelter Medicine Program, Sacramento, CA

Sheila Segurson, DVM, DACVB Maddie’s Fund, Pleasanton, CA

Martha Smith-Blackmore DVM Forensic Veterinary Investigations, LLC, Boston, MA

Miranda Spindel DVM, MS Shelter Medicine Help, Fort Collins, CO

*Editors

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2022 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/ASVguidelines.2022

Copyright: © 2022. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Published: 23 January 2023

Acknowledgements

The ASV would like to recognize and thank the authors of the first edition of the ASV Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters for their time and dedication to creating and sharing this transformative document: Sandra Newbury, Mary Blinn, Philip Bushby, Cynthia Barker Cox, Julie Dinnage, Brenda Griffin, Kate Hurley, Natalie Isaza, Wes Jones, Lila Miller, Jeanette O’Quin, Gary Patronek, Martha Smith-Blackmore, Miranda Spindel.

We would like to acknowledge the following people for their assistance with the presentation of this document:

- Dr. Denae Wagner for drafting figures of dog and cat primary enclosure set-up

- Katie Mihalenko for graphic design

- Gene Summerlin for legal consultation

- Abigail Appleton, PMP, CAWA, for technical support creating the checklist of key actionable statements

- Open Academia for publishing services

Introduction

Purpose

The Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ (ASV) Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters [‘The Guidelines1’] was originally published in 2010. While animal sheltering has evolved substantially in the last decade, this second edition shares the same fundamental goals. To provide:

- a set of common standards for the care and welfare of companion animals in shelters based on scientific evidence and expert consensus

- guidance that helps animal welfare organizations reduce overcrowding, stress, disease, and improve safety

- a tool for animal welfare organizations and communities to assess and improve their shelters

- references for creating regulations and statutes around sheltering, and benchmarks for organizational change

- guidance for animal housing in existing facilities and priorities for the design of new construction

- a living document that responds to developments in shelter medicine and animal care research and practice

Both documents share the guiding principle that meeting each animal’s physical and emotional needs is the fundamental obligation of a shelter regardless of the mission of the organization or the challenges involved in meeting those needs.

About this document

This second edition keeps the intent and format of the original document, while incorporating important updates based on the growing body of animal sheltering science and recommendations rooted in practical experience. To undertake this revision, the Board of Directors of the ASV formed a task force of 19 shelter veterinarians from a pool of nominees and original authors. Task force members were selected from those active within the ASV community to provide diversity and breadth in their areas of expertise, geographical locations, and current or previous roles in a variety of shelter types. Task force members completed literature reviews and consulted subject matter experts to inform their contributions. Funding to support the research, development, and publication of this document was provided by the ASV. No commercial or industry funding was used.

This consensus document, which represents the collective input and agreement of all task force members, took 3 years to create. This second edition was approved unanimously by the ASV Board of Directors in December 2022.

Audience

The Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters, Second Edition, is written for organizations of any size or type who provide temporary housing for companion animals. The term shelter used here includes foster-based rescues, nonprofit humane societies and SPCAs, municipal animal services facilities, and hybrid organizations. The Guidelines are also applicable to any organization that routinely cares for populations of companion animals, including companion animal sanctuaries, cat cafés, vet clinics, pet stores, dog breeding operations, research facilities (including universities), and service, military, or sporting dog organizations. This document was written for organizations working in every community, including those with significant numbers of homeless pets, those with the capacity to take in animals from other locations, and those whose pet population challenges vary by species, time of year, and other circumstances.

The term personnel is used in this document to include all paid and volunteer team members caring for animals in shelters and foster-based organizations. This document is intended to guide all personnel, including administrative, medical, behavior, and animal care staff; volunteers; foster caregivers; sole operators; and those filling any other role that supports animal well-being.

Scope

Although many practice recommendations and examples are included, these Guidelines are not a detailed manual for shelter operations. As with the previous document, the aim is to provide guiding standards of care to meet animals’ needs, while allowing shelters to determine exactly how those standards are met in their own operating protocols, based on their mission or mandate, resources, challenges, and community needs.

In this document, we have deliberately limited our focus to the care of cats and dogs who make up the majority of animals admitted to shelters in the United States every year. When caring for other species, similar operational principles can be applied to meet the unique needs of those animals.

The ASV recognizes the importance of activities supporting pet retention and access to veterinary care, and that shelters are playing a large role in providing those services.2 Informed community engagement is critical in supporting the health of animals in their communities, with impacts on shelter intake and human health.3 Although these services are addressed where they intersect with shelter admission and outcome policies and decisions, this document does not focus specifically on how shelters support owned animals or community pet welfare.

Format

These Guidelines have been divided into 13 sections; 11 have been updated from the original document and two are new. The document is intended to be read in its entirety because concepts build upon one another. A glossary is included as Appendix A; a checklist of key actionable statements is available on the ASV website. Lists of helpful resources are also included in appendices for ease of access. As an evidence-based document, the many references included direct the reader to the science and research behind specific recommendations.

As with the original document, the key actionable statements use an unacceptable, must, should, or ideal format:

- Unacceptable indicates practices that need to be avoided or prevented without exception

- Must indicates practices for which adherence is necessary to ensure humane care

- Should indicates practices that are strongly recommended, and compliance is expected in most circumstances

- Ideal indicates practices that are implemented when resources allow

The ASV recognizes that each organization is uniquely situated and faces challenges that may impact their ability to implement the practices recommended. The ranked format of statements allows organizations to set priorities for improving their operations and facilities. This is not a legal document; shelters should be aware that state and local laws and regulations may supersede the recommendations made here.

Ethical framework for animal welfare

The ethical principles for animal welfare used in the original Guidelines document were the Five Freedoms: the freedom from hunger and thirst; the freedom from discomfort; the freedom from pain, injury, or disease; the freedom to express normal behavior; and the freedom from fear and distress.1,4

While these principles are valuable for defining essential elements of animal welfare, their focus is on avoiding negative experiences. Positive experiences and welfare are also essential to promote a life worth living.5 For example, shelters do more than ensure animals do not go hungry; they regularly provide species- and life stage-specific food that nourishes, provides interest, and satisfies without overfilling. Food can be even more enriching when provided in a context of social contact and animal training.

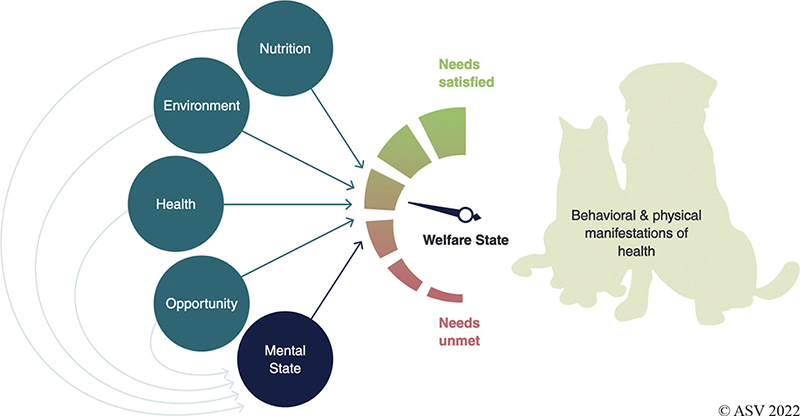

The Five Domains model, derived from the Five Freedoms, illustrates how better or worse nutrition, environment, physical health, and behavioral opportunities combine to inform an animal’s mental state, which, in turn, informs their overall welfare.6 This model does two new things. First, it gives a spectrum for each domain, for example, allowing not just the absence of pain but including the feelings of comfort and fitness (Table 1).

| 1. Nutrition | 2. Environment | 3. Health | 4. Opportunity | 5. Mental state | |

| Positive experiences | Enough food and water Fresh clean water Balanced, variety of food |

Comfortable Temperate Routine Clean Interest/variety |

Physical health Good function Good body condition Restful sleep |

Choice of environment Choice of interaction Behavioral variety (play, hunt, forage, engage, rest) Novelty |

Satisfied Engaged Comfortable Affectionate Playful Confident Calm Encouraged |

| Negative experiences | Restricted water Restricted food Poor quality Monotonous |

Too cold or hot Too dark or bright Too loud or quiet Unpredictable Malodorous Soiled Monotonous Uncomfortable |

Body dysfunction or impairment Disease Pain Poor fitness |

Barren cage Confined space Separation from people or species Restraint Unavoidable sensory inputs |

Fearful or anxious Frustrated Bored, lonely Exhausted Ill, painful Uncomfortable Hungry, thirsty |

| Adapted from Mellor6 | |||||

Second, this model illustrates that positive welfare states can still occur even when one or more important needs are not completely satisfied. For example, a stray cat with a healing pelvic fracture on cage rest (restricted agency, pain) may still have an overall positive welfare state when appropriately treated and housed in an enriched foster home. Negative mental states are also possible even if only one need is unmet. For example, a well-fed and physically healthy dog confined long-term to a kennel (restricted agency) may have profound mental distress and overall negative welfare.

When nutritional, environmental, physical, and emotional needs are increasingly satisfied, animals have increasingly positive mental states and demonstrate this through physical manifestations of good health and behavior (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Five Domains of animal welfare in action

In this document, we set out to help shelters achieve positive welfare in each of these Five Domains within the necessary constraints of animal and human safety and infectious disease control. In addition to following the Guidelines in this document, we hope that shelters will examine existing practices in light of the Five Domains framework and identify new ways to tip the balance toward positive well-being for the animals in their care.

Sheltering today

This document was created during a period of social upheaval, with a global pandemic, climate events, and racial inequity protests impacting communities around the world. Both the COVID-19 pandemic and increasingly frequent damaging weather events have accentuated the critical role that shelters play in keeping animals safe and preserving the human–animal bond. The willingness of communities to help shelters was also highlighted during the pandemic, when entire organizations pivoted to foster care and pursued creative alternatives to intake. Inviting members of the community to be a part of the safety-net has created opportunities for new programs and bigger impacts.

At the same time, the animal welfare industry has been reflecting on how sheltering and animal control practices contribute to systemic inequities in their communities, including the ways that shelters admit, transport, and adopt out animals. This reflection has emphasized the need for accessible, non-punitive services for pet owners in our communities, the benefits of culturally sensitive community engagement, and the need to work toward representing the diversity of our communities in our personnel and profession (ASV’s Commitment to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion).7 Staffing and work environment challenges, during the pandemic and beyond, have reiterated the need for shelters to be healthy, supportive, and inclusive places to work and volunteer (ASV’s Well-being of Shelter Veterinarians and Staff).8

Confronting these challenges together has created a stronger, more interconnected animal welfare community. The ASV offers this document as a tool to help shelters connect to expert guidance and measure themselves against a common standard, to help personnel find compassion satisfaction, to solidify the shelter’s role in supporting their community, and to elevate the welfare of animals in their care.

References

| 1. | Newbury S, Blinn MK, Bushby PA, et al. Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians; 2010:1–67. |

| 2. | Shelter Animals Count. Community Services Data Matrix. 2021:1–10. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://shelteranimalscount-cms-production.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/sac_communityservicesdatamatrix_202101_c1ddc2b4b6.pdf |

| 3. | Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Prinicples of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. Silberberg M, Cook J, Drescher C, McCloskey DJ, Weaver S, Ziegahn L, eds. National Insitutes of Health and Human Services; 2011. |

| 4. | Elischer M. The Five Freedoms: A History Lesson in Animal Care and Welfare. Michigan State University Extension; 2019. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/an_animal_welfare_history_lesson_on_the_five_freedoms |

| 5. | Mellor DJ. Animal emotions, behaviour and the promotion of positive welfare states. N Z Vet J. 2012;60(1):1–8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2011.619047. |

| 6. | Mellor DJ. Updating animalwelfare thinking: moving beyond the “five freedoms” towards “A lifeworth living.” Animals. 2016;6(3):21. doi: 10.3390/ani6030021 |

| 7. | Association of Shelter Veterinarians. ASV’s Commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. 2020. |

| 8. | Association of Shelter Veterinarians. Position Statement: Well-being of Shelter Veterinarians and Staff. 2022. |

1. Management and Record Keeping

1.1 General

A well-run sheltering organization of any size is built on a foundation of planning, training, and oversight. This foundation is an essential part of implementing the guidelines presented in this document. Shelters must have a clearly defined mission or mandate, adequate personnel, up-to-date policies and protocols, a system for training and supervising personnel, and management practices aligned with these guidelines.

The shelter’s mission or mandate should reflect the needs of the community it serves. Tools that aid shelters in defining their purpose include community needs assessments and strategic planning. A community needs assessment reveals what services are already being provided in the community and where needs are unmet. Programs and collaborations have the biggest impact when they reflect principles of community engagement, including respect for each other’s values and cultures.1 The community’s needs should be regularly reviewed, and strategies and goals updated accordingly.

Strategic planning is an organizational process used to define the shelter’s essential programs and goals, and then purposefully allocate resources (e.g. shelter space, personnel, and finances) toward achieving these goals. This planning positively impacts an organization’s ability to achieve its stated objectives.2 Strategic plans are most effective when reviewed regularly, often quarterly, to ensure progress is being made and goals are still relevant.

Animal shelter administration requires the balance of a complex set of considerations, including a focus on collaboration and the establishment of best practices. When developing organizational level policies and protocols, administrators are encouraged to consult industry-specific professional organizations for guidance and to learn from the experience of others in the field.3–5 Because animal health and welfare is woven into every facet of shelter operations, veterinarians should be integrally involved with development and implementation of the shelter’s organizational policies and protocols.

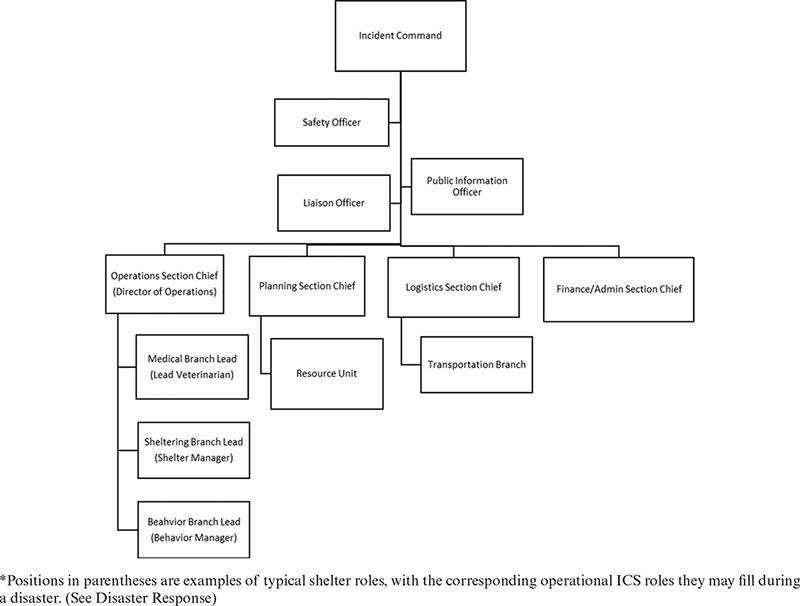

1.2 Management structure

Shelters must have a clearly defined organizational structure that outlines accountability, responsibility, and authority for management decisions. This organizational structure must be communicated to all staff and volunteers. Organizational charts are visual tools that enable all personnel to understand roles and responsibilities, supporting clear communication across departments. This blueprint of the organization can be used by new team members learning about the organization, by those in leadership planning for growth and transition, and by external partners establishing a collaborative relationship with the organization. Lines of authority, responsibility, and supervision should be in writing, reviewed periodically, and updated when roles change.

Decision-making must take into account resource allocation as well as population and individual animal health and welfare. Decisions involving the allocation of resources, whether at the organizational, population, or individual animal level, are best made by personnel aware of organizational priorities and the shelter’s capacity for care.

Authority and responsibility for tasks and decision-making must be given only to those who have the appropriate knowledge, training, and when applicable, credentials. For example, resource-based decisions (e.g. to treat or to euthanize an individual animal) may be made by shelter personnel, but medical treatment decisions (e.g. which drug to treat with) need to involve a veterinarian.

The practice of veterinary medicine and surgery is restricted to those with a valid license. In the United States, veterinary practice is defined by state or territorial practice acts. These acts generally cover the diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions, prescription of pharmaceuticals, surgery, and the tasks that other personnel (e.g. technicians, assistants, veterinary students, and others) may perform under direct or indirect veterinary supervision.6 Several states and the AVMA Model Veterinary Practice Act have sections specific to population medicine and the provision of veterinary oversight through standard written protocols and timely visits to the premises where animals are housed.7,8

Some medical procedures (e.g. microchipping and alternative therapies) may be restricted to veterinarians in some states and not in others.9 Shelters can maximize capacity for medical services by using veterinary technicians and other veterinary professionals to the extent of their capabilities. Providing veterinary care via telemedicine extends veterinary bandwidth and can improve animal welfare.10

A formal relationship with a veterinarian must be in place to ensure oversight of medical and surgical care in the shelter. Many shelters employ one or more veterinarians, others may use local veterinary clinics, and some use paid or unpaid contract veterinarians. A shelter’s veterinarian must have knowledge about their particular population and should have training or experience in shelter medicine. The shelter’s veterinarian should be consulted on all policies and protocols related to the maintenance of medical and behavioral animal health (see Medical Health). Furthermore, veterinarians may be uniquely suited to provide training and continuing education, communicate with external stakeholders, and engage in organizational policy and protocol development in shelters.

1.3 Establishment of policies and protocols

Organizational policies are a framework of high-level decisions that ensure operations remain consistent with the shelter’s mission and priorities. Shelter policies help ensure that animal needs do not overwhelm the resources available to meet those needs, since operating beyond an organization’s capacity for care is unacceptable (see Population Management). Important policies for sheltering organizations include intake, treatable conditions, euthanasia, adoption, transport, and community animal services.

Shelter protocols are critical tools that ensure consistent daily operations in keeping with organizational policies. Protocols must be developed and documented in sufficient detail to achieve and maintain the standards described in this document and should be reviewed and updated regularly. All personnel must have access to up-to-date protocols. How shelters provide this access will vary by organization and may include digital or paper documents. Shelter management must routinely monitor and ensure compliance with protocols. Appendix B provides a comprehensive list of protocols recommended in these Guidelines.

Shelters are obligated to comply with all local, state, and national regulations, which need to be reviewed regularly. In some cases, existing regulations may represent outdated practice or lower standards of care and can restrict or even conflict with current best practices. When implementation of these Guidelines does not align with government regulations or policies, shelters are encouraged to support endeavors for legislative change.

1.4 Training

Effective training of personnel (i.e. paid and unpaid staff and volunteers) is necessary to ensure safe and humane animal care and the safety of people.11 Personnel training should incorporate all relevant aspects of working in the organization. In addition to operating protocols for daily tasks, effective training programs include broader topics that help staff to perform their duties well, such as communication techniques; data management; animal husbandry; staff well-being; and diversity, equity, and inclusion (Appendix B).

Onboarding is an important part of introducing new personnel to any organization. Shelters must provide training for each shelter task, and personnel must demonstrate skills and knowledge before proficiency is assumed. For example, new animal care staff could complete virtual training materials on sanitation and work with a senior staff member prior to being assigned to sanitize enclosures.

Documentation of training should be maintained and reviewed regularly as a part of professional development and performance reviews. Ongoing feedback about performance, both in-the-moment and through formal reviews, is an important element of professional growth for personnel at all levels. When licensing or certification is required to perform specialized duties, as in veterinary care or euthanasia, personnel performing these tasks must be credentialed.12,13 Continuing education must be provided for all personnel in order to improve skills and maintain credentials. Investing in training requires time and resources but is key to program success.

To ensure employee, volunteer, and public safety, shelters must provide all personnel the information and training needed to recognize and protect themselves against common zoonotic conditions (see Public Health). In addition, shelter personnel having any form of contact with animals should have proper training in basic animal handling skills, animal body language, and bite prevention strategies. This training reduces risk for staff and volunteers and provides a more humane experience for animals.

1.5 Record keeping and animal identification

Shelter animal identification and maintenance of animal records are essential for shelter operations. Shelters must adhere to the elements of record-keeping defined within regulatory requirements.

Given the wide availability of technology, digital systems should be used for record keeping, preferably software systems designed for animal shelters. With proper utilization, shelter software or spreadsheet programs allow organizations to better manage resources, schedules, and shelter processes. The software system used by a shelter should be able to generate basic population level reports as well as individual animal records. Population-level data inform management strategies (see Population Management) and allow regular assessment and reporting of organizational goals and activities.14

No matter the system used, each animal must have a unique identifier and individual record. This identifier (e.g. name and number) is established at or prior to admission and ensures consistency and accuracy in care and record keeping for that animal. Shelter software programs typically generate a ‘kennel card’ based on animal information entered into the system, which can be displayed on or near the animal’s primary enclosure for easy reference by personnel and the public.

Because animals may move within and between areas, shelters must have an organized system by which animal identification information can be quickly and easily matched to animals in enclosures and their shelter records. Since identification may be challenging when animals are outside of their enclosures, co-housed with similar animals, or in foster homes, a means of identification should be physically affixed (e.g. collar and tag) or permanently inserted (microchip), when it is safe to do so.

Shelter records should capture all pertinent medical and behavioral information (Table 1.1.) Records must be maintained for animals in foster care and other off-site housing locations just as they are for shelter-housed animals.

References

| 1. | Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Prinicples of Community Engagement. In: Silberberg M, Cook J, Drescher C, McCloskey DJ, Weaver S, Ziegahn L, eds. 2nd ed. National Insitutes of Health and Human Services; 2011, pages 1–188. |

| 2. | George B, Walker RM, Monster J. Does Strategic Planning Improve Organizational Performance? A Meta-Analysis. Public Adm Rev. 2019;79(6):810–819. doi: 10.1111/PUAR.13104 |

| 3. | Association of Animal Welfare Administrators. Resources. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://theaawa.org/page/Resources. |

| 4. | National Animal Care and Control Association. Home: National Animal Care & Control Association. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. www.naca.com |

| 5. | Association of Shelter Veterinarians. Association of Shelter Veterinaians: Home. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. www.sheltervet.org |

| 6. | Association of Shelter Veterinarians. Position Statement: Veterinary Supervision in Animal Shelters. 2021;1. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.sheltervet.org/assets/docs/position-statements/VeterinarySupervision in Animal Shelters PS 2021.pdf. |

| 7. | American Veterinary Medical Association, AVMA. AVMA Policy: Model Veterinary Practice Act. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2021. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/model-veterinary-practice-act.pdf. |

| 8. | American Association of Veterinary State Boards. Veterinary Medicine and Veterinary Technology Practice Act Model (PAM). 2019. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.aavsb.org/board-services/member-board-resources/practice-act-model/. |

| 9. | American Veterinary Medical Association. Policy: Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Veterinary Medicine, Shaumburg IL, 2022. |

| 10. | Association of Shelter Veterinarians. ASV Telemedicine Position Statement. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.sheltervet.org/assets/docs/position-statements/Telemedicine PS 2021.pdf. |

| 11. | National Research Council (U.S.). Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (U.S.). Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press; 2011, Washington DC. |

| 12. | American Association of Veterinary State Boards. Licensing Boards for Veterinary Medicine, Shaumburg IL. |

| 13. | American Veterinary Medical Association. State Laws Governing Euthanasia. 2022. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.avma.org/advocacy/state-and-local-advocacy/state-laws-governing-euthanasia. |

| 14. | Shelter Animals Count. Basic Data Matrix. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.shelteranimalscount.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/BasicDataMatrix_SAC.pdf. |

2. Population Management

2.1 General

Shelters must practice active population management, which is the process of intentionally and efficiently planning services for each animal in the shelter’s care. Individual animals are managed in consideration of the shelter’s ability to care for that animal and their entire population in a manner consistent with the guidelines outlined in this document. Population management includes pre-intake planning, protocols for care and services, ongoing daily evaluation, outcome planning, and response to changing conditions of the shelter and the animal.1

Every organization has limits to its ability to provide care. Limits include financial and physical resources, personnel hours and skills, housing and operations space, and the opportunity for live outcomes. These limitations define the number and type of animals for which an organization can provide humane care, also known as the organization’s capacity for care. The concept of capacity for care is not unique to animal sheltering and is recognized in veterinary hospitals, other animal care fields, human healthcare, hospitality, and other industries.2,3

Operating beyond an organization’s capacity for care is an unacceptable practice. When shelter populations tax the organization’s ability to provide care for their animals, living conditions worsen, and population health and well-being are compromised.4,5 Delays in recognizing problems and providing services negatively impact animal welfare and prolong the length of stay (LOS) for animals in shelters. Alternatively, working to maintain the population within the shelter’s capacity for care has been linked to decreased LOS, decreased disease and euthanasia rates, and increased live outcomes.6,7 Policies and protocols must be in place to ensure an organization operates within its capacity for care.

2.2 Determining capacity for care

The most visible factor in determining the shelter’s capacity for care is housing capacity, or the number of available humane housing units. Housing units include in-shelter enclosures as well as foster homes and off-site housing. Housing capacity calculations must be based on the ability to promote each animal’s positive welfare. Housing units that are too small or otherwise inappropriate cannot be included (see Facilities). The number of humane housing units available may exceed an organization’s capacity for care, since the organization’s capacity is also determined by shelter personnel, resources, and available outcomes.

The time and skills of shelter personnel is another critical component of a shelter’s capacity for care. Trained personnel must be scheduled to meet daily animal care needs and efficiently and effectively accomplish each critical task. A standard estimate such as 15 minutes per animal per day8 may roughly calculate the time needed for cleaning and feeding in some facilities, but it does not account for variations in housing designs and sanitation protocols, the time needed for training personnel, and the provision of enrichment and additional care.9 Personnel time needed for essential care tasks such as sanitation, feeding, and enrichment is best estimated using direct observation to calculate the average time per task. These estimates, when multiplied by the number of animals in care, can guide staffing levels and schedules. Direct observation is also useful for estimating the time needed for personnel to complete other critical tasks, such as intake, rounds, assessments, and outcome processes.

Animals with medical and behavioral challenges may need more care time per day and may also require services from personnel with advanced skills or credentials. When these services are provided by external partners, a shelter’s capacity for care will also be affected by the capacity of these partners. Services such as surgery, veterinary visits, or transport should be scheduled in anticipation of an animal’s eligibility for that service. Proactive scheduling can maximize the use of external partner capacity.

Foster programs must have sufficient personnel to provide support to caregivers and animals. Foster support includes tasks such as maintaining a foster caregiver database, communicating with foster caregivers, scheduling appointments, and facilitating outcomes. Medical, surgical, and behavioral services for foster animals must be provided in a manner that promotes animal welfare and minimizes LOS.

Shelter resources, including finances and material goods, are another critical factor in determining an organization’s capacity for care. If a shelter cannot afford or otherwise procure supplies or necessary services for the animals in their facility, animal welfare will be compromised. There is no standard estimate for calculating cost of care per animal but using historical organizational information and comparing budgets with similar organizations can help shelters manage their available resources.

Shelters should engage with one another to leverage resources and maximize each organization’s strengths. Thoughtful partnerships avoid redundancy and increase the community’s capacity to help animals. For example, a small organization with limited medical resources can partner with a larger organization with a full-service hospital, or a brick-and-mortar organization can partner with a foster-based organization to house animals with kennel-induced stress. In addition to partnering with other animal welfare organizations, collaborating with human service professionals, such as social workers, housing advocates, and home care providers, can support pet retention and prevent relinquishment.

2.3 Operating within capacity for care

Shelters experience a high demand for their services. Working within their capacity for care maximizes each shelter’s impact through thoughtful planning and efficient decision-making. An organization’s policies for admissions and outcomes should be based on their mandate, mission, and the needs of their community. When organizations find that they are frequently near or over their capacity for care, strategic planning can be a valuable process to address how a shelter’s capacity for care and their community’s needs can better align (see Management and Record Keeping).

2.3.1 Admission planning

When appropriate, admission policies should prioritize retention over shelter intake. Helping pets stay with their owner or caregiver preserves the human–animal bond, eliminates the stress of shelter admission, and addresses discriminatory admissions practices.10 Owners may be able to keep their pet if given access to services, supplies, or information.11

Decisions about intake must consider whether admission is the best option for the animal or their situation. Gathering and providing information prior to admission can support intake diversion. For example, finders can be provided information about neonatal kitten care, so that they can rear kittens in their home until they are old enough to be adopted.

Admission must be balanced with the ability to provide appropriate outcomes, minimize LOS, and ensure the shelter remains within its capacity for care. Population management begins prior to admission: an animal must only be admitted if the shelter can provide the care they require. For welfare or safety reasons, some animals may need to be admitted so that euthanasia can be provided.

When admission is deemed the best solution for an animal, situation, and shelter, appropriate intake scheduling ensures that the shelter has the capacity to care for this animal and the animals already in care.12,13 Intake by appointment is recommended even for shelters with high intake demand and open admissions policies and can be used to control the flow of animals into the shelter.11,13,14

Organizations that are impacted by unpredicted intakes (e.g. disasters and large-scale investigations) must have a plan to flex their operations to increase their capacity for care. Compromising the welfare of animals and personnel is not an acceptable strategy for meeting the increased care demands of unpredicted intakes. Increasing a shelter’s capacity requires more than identifying additional humane housing units; all aspects of care need to flex to match, including increased animal care personnel and hours, medical and behavioral care services and providers, resources to supply and fund the response, and a range of available outcomes.15

2.3.2 Outcome planning

Every attempt must be made to locate a lost animal’s owner, including careful screening for identification and microchips, in the field and at the time of intake. Field agents and admissions personnel require ready access to lost pet data and social media in order to cross-check identifying features of animals being picked-up or brought in. Lost pets are usually found close to home and may be returned to their owner without shelter admission.16,17 Reunification of pets can be an opportunity to provide owners with services or information promoting identification (microchipping and ID tags), spay-neuter, training, or fence-building programs. Shelters can also support community members working to reunite animals with their owners directly.

In addition to prioritizing pet retention and reunification, shelters should remove barriers to local outcomes. Removing barriers can include:

- accessible and convenient open hours

- adoption and reclaim services in languages spoken by the community

- affordable adoption and reclaim fees

- adoption and outreach events that reach the entire community

- inclusive adoption policies

Imposing strict policies or requirements on adopters (e.g. employment status, landlord checks, home visits, and veterinary references) is discriminatory, prolongs LOS in the shelter, and prevents future adoptions.18 Strategies that support pet retention, reunification, and local adoption acknowledge the community’s ability and desire to provide care for their pets.

Relocation of animals for adoption can be a valuable strategy for live outcomes while working to address population challenges and remove barriers to local outcomes (see Animal Relocation and Transport). Destination shelters need to critically consider their capacity for care before making the decision to take in transported animals. These programs are not a replacement for partnership building within the local community.

2.3.3 Length of stay

The number of animals a shelter has in its care on any given day is a product of the number of animals it admits and the length of time they stay in the shelter’s care (i.e. LOS).

Average Daily Population = Average Daily Admissions × Average Length of Stay

If two shelters take in the same number of animals each year, the shelter with the shorter average LOS will have fewer animals in care each day (Table 2.1).

Caring for fewer animals at a time allows shelters to provide better welfare and creates the capacity to provide care for animals who require longer stays.1 Or, when it is within the shelter’s capacity and mission to do so, shortening average LOS can allow the shelter to take in more animals or expand other services.

2.3.4 Pathway planning

LOS can be minimized through effective pathway planning. Pathway planning is a proactive process that anticipates the services and care an animal will require to achieve an appropriate outcome.12 A pathway is selected in consideration of available housing, personnel, resources, and the likelihood of achieving the outcome while maintaining good welfare. Planning ahead prevents needless delays that add days to a shelter stay.

Policies that detail which medical and behavioral conditions a shelter can treat help personnel make swift, measured decisions when an animal’s needs may be beyond their ability to provide care. Although legal holding periods and time in medical or foster care may extend the time in care, efficient planning of services can also decrease LOS for these animals.

For shelters with both an on-site and foster population, determining whether to pursue foster placement for an animal is a key part of pathway decision-making. Medical or behavioral care that can reasonably occur outside of the shelter, either in foster care or after adoption, should be identified to minimize time in the shelter environment. Regardless of whether animals are on site or in foster care, decision-making and animal movement must optimize LOS.

2.3.5 Population rounds

To ensure that each animal has a clear plan and that all needs and critical points of service are promptly met, the entire shelter population, including animals housed in foster or off-site, must be regularly assessed by knowledgeable personnel with decision-making ability and authority. The personnel involved in this assessment, often called population or ‘daily’ rounds, will vary based on the shelter population and organizational structure. Population rounds work best when participants include a small group of people who represent relevant departments or teams, including intake, medical, behavior, management, daily care, and outcome personnel (individuals may represent multiple areas). Participants collectively provide and consider all aspects of each animal’s pathway, needs, and next steps.

The population rounds team answers the following for each animal:

- How are you doing?

- What is your pathway?

■ Are there updates or concerns that change this pathway?

- What are your next steps?

The outcome of population rounds is a task list for each participant or team. Any needs identified during population rounds that could compromise welfare or extend the shelter stay must be addressed promptly. Although population rounds are recommended daily for most shelters, it is more important that population rounds occur frequently enough that animal care, including for those in foster, is not delayed.

Additionally, all animals physically in the shelter must be monitored daily to identify housing, care, or service needs. Monitoring these needs helps a shelter determine whether they are within or over their capacity for care. A shelter animal inventory, including all animals in foster care, should be taken and reconciled daily. This ensures that no animals are missing, data collection is accurate, and population levels are within capacity for care. This inventory can be taken during population rounds or daily monitoring.1

2.4 Monitoring population data

Keeping track of shelter metrics and population statistics over time is a key component of successful population management. Population level statistics are available as reports from shelter software programs or can be generated manually using commonly available spreadsheet programs. At a minimum, shelters must track monthly intake and outcome type for each species by age group.19

Data collection should include information about health and behavior status at intake and outcome. Tracking this information allows shelters to understand the effects of shelter care on animal health and well-being. For example, discovering a trend where animals that are healthy at the time of intake subsequently become ill warrants investigation into the shelter’s population management practices.20

LOS data, broken down by age category, species, status, and location, should be regularly analyzed to identify bottlenecks, mismatched resources, and capacity for care concerns.1,9 Population level data should be reviewed and analyzed regularly to ensure that operations align with the organization’s goals, purpose, and policies.9 For example, when an organization’s mandate is to admit stray, injured, or at-risk animals, redirecting healthy community cats to return-to-field services creates capacity to care for the animals that the organization is required to serve.21

Because local capacity to support animal welfare is maximized when organizations collaborate, population level metrics are ideally monitored as a community through transparent sharing of data. Sharing data can help communities strategically leverage resources, increase efficiency, and maximize impact for community animals and people. Organizations can share their data directly or participate in national data sharing databases such as Shelter Animals Count.22 Although useful for tracking shelter goals year over year, outcome-based metrics do not account for quality of life or animals still in the shelter’s care. Live release rates or save rates must be evaluated in the context of animal welfare and cannot be used alone as a measure of success.9 Aversion to euthanasia is not an excuse for crowding and poor welfare.

References

| 1. | Newbury S, Hurley K. Population Management. In: Miller L, Zawistowski S, eds. Shelter Medicine for Veterinarians and Staff. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Wiley Blackwell; 2013:93–113. |

| 2. | Rewa OG, Stelfox HT, Ingolfsson A, et al. Indicators of Intensive Care Unit Capacity Strain: A Systematic Review. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-1975-3 |

| 3. | Alalmai A, Arun A, Alalmai AA, Gunaseelan D. Operational Need and Importance of Capacity Management into Hotel Industry – A Review. Int J Adv Sci Technol. 2020;29(7):122–130. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350616399. |

| 4. | Dybdall K, Strasser R, Katz T, et al. All Together Now: Group Housing for Cats. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2003;11(1):816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.03.001 |

| 5. | Hurley KF, Kraus S, Sykes JE. 17: Prevention and Managment of Infection in Canine Populations. In: Sykes JE, ed. Greene’s Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 5th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022:197–203. |

| 6. | Karsten CL, Wagner DC, Kass PH, Hurley KF. An Observational Study of the Relationship between Capacity for Care as an Animal Shelter Management Model and Cat Health, Adoption and Death in Three Animal Shelters. Vet J. 2017;227:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.08.003 |

| 7. | Janke N, Berke O, Flockhart T, Bateman S, Coe JB. Risk Factors Affecting Length of Stay of Cats in an Animal Shelter : A Case Study at the Guelph Humane Society, 2011–2016. Prev Vet Med. 2017;148(October):44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2017.10.007 |

| 8. | National Animal Care and Control Association. Determining Kennel Staffing Needs. 2020. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.nacanet.org/determining-kennel-staffing-needs. |

| 9. | Scarlett JM, Greenberg MJ, Hoshizaki T. Every Nose Counts: Using Metrics in Animal Shelters. 1st ed. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017. Ithaca NY. |

| 10. | Ly LH, Gordon E, Protopopova A. Inequitable Flow of Animals In and Out of Shelters: Comparison of Community-Level Vulnerability for Owner-Surrendered and Subsequently Adopted Animals. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:784389. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.784389 |

| 11. | Hobson SJ, Bateman S, Coe JB, Oblak M, Veit L. The Impact of Deferred Intake as Part of Capacity for Care (C4C) on Shelter Cat Outcomes. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2021;00(00):1–12. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2021.1894148 |

| 12. | Hurley K, Miller L. In: Miller L, Janeczko S, Hurley K, eds. Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters. 2nd ed. Hoboken, Chapter 1 Introduction to Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters 1–12, NJ: Wiley Blackwell; 2021. |

| 13. | Hurley KF. The Evolving Role of Triage and Appointment-Based Admission to Improve Service, Care and Outcomes in Animal Shelters. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:809340. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.809340 |

| 14. | National Animal Control Association. Guideline on Appointment-Based Pet Intake into Shelters. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.nacanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/NACA-Guideline-on-Appointment-Based-Pet-Intake-into-Shelters.pdf. |

| 15. | Griffin B. Wellness. In: Miller L, Janeczko S, Hurley KF, eds. Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell; 2021:13–45. |

| 16. | Lord LK, Wittum TE, Ferketich AK, Funk JA, Rajala-Schultz PJ. Search and Identification Methods that Owners Use to Find a Lost Dog. JAVMA. 2007;230(2):211–216. |

| 17. | Lord LK, Wittum TE, Ferketich AK, Funk JA, Rajala-Schultz PJ. Search and Identification Methods that Owners Use to Find a Lost Cat. JAVMA. 2007;230(2):217–220. |

| 18. | University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine Shelter Medicine Program. Support for Open Adoptions. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.uwsheltermedicine.com/library/resources/support-for-open-adoptions. |

| 19. | Shelter Animals Count. Basic Data Matrix. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.shelteranimalscount.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/BasicDataMatrix_SAC.pdf. |

| 20. | Scarlett J. Data Surveillance. In: Miller L, Janeczko S, Hurley K, eds. Infectious Disease Management in Animal Shelters. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell; 2021:46–58. |

| 21. | National Animal Care & Control Association. Animal Control Intake of Free-Roaming Cats. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.nacanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Animal-Control-Intake-of-Free-Roaming-Cats.pdf. |

| 22. | Shelter Animals Count. Shelter Animals Count: Home. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://www.shelteranimalscount.org/ |

3. Animal Handling

3.1 General

Safe and humane handling is an essential part of supporting animal well-being. When fear and stress are minimized, animals are calmer and more willing to interact, resulting in safer and more successful interactions. Handling must be humane and appropriate for the individual animal and situation. Humane handling requires

- on-going observation and assessment of behavior with adjustments to the animal’s handling plan as needed

- appropriate choice and management of environment

- sufficient number of trained personnel

- suitable equipment readily available and in good working condition

Considering how animals perceive their environment and making adjustments to minimize potential stressors can reduce or prevent negative emotional responses. These adjustments might include a slow introduction, providing a hiding option during handling (e.g. with a towel), covering a table surface to improve traction, keeping voices low, and the use of gentle but consistent touch to reduce unpredictability.1,2 To create a positive emotional response to human handling, shelter personnel should offer high-value treats or food when handling animals or performing procedures. Treats and toys can engage, distract, and reward animals before, during, and immediately after handling.3,4 When needed, medication should be used to minimize fear, anxiety, and stress and enhance safety during handling5–9 (see Behavior).

3.2 Restraint

Resistance to handling is almost always the result of fear or anxiety. Improper or forceful use of restraint techniques and equipment can escalate a high stress situation, increasing the likelihood of animal or human injury.10 Gentle handling with minimal restraint can improve safety and compliance during care tasks for most animals. The minimal amount of physical restraint needed to accomplish necessary animal care without injury to people or animals must be used.11,12

Forceful restraint methods must not be used, except in extraordinary circumstances. Extraordinary circumstances include situations in which a human or animal is in immediate danger, and other low-stress handling options, sedation, or delays are not possible. Forceful restraint methods include scruffing cats12 or pinning dogs to the ground. For example, a short period of forceful restraint may be required for an animal that needs to be captured and removed from an unsafe environment. Techniques that rely on dominance theory, such as alpha rolls, are inhumane.5,11,13

Alternatives to forceful restraint include distraction with food or toys, positive reinforcement, use of towels, blocking visual stimuli, sedation, and proper use of humane handling equipment (Table 3.1). Selecting a quiet environment, preparing all necessary materials in advance, and involving a person the animal has a bond with can help minimize fear, anxiety, and stress and reduce the restraint required.14,15 If repeated handling is required, training the animal to allow common tasks or to cooperate with handling equipment such as the use of a muzzle is a valuable strategy. Use of sedatives or behavior medications can be the most humane and effective option for frightened, fractious, or feral animals for the delivery of necessary care.1

Handling must minimize the risk of escape. Attention to security of enclosures and carriers, building and vehicle exit points, and minimizing fearful stimuli that trigger flight behavior are important during daily care and when moving animals inside and outside the facility. Being recaptured after escape is profoundly stressful for many animals and creates additional risk of injury to the animal and personnel.4 Delaying handling to allow the animal to calm down can minimize stress and reduce the risk of escape.

3.3 Handling equipment

Using humane handling equipment minimizes animal stress during necessary procedures and daily care, prevents escape, and promotes animal and human safety. For example, rather than carrying a cat in their arms, personnel can transport cats through the shelter in carriers. A variety of humane equipment that facilitates animal handling with minimal or no hands-on contact must be available (Table 3.1). Handling equipment also has the potential to increase fear or injury if used in a forceful manner or not maintained in good working order.

Control poles (i.e. catch poles or rabies poles) are designed to keep a dog’s head at a safe distance from a handler. They are not meant to lift, push, or pull a dog and are not appropriate for routine use. Control poles must only be used when alternatives for handling dogs are insufficient to protect human safety. To prevent the need for daily removal of dogs that are not deemed safe to walk on a leash, double compartment housing is recommended.

Because control poles can cause significant injury and even death, it is unacceptable to use control poles on cats or small dogs. Any restraint method, including control poles, cat tongs, or slip-leads, that causes significant compression of the neck or thorax can cause substantial or life-threatening injury and profound emotional trauma in cats.4,12,16

Animals for whom handling equipment is necessary for long-term safe handling should receive positive reinforcement training to minimize fear, anxiety, and distress during its use.11

Aggressive behavior between dogs can occur unexpectedly for a variety of reasons, and humans can be severely injured when trying to intervene. Animal shelters must have written protocols and readily accessible equipment for breaking up dog fights to prevent human and animal injury. Equipment may include air horns, whistles, citronella spray, blankets, break sticks, panels, and water hoses17,18 (see Behavior).

3.4 Handling feral cats

Specific handling procedures are necessary for feral cats, including the use of live traps, cat dens, squeeze cages, trap dividers, purposely designed cage nets, and multi-compartment enclosures.16,19–21 This equipment permits personnel to safely sedate or anesthetize extremely fearful cats with injectable medication, to provide food and sanitation, to transfer cats from one enclosure to another, and to release outside, all without hands-on handling.

References

| 1. | Moffat K. Addressing Canine and Feline Aggression in the Veterinary Clinic. Vet Clin North Am – Small Anim Pract. 2008;38(5):983–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.04.007 |

| 2. | Griffin B. Fear Free Shelters. 2022. https://fearfreeshelters.com/. |

| 3. | Herron ME, Shreyer T. The Pet-Friendly Veterinary Practice: A Guide for Practitioners. Vet Clin North Am – Small Anim Pract. 2014;44(3):451–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2014.01.010 |

| 4. | Janeczko S. Feline Intake and Assessment. In: Weiss E, Mohan-Gibbons H, Zawistowski S, eds. Animal Behavior for Shelter Veterinarians and Staff. Ames, IA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:191–217. |

| 5. | Hammerle M, Horst C, Levine E, et al. 2015 AAHA Canine and Feline Behavior Management Guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2015;51(4):205–221. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6527 |

| 6. | Stevens BJ, Frantz EM, Orlando JM, et al. Efficacy of a Single Dose of Trazodone Hydrochloride Given to Cats Prior to Veterinary Visits to Reduce Signs of Transport- and Examination-Related Anxiety. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016;249(2):202–207. doi: 10.2460/javma.249.2.202 |

| 7. | van Haaften KA, Eichstadt Forsythe LR, Stelow EA, et al. Effects of a Single Preappointment Dose of Gabapentin on Signs of Stress in Cats during Transportation and Veterinary Examination. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;251(10):1175–1181. doi: 10.2460/javma.251.10.1175 |

| 8. | Pankratz KE, Ferris KK, Griffith EH, Sherman BL. Use of Single-Dose Oral Gabapentin to Attenuate Fear Responses in Cage-Trap Confined Community Cats: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Field Trial. J Feline Med Surg. 2018;20(6):535–543. doi: 10.1177/1098612X17719399 |

| 9. | Erickson A, Harbin K, Macpherson J, Rundle K, Overall KL. A Review of Pre-Appointment Medications to Reduce Fear and Anxiety in Dogs and Cats at Veterinary Visits. Can Vet J. 2021;62(09):952–960. |

| 10. | Herron ME, Shofer FS, Reisner IR. Survey of the Use and Outcome of Confrontational and Non-Confrontational Training Methods in Client-Owned Dogs Showing Undesired Behaviors. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2009;117(1–2):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2008.12.011 |

| 11. | Yin S. Low Stress Handling, Restraint and Behavior Modification of Dogs and Cats. Cattledog Publishing; 2009. Davis CA. |

| 12. | Rodan I, Dowgray N, Carney HC, et al. 2022 AAFP / ISFM Cat Friendly Veterinary Interaction Guidelines: Approach and Handling Techniques. J Feline Med Surg. 2022;24(11):1093–1132. |

| 13. | American Veterinary Society on Animal Behavior. Position Statement on the Use of Dominance Theory. 2008:1–4. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://avsab.ftlbcdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Dominance_Position_Statement-download.pdf. |

| 14. | American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior. Position Statement on Positive Veterinary Care: What Is a Positive Veterinary Experience? 2016. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://avsab.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Positive-Veterinary-Care-Position-Statement-download.pdf. |

| 15. | Taylor S, Denis KS, Collins S, et al. 2022 ISFM/AAFP Cat Friendly Veterinary Environment Guidelines. J Feline Med Surger. 2022;24(11):1133–1163. |

| 16. | Levy JK, Wilford CL. Management of Stray and Feral Community Cats. In: Miller L, Zawistowski SL, eds. Shelter Medicine for Veterinarians and Staff. 2nd ed. Ames, IA; 2013:669–688. |

| 17. | Mullinax L, Sie K, Velez M. Inter-Dog Playgroup Guidelines. Shelter Playgroup Alliance.2019:4–65. |

| 18. | Association of Shelter Veterinarians. Position Statement: Playgroups for Shelter Dogs. 2019. Accessed Dec 13, 2022. https://avsab.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Punishment_Position_Statement-download_-_10-6-. |

| 19. | Slater M. Behavioral ecology of free-roaming/community cats. In: Weiss E, Mohan-Gibbons H, Zawistowski S, eds. Animal Behavior for Shelter Veterinarians and Staff. 1st ed. Ames, IA: Wiley Blacklwell; 2015:102–128. |

| 20. | Griffin B. Care and Control of Community Cats. In: Little S, ed. The Cat: Clinical Medicine and Management. 1st ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:1290–1309. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken NJ. |

| 21. | Griffin B. Care and Control of Community Cats. In: Little S, ed. The Cat. 2011. |

4. Facilities

4.1 General

The facility plays a critical role in the care provided to animals who are admitted into animal shelters. While community-centered sheltering practices and foster programs are reducing the demand for in-shelter care in some areas, providing housing for animals remains an essential part of sheltering operations. Thoughtful planning and use of the shelter building and grounds are important parts of supporting the physical and emotional health of shelter populations while meeting the organization’s mission and goals.1 The shelter facility must include sufficient space to allow for the execution of essential shelter operations and programs as required by mission or mandate.

The quality and set-up of animal housing impacts every aspect of their experience within the facility and plays a pivotal role in managing disease.2 Poor housing is one of the greatest shortcomings observed in shelters and has a substantially negative impact on both health and well-being. Both the quantity and design of housing must be appropriate for the species, the number of animals receiving care, and the expected length of stay. Facility design and use must provide for proper separation of animals by species, predator/prey status, health status, and behavior. Housing in foster care should meet or exceed the guidelines for in-shelter housing.

4.2 Primary enclosures

A primary enclosure is an area of confinement such as a cage, kennel, or housing unit where an animal spends the majority of their time. Shelters must have a variety of housing units available to meet the individual needs of animals, including physical, behavioral, and medical needs. These needs will vary based on species, life stage, individual animal personality, prior socialization, and past experience.1 Appropriate primary enclosures provide complexity and allow choice within the environment to help support positive welfare3 (see Behavior).

The primary enclosure must be structurally sound and maintained in safe, working condition to prevent injury and escape. There can be no sharp edges, gaps, or other defects that could cause injury or trap a limb or other body part. Primary enclosures with wire-mesh bottoms or slatted floors are unacceptable because they can cause pain, discomfort, and injury. Enclosure sides that are entirely wire or chain-link increase the risk of disease transmission, animal stress, and injury. Solid barriers are recommended where animal contact can occur.

The use of cages or crates intended for short-term, temporary confinement or travel is also unacceptable as primary enclosures. These include airline crates, transport carriers, live traps, and wire crates. It is unacceptable to stack or arrange enclosures in a manner that increases animal stress and discomfort, compromises ventilation, or allows for waste material contamination between housing units.

4.2.1 Individual primary enclosure size

Animals must be able to make normal postural adjustments within their primary enclosure, including standing and walking several steps, sitting normally, laying down at full body length, and holding the tail completely erect.1,3–6 Primary enclosure size significantly impacts overall health and well-being. Larger enclosures generally provide animals more choice, permit additional enrichment, and make it possible to safely interact with people and other animals for socialization or cohousing. In cats, sufficiently sized housing reduces stress and respiratory disease incidence.7,8 Individual adult cat housing that is less than 8 ft2 (0.75 m2) of floor space is unacceptable.8 Ideally, individual cat housing provides 11 ft2 (1.0 m2) or more of floor space.7 For dogs, the minimum recommended kennel dimensions differ widely based on body size.9

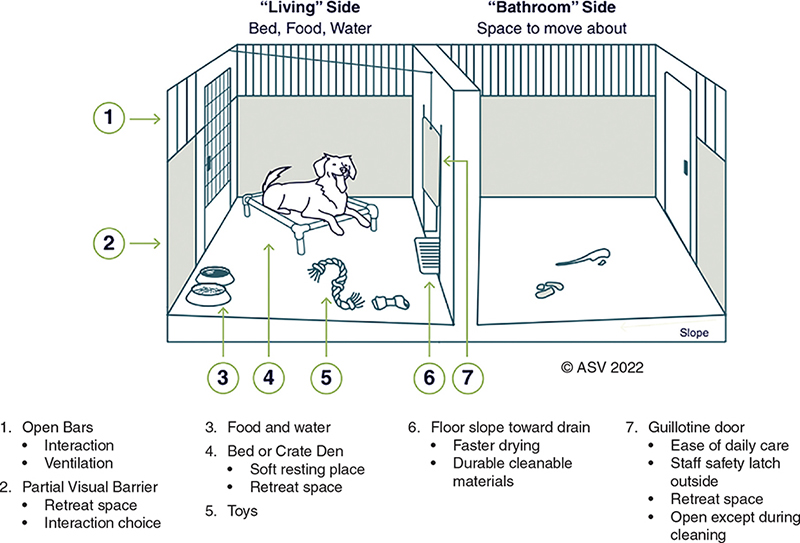

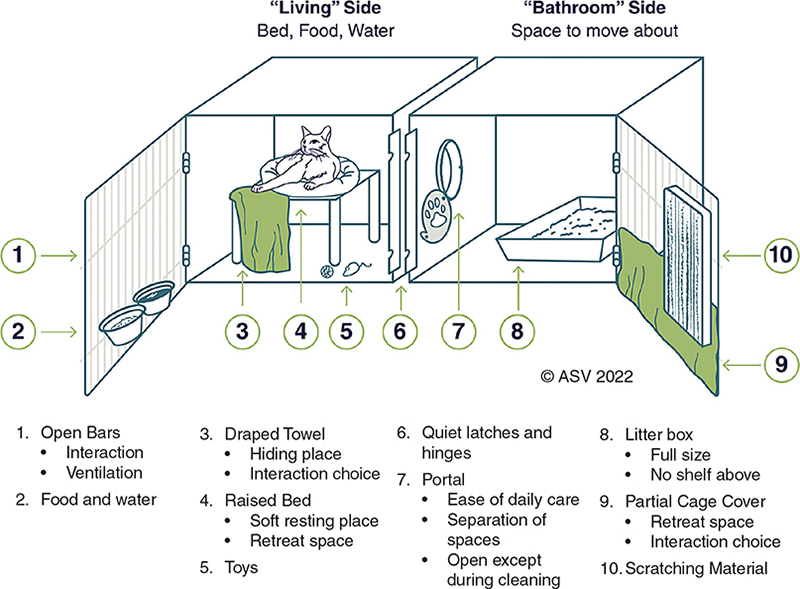

The primary enclosure must allow animals to sit, sleep, and eat away from areas of their enclosures where they defecate and urinate.8 Housing with two or more appropriately sized compartments provides this separation and gives animals more choice and control over their environment and interactions. It also facilitates spot cleaning, reduces fomite transmission, and increases personnel safety3,5 (see Sanitation). Because of all these benefits, multi-compartment enclosures should be provided for the majority of animals housed in the shelter.

Multi-compartment housing is particularly important for newly admitted, fractious, quarantined, sick, and juvenile animals. Enriched room-sized primary enclosures (i.e. real-life rooms) may also benefit from separate elimination areas. Single compartment housing may be necessary for animals with specific medical conditions, which increases the importance of enhanced in-kennel enrichment and supervised out of kennel time (see Behavior).

Cats prefer spending time on raised surfaces and high structures rather than being on the floor.10,11 Cat housing units should be elevated off the floor. Housing cats at human eye level reduces stress, facilitates positive interactions with personnel and visitors, and improves ease of monitoring.5,6,12 Cat cages should face away from each other or be spaced more than 4 ft (1.2 m) apart to prevent droplet transmission of respiratory pathogens while sneezing, coughing, or vocalizing.13–15

Primary enclosures with indoor–outdoor access are ideal for most animals, especially when held long term. Some shelters in temperate climates may have primary enclosures that are fully outdoors. Enclosures that include outdoor space must protect animals from adverse weather; provide choice for thermoregulation; protect from predators; and prevent escape, theft, or harassment. It is recommended that all enclosed outdoor spaces have double-door entry points to keep animals safe and reduce the risk of escape.

4.2.2 Primary enclosure set-up

In addition to the size and structural layout, the set-up of the enclosure and care items provided are important in meeting the welfare needs of shelter animals (Figures 4.1 & 4.2).1 The enclosure needs to be large enough to accommodate the necessary set-up without impeding the animal’s ability to move or stretch.

Figure 4.1. Canine primary enclosure set-up

Figure 4.2. Feline primary enclosure set-up

All dogs should be given the opportunity to hide within their enclosure, especially young, small, fearful, and anxious animals. Options for canine hiding areas include a covered crate within the enclosure or a visual barrier over part of the kennel front.

A soft resting place that elevates animals off of the floor should be made available for all animals to ensure comfort, keep animals dry, and support thermoregulation.

All cats must be given the opportunity to hide within their enclosure. A hiding place provides the choice to be seen or not seen and a place to feel safe and protected.11,16 Options for feline hiding places include feral cat dens, perches covered with towels, cardboard boxes, and partial coverings over enclosure doors. Cats with hiding places spend less time trying to hide and are more likely to approach adopters.17,18

To ensure that cats can display natural behaviors, feline primary enclosures must allow scratching, climbing, and perching. Cats must have a litter box large enough to comfortably accommodate their entire body and allow for proper posturing.19,20 Litter boxes that are too small impact welfare and potentially lead to house soiling behavior.20

4.2.3 Additional considerations

Appropriately sized, enriched primary enclosures are critical for all animals regardless of their length of stay in the shelter. Housing that provides animals with additional space, enrichment, and choice within their enclosure must be provided for animals remaining in the shelter long-term (i.e. more than 2 weeks). Foster care, while beneficial for many animals, can be particularly valuable when animals require a longer length of stay, such as protracted legal holds or long-term medical care.

Animals for whom handling poses an acute welfare or safety risk need to be housed in enclosures that allow humane, touch-free daily care (i.e. multi-compartment). It is unacceptable to house animals in an enclosure that would require the use of forceful animal handling equipment for daily cleaning and care (see Animal Handling).

Except for a brief, emergency situation, it is unacceptable to house animals in facility spaces not intended for animal housing (e.g. bathrooms and hallways). Shelters may have multiuse spaces such as offices set up for animal housing; these planned spaces differ from unplanned practices such as placing temporary kennels in areas unequipped for sanitation or delivery of care.

Tethering is an unacceptable method of confinement for any animal.21 Tethering can cause significant stress and frustration and is best avoided even when used briefly during the cleaning of primary enclosures. Multi-compartment enclosures, thoughtful timing of walks and playgroups, or the use of securely enclosed exercise areas are good alternatives to tethering.

4.3 Cohousing

Cohousing, or keeping more than one animal in an enclosure, can improve animal welfare in some circumstances by facilitating social contact with other animals of the same species.22–29 However, cohousing also known as group housing, is not suitable for every situation. Mental and physical benefits of cohousing need to be carefully weighed against risks to health and safety. If shelters are cohousing animals, they need to prioritize animal well-being and keep population levels within their capacity for care.

4.3.1 Cohousing enclosure set-up

The size and set-up of enclosures used for cohousing require special considerations. The size of a primary enclosure for cohousing must allow each animal to express a variety of normal behaviors and maintain distance from roommates when they choose to do so. Meeting these needs often requires more space per animal than required for individual enclosures, particularly when unfamiliar animals are cohoused. The optimal space requirements for cohousing vary based on species, as well as size, activity level, and behavior.27 A minimum of 18 ft2 (1.7 m2) of floor space per adult cat should be provided for cohousing.4

Quality and complexity of cohousing environments is essential to support the welfare of all animals living in the enclosure.26,30,31 Appropriate resources (e.g. food, water, bedding, litter boxes, and toys) must be provided to minimize competition or resource guarding and ensure access by all cohoused animals. Functional space can be maximized by spacing resources out throughout the enclosure. For cohoused cats, a variety of elevated resting perches and hiding places must be provided to increase complexity and choice within the living space.22,32–36 The ability to choose resting places, social interactions, elimination spaces, and toys contributes to behavioral stability within groups.

Cohousing areas may require enhanced measures to prevent escape. Double door entry at the enclosure’s entrance can provide additional protection when entering or exiting. When housed in a retrofitted area, cats may be able to dislodge ceiling panels or duct covers unless care is taken to secure them.37

4.3.2 Selecting animals for cohousing

Random cohousing of animals in shelters is an unacceptable practice.25 Cohousing requires careful selection of animals by trained personnel to balance the benefits and risks for individual animals and the group. Unrelated or unfamiliar animals must not be cohoused until health and behavior are assessed.27

When cohoused, animals need to be intentionally matched for age, sex, health, and behavioral compatibility. Monitoring after introduction is essential to recognize signs of stress or negative interactions (e.g. guarding food or other resources) that may necessitate separation. Given their increased welfare needs, animals predicted to have longer lengths of stay may benefit most from cohousing, particularly when foster care is not available.

Regardless of the size of the enclosure, no more than six adult cats should be cohoused in a primary enclosure.5 When cohousing is indicated, pairs are preferred for dogs to maximize safety and biosecurity, and no more than two to four adult dogs should be cohoused in a primary enclosure.3 Larger groups of any species are challenging to monitor and increase the risk of conflict and infectious disease transmission. It is preferable to cohouse the minimum number of adult animals together needed to achieve a social benefit.

Housing young puppies and kittens with their mother and littermates is important for physical and emotional development, as well as the establishment of species-specific behaviors. Because of their susceptibility to infectious disease, puppies and kittens under 20 weeks of age must not be cohoused with unfamiliar animals except when the benefits outweigh the risks for all animals involved.38 For example, after a careful medical and behavioral assessment, a single orphaned kitten or puppy may be paired with another orphan or a surrogate mother (see Behavior).

Introducing new animals can result in stress for individuals and the group. Dogs should be introduced outside of their primary enclosures in pairs or groups to determine compatibility prior to cohousing.3,27 In addition, turnover within groups must be minimized to reduce stress and social conflicts as well as the risk of infectious disease exposure and transmission.22,39,40

The use of smaller enclosures with fewer animals, rather than large rooms with large groups of animals, minimizes the need for frequent introductions, group reorganization, and allows for more effective monitoring.41,42 Smaller cohousing spaces facilitate an ‘all-in/all-out’ approach, where all animals leave before more are added. This strategy allows enclosures to be completely sanitized before a new group of animals moves in and eliminates the risks associated with new introductions.

4.3.3 Monitoring cohoused animals

Individual animals and group dynamics must be monitored to recognize signs of stress and social conflicts in cohousing enclosures.24,43 Monitoring, especially after a new animal is introduced into a group and during feeding time, is critical to ensure that all animals are benefitting. In addition to daily monitoring for resource guarding and other signs of social conflict, regular physical examinations including measurement of body weight can ensure that cohoused animals are not suffering due to unrecognized social conflicts.

Not all animals are well suited to cohousing. Individual enriched housing must be provided for animals who are fearful or behave aggressively toward other animals, are stressed by the presence of other animals, require individual monitoring, or are ill and require treatment that cannot be provided in cohousing.22,41 Cohousing animals who fight with one another is unacceptable.

4.4 Isolation housing

Shelters must have a means of isolating infectious animals from the general population to prevent the spread of infectious disease. Isolation housing must meet the medical and behavioral needs of ill animals, including being of sufficient size with appropriate set-up. Different species must not be housed within the same isolation room.1