ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Canine Parvovirus Monoclonal Antibody and Length of Treatment, Cost of Treatment, and Mortality in A Shelter Setting

Stefanie Hornback* and Emmy Ferrell

Oregon Humane Society, Portland, OR, USA

Abstract

Introduction: Canine parvovirus (CPV-2) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in dogs, with often lengthy and expensive treatment that can still end in fatality. In a shelter setting, the length and cost of treatment are important and related factors in being able to provide care for dogs affected with CPV-2. This study examined the addition of canine parvovirus monoclonal antibody (CPMA) to an established treatment program on the length of treatment, cost of treatment, and mortality in a shelter setting.

Methods: This retrospective observational study examined 94 cases of parvovirus diagnosed via IDEXX SNAP testing in a limited admission shelter between the years 2022 and 2024. All cases were treated with the shelter’s standard parvovirus treatment protocol, and 51 of those cases additionally received CPMA. The median length of treatment, average cost of treatment, and mortality rate were compared between those treated with CPMA versus those that were not.

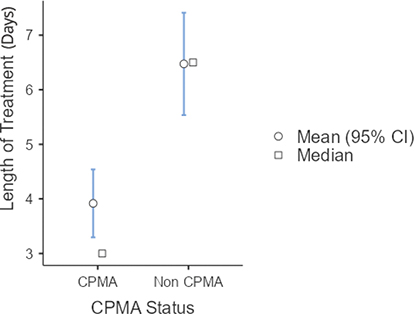

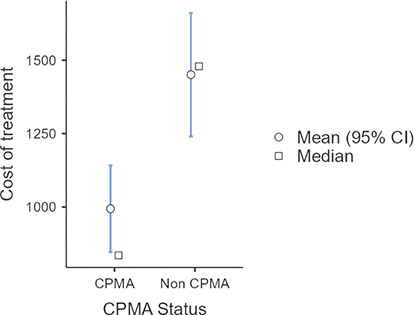

Results: Of the 94 cases examined, 43 were not treated with CPMA and 51 were. The median length of treatment of the CPMA group was 3 days (95% confidence interval, CI [3.3–4.5]) compared to 6.5 days (95% CI [5.5–7.4]) for the control group, a significant decrease for dogs treated with CPMA. The average cost of treatment for the CPMA treated group was $962 (95% CI [$848–$1,140]) compared to $1,447 (95% CI [$1,243–$1,658]) for the control group, also showing a significant decrease. The mortality rate of the CPMA treated group was 6% compared to 12% for the control group; this was lower but ultimately not statistically significant.

Conclusion: The addition of CPMA to established treatment plans for CPV-2 was associated with a significant decrease in the length and cost of treatment, but no significant decrease in the mortality rate.

Keywords: canine; parvovirus; monoclonal; antibody; cost of care; animal shelter

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2025, 4: 159 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v4.159

Copyright: © 2025 Stefanie Hornback and Emily Ferrell. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 22 September 2025, Revised: 28 October 2025, Accepted: 28 October 2025, Published: 8 December 2025

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflict of interest to report. The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Correspondence: *Stefanie Hornback, Oregon Humane Society, 1067 NE Columbia Blvd, Portland, OR 97211, USA. Email: steffie.wagemann@gmail.com

Reviewers: Elizabeth Fuller, Sara White

Since its emergence in 1978, canine parvovirus (CPV-2) has been a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in dogs.1,2 The most susceptible dogs are generally less than 6 months of age, although older dogs are at risk if unvaccinated. After the first few weeks of life, dogs in this age range born to vaccinated mothers have waning maternal antibodies that do not provide full protection but interfere with responses to vaccination.2,3 Puppies born to unvaccinated mothers who are naïve to CPV-2 do not have any antibody protection until vaccination.2,3 Comorbidities such as intestinal parasites and environmental stressors, such as overcrowding, may predispose or exacerbate disease development; thus, animals in a shelter environment may be more susceptible to developing parvoviral enteritis.1,3 Animals may also enter the shelter environment because of CPV-2 diagnosis. Finances are the most commonly reported barrier to veterinary care, so people with economic hardship may feel forced to surrender their dogs to a shelter to provide veterinary care.4

CPV-2 is a highly contagious non-enveloped virus that targets rapidly dividing cells such as the intestinal crypt cells and bone marrow precursor cells.1–3 The virus is shed in the feces and spread mainly through oro-fecal transmission but may also be transmitted through the respiratory tract.1,2,5 Fomites are a significant source of transmission as the virus is stable in the environment, persisting up to 1 year under optimal conditions.1,2 Invasion of the crypt cells leads to the destruction of the mucosal lining of the intestinal tract and malabsorption, as well as bacterial translocation leading to septicemia and endotoxemia. Invasion of the bone marrow precursors leads to a profound leukopenia characterized by a severe neutropenia and lymphopenia, and thus higher susceptibility to septicemia due to immune suppression. Typical clinical signs include vomiting, diarrhea, hematochezia and melena, lethargy, dehydration, and hypovolemic shock.1,2

Treatment for parvovirus has historically consisted of supportive care including fluid therapy, antibiotics, antiemetics, gastroprotectants, and analgesics, with a survival rate ranging from 60 to 90%.1–3 Recently, a canine parvovirus monoclonal antibody (CPMA) that binds to CPV-2 has become available, giving passive immunity and thus acting as a direct treatment for parvovirus infection.5,6 An important part of treatment in a shelter setting also includes isolation from the remaining population. In isolation, people who enter and perform treatments or evaluations on these dogs should wear appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) including foot coverings, water resistant gowns, and gloves. Clinical resolution following treatment is generally based on disappearance of clinical signs as opposed to repeat fecal antigen testing since dogs will continue to shed virus for up to 3–4 weeks after infection.1–3 However, diarrhea may continue to occur despite clinical resolution of other signs due to the destruction of the intestinal villi.

In a shelter setting, as with private owners, finances are a limiting factor in the ability to treat parvovirus.7 Intensive inpatient treatment of parvo may cost $3,000–$5,000 USD with outpatient options still often costing upwards of $1,000.7,8 Length of treatment is a large factor contributing to cost of treatment; thus, a more expensive treatment that decreases length of treatment may actually be more cost-effective. Decreasing length of treatment would also decrease overall shelter length of stay which is important in a shelter setting, as decreasing length of stay has positive impacts on behavior and health.9

The goals of this study were to compare the outcomes of dogs treated with supportive care alone versus supportive care with CPMA to determine if the addition of CPMA was worthwhile in a shelter setting. We hypothesized that the addition of CPMA to established treatment plans would decrease the length of treatment, cost of treatment, and mortality of dogs affected with CPV-2.

Methods and materials

Data was collected from a private limited admissions shelter in the Pacific Northwest with an annual intake of approximately 12,000 animals per year, of which 4,000 are dogs. This shelter routinely treated parvovirus with a standard protocol that included either intensive inpatient treatment with intravenous (IV) fluids, parenteral antibiotics, anti-nausea and anti-emetics, analgesics, and gastroprotectants or outpatient treatment with subcutaneous (SC) fluids, SC antibiotics, and SC anti-emetics. Parvovirus patients were isolated from the general population in a separate area within the shelter. CPMA was available for use at this shelter starting in November 2023.

A total of 94 cases of parvovirus treated in a shelter setting were identified from the shelter’s database (ShelterBuddy) who had complete diagnostic and treatment records. Those included in the study must have been diagnosed with parvovirus and treated in the shelter until an outcome occurred. Diagnosis of parvovirus was based on a positive IDEXX enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) SNAP test elected due to suggestive clinical presentation of the patient. Diagnosis was made either by a community veterinarian prior to transferring the patient to the shelter for care or directly at the shelter. Each animal was given a clinical score ranging from 1 to 5 at time of diagnosis. The clinical score reflected the number of clinical signs present including diarrhea, vomiting, lethargy, anorexia, and fever based on a rectal temperature of 103 degrees Fahrenheit or greater.

Data retrieval began in November 2024 for both groups. Data for dogs treated with CPMA was collected consecutively starting from November 2023 when this shelter began using CPMA until December 2024 when data collection ended. Data for dogs not treated with CMPA, or the control group, was collected consecutively between March 2022 and July 2023 when the shelter was not using CPMA. All CPMA treated dogs received 0.2 mL/kg IV of CPMA within 48 hours of diagnosis. All dogs in both groups were treated with crystalloid fluid therapy (either subcutaneous or IV), at least one antibiotic, and at least one antiemetic. In 35% of the control dogs, and 45% of the CPMA dogs, at least one of the ancillary treatments was added to the treatment plan: analgesics, a second antibiotic, a second antiemetic, gastrointestinal protectants, gastrointestinal prokinetics, or additional fluid therapy. All cases were maintained in an isolation ward dedicated to canine parvovirus cases for the duration of their treatment, and treated by staff wearing disposable PPE. Euthanasia decisions were left up to individual veterinarian discretion, but included lack of response to treatment and clinical decline with intensive inpatient treatment.

A date of clinical resolution was recorded for each case, determined as the day the dog achieved normal appetite, normal mentation and attitude, normal hydration, normal internal body temperature, and no vomiting or nausea. Clinical resolution was determined by clinical signs as opposed to repeat fecal antigen testing because dogs may continue to shed virus for several weeks but not require further treatment. Clinical score was not used as a means of determining clinical resolution because ongoing diarrhea was not included as a criterion. This was chosen because post CPV-2 dogs may have residual diarrhea due to destruction of intestinal villi but no longer be clinical for disease state. Eliminating diarrhea as a criterion may shorten time to clinical resolution, but each group was evaluated in the same manner thus not affecting group comparison. The length of treatment was determined by the number of days from date of diagnosis to date of clinical resolution. The median length of treatment was determined within each of the two groups. Median was used over mean due to data failing normalcy. A log-rank regression analysis was performed to determine the likelihood of survival between the two groups. This also the time to recovery to see if it correlated with the median length of treatment. Time to recovery indicates the probability of survival over defined time frames. The mortality rate between the two groups was determined. Cost of treatment based on length of hospital stay and medications administered was calculated individually using the median weight of all 94 dogs instead of individual weights in order to remove weight discrepancy as a variable. Cost of treatment included a set daily fee for hospitalization based on receiving IV or SC fluids and individual calculation of the cost of each medication administered per day. Once individual cost of treatment was found, the average cost of treatment for each group was determined. A Mann–Whitney U test was used to evaluate length of treatment and cost of treatment, and a Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze mortality. Significance was set to p < 0.05. All data analyses were performed using Jamovi software (version 2.6; The Jamovi project).

Results

A total of 94 cases were reviewed. Out of these, 43 cases (45%) were not treated with CPMA (control group) and 51 cases (55%) were treated with CPMA. The majority of dogs in both the control and CPMA treated groups were less than 5 months of age, had a clinical score of 3, were transferred in from a different shelter, and were either unvaccinated or had an unknown vaccine history (Table 1). Although the majority of dogs in the CPMA treated group were less than 5 months old, the average age was pulled higher by a group of older infected dogs surrendered to the shelter from one source.

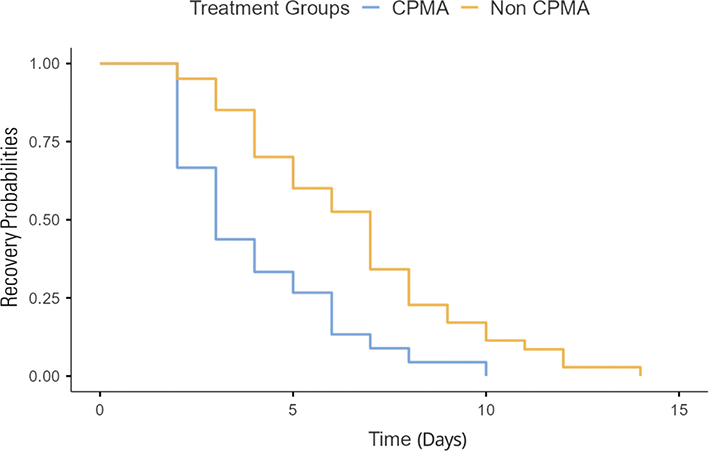

The median length of treatment for the CPMA group was significantly shorter than for the control group, with a p < 0.001 (Fig. 1). The median length of treatment for dogs treated with CPMA was 3 days (95% confidence interval, CI [3.3–4.5]) and the median length of treatment for the control group was 6.5 days (95% CI [5.5–7.4]). While the time to recovery curves were similar in shape, the curve for the CPMA group was shifted left indicating a quicker time to recovery, correlating with the median length of treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Length of Treatment of CPMA versus control dogs.

Fig. 2. Time to recovery of CPMA versus control dogs.

The daily cost of each potential treatment was calculated and applied to each case based on what treatments they received. Individual costs of treatment showed that the majority of the cost came from the hospitalization fees (Table 2).The overall cost of treatment for dogs treated with CPMA was significantly lower than the cost of treatment for the control group, with a p < 0.001 (Fig. 3). The average cost of treatment with CPMA versus and supportive care was $962 (95% CI [$848–$1,140]), versus $1,477 (95% CI [$1,243–$1,658]) for the dogs who were treated with supportive care alone. The cost of treatment compared to the length of treatment was evaluated and found to be directly linear as expected, since the cost of daily care comprises a large percentage of the total cost of treatment.

Fig. 3. Cost of treatment of CPMA treated dogs versus control dogs.

The CPMA group mortality rate was 6% (±3.3%), with 48 dogs who survived, one dog with an unassisted death, and two dogs who were euthanized. The control group mortality rate was 12% (±4.8%), with 38 dogs who survived treatment and five dogs who were euthanized. A Fisher’s exact test indicated no significant difference in mortality between the two treatment groups (Table 3). All dogs who survived treatment were ultimately adopted or redeemed by their owners.

Discussion

The addition of CPMA to this shelter’s established treatment plan was strongly correlated with a decreased length of treatment compared to dogs treated before CPMA was available. Other studies have also demonstrated that treatment with a CPMA decreases morbidity once infected with a CPV-2 viral strain.5,6 In a shelter setting, a decreased length of treatment contributes to a decreased overall length of stay, which has positive impacts on shelter cost, as well as the health and behavioral welfare of animals.8

In many shelters, financial resources are often a limiting factor in the ability to treat severe, emergent conditions such as canine parvovirus. Canine parvovirus can require minor outpatient treatment for a few days to lengthy hospital stays. Multiple treatments can add up quickly, and close examination of the trade-offs of expensive new therapies are critical for shelters who do treat canine parvovirus. For this shelter, the addition of CPMA actually led to a significant decrease in overall cost of treatment. We believe this is primarily due to the decreased length of treatment, but may also be attributed to decreased need for multiple adjunct treatments due to decreased severity and less staff time needed to give these treatments. This study did not compare the difference between how many individual treatments were prescribed between the CPMA treated dogs and those who were not treated with CPMA. It also did not compare the staff time dedicated to treatment between the two groups. These would be good areas to further investigate in order to determine if adding CPMA to treatment protocols is cost-effective for an individual shelter.

Left untreated, parvovirus infection is highly fatal to dogs, and even with treatment, fatalities still occur. Mortality of canine parvovirus with treatment has been reported anywhere from 10 to 25% and without treatment reported up to 91%.7,8,10,11 Early (pre-clinical) treatment with CPMA was shown in an industry study for USDA approval to decrease mortality of dogs infected with CPV-2.5 However, in that study, CPMA was used without other supportive treatments. This study showed a decreased percentage of dogs dying during treatment in the CPMA treated group, but it was not found to be statistically different from those treated before CPMA was used at this shelter. This may be partially due to the small number of dogs who died overall in both groups. Further investigation on mortality rates after the addition of CPMA to more standardized treatment plans may be beneficial to better determine if there is a significant effect.

One potential weakness in this study is that the supportive care treatment plans used in this shelter varied depending on individual veterinarian experiences and opinions. The shelter’s limited pharmacy stock, and a robust sample size likely limited this concern. Another weakness in this study is inherent in the retrospective before:after design of this natural experiment. Unperceived changes in patient population and shelter management over time may have had an effect on treatment duration, cost, and mortality between the two study groups. To our knowledge, no major shelter admission or management criteria changed during the short duration of time represented here (3 years). Finally, while there appeared to be no significant differences between the demographics of the control and the CPMA treated groups, there may have been some undetected effects of age, sex, and vaccination status on the length of treatment, cost of treatment, and mortality evaluated.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that the addition of CPMA to an established treatment program within a limited admission shelter was associated with a significantly decreased length of treatment and decreased overall treatment cost. For this shelter, using an expensive treatment such as CPMA was justified because it reduced the length and financial cost of treatment and time in the shelter. While a smaller number of dogs died with the addition of CPMA in this study, treatment did not significantly improve mortality.

Author contributions

Stefanie Hornback, DVM; Emmy Ferrell, DVM, MS, DABVP (SMP).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Oregon Humane Society for providing all the data reviewed, as well as Dr. Kirk Miller and Dr. Lena DeTar for writing and technical assistance.

Author notes

This abstract has been submitted for presentation at the 2026 ABVP annual conference.

References

| 1. | Mylonakis M, Kalli I, Rallis T. Canine Parvoviral Enteritis: An Update on the clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Vet Med Res Rep. 2016;7:91–100. doi: 10.2147/VMRR.S80971 |

| 2. | Goddard A, Leisewitz AL. Canine Parvovirus. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010;40(6):1041–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.07.007 |

| 3. | Crawford C. Canine and Feline Parvovirus in Animal Shelters. Presented at: Western Veterinary Conference. Las Vegas, NV; 2010. Accessed Aug 05, 2025. Available from: https://diasystemvet.se/documents/[Academic]%20Canine%20and%20Feline%20Parvovirus%20in%20Animal%20Shelters.pdf. |

| 4. | Pasteur K, Diana A, Yatcilla JK, Barnard S, Croney CC. Access to veterinary Care: Evaluating Working Definitions, Barriers, and Implications for Animal Welfare. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11:1335410. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1335410 |

| 5. | Larson L, Miller L, Margiasso M, et al. Early Administration of Canine Parvovirus Monoclonal Antibody Prevented Mortality after Experimental Challenge. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2024;262(4):506–512. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.09.0541 |

| 6. | Zhan H, Nguyen L, Ratcliff E, Chin R, Li S. US patent application No. 17/630,685. 2022. |

| 7. | Horecka K, Porter S, Amirian ES, Jefferson E. A Decade of Treatment of Canine Parvovirus in an Animal Shelter: A Retrospective Study. Animals. 2020;10(6):939. doi: 10.3390/ani10060939 |

| 8. | Perley K, Burns CC, Maguire C, et al. Retrospective Evaluation of Outpatient Canine Parvovirus Treatment in a Shelter-Based Low-Cost Urban Clinic. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2020;30(2):202–208. doi: 10.1111/vec.12941 |

| 9. | Herron ME, Kirby-Madden TM, Lord LK. Effects of environmental Enrichment on the Behavior of shelter Dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244(6):687–692. doi: 10.2460/javma.244.6.687 |

| 10. | Venn EC, Preisner K, Boscan PL, Twedt DC, Sullivan LA. Evaluation of an Outpatient Protocol in the Treatment of Canine Parvoviral Enteritis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2017;27(1):52–65. doi: 10.1111/vec.12561 |

| 11. | Ling M, Norris JM, Kelman M, Ward MP. Risk Factors for Death from Canine Parvoviral-Related Disease in Australia. Vet Microbiol. 2012;158(3–4):280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.02.034 |