SPECIAL ARTICLE

Cat Friendly (End-of-Life) Decision-Making

Euthanasia: how to avoid it and when to use it to support cat welfare

Vicky Halls and Claire Bessant

International Cat Care, Nadder Centre, Tisbury, Wiltshire, England

Keywords: euthanasia; end-of-life; quality of life; decision-making; unowned cats; welfare

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2025, 4: 156 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v4.156

Copyright: © 2025 Vicky Halls and Claire Bessant. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Published: 31 October 2025

This Cat Friendly decision-making document provides guidance on making confident and compassionate end-of-life decisions for cats which are in homing centres or coming through Trap, Neuter, Return (or Relocate; TNR) or community cat neutering programmes. The intended audience is anyone in any country working with, or interested in, unowned cats, principally in the context of cat homing centres (also referred to as shelters, rescues or adoption centres). The document will also be of interest to animal welfare organisations, those undertaking TNR or community cat neutering programmes and veterinary teams working in or with the unowned cat sector.

End-of-life decision-making is always challenging, but the difficult decision to end a life should only be made when there is a realisation of poor welfare, and euthanasia is the best available option for that individual. This is not the same as situations where cats are selected for euthanasia to reduce numbers (rather than because of their individual welfare state), which could be referred to as culling. Unfortunately, culling is a reality in many places both for free-roaming cats on the street and for some cats taken to homing centres. A confident and compassionate approach to decision-making requires homing centres to understand their responsibilities to staff and to cats. This document focuses on how cat quality of life in the homing centre environment can be improved and assessed and how compassionate end-of-life decisions can be made with confidence. The appendix looks at how to develop a cohesive approach to such decision-making and communicate it to staff and stakeholders.

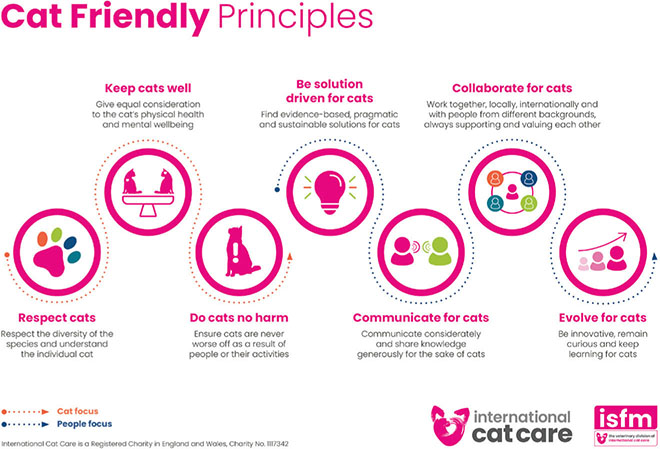

International Cat Care’s (iCatCare’s) series of Cat Friendly decision-making documents are intended to be plain-speaking guides to help those working with cats to navigate complex issues and to aid decision-making where nothing is black and white. They present respectful and carefully reasoned discussions bringing together:

- Available science

- Current practice

- Diversity of challenges faced by people working with cats

- Reflection of opinions, beliefs and practices to capture and acknowledge the ‘mood’ to help assess any approach required to improve cat welfare.

They are all underpinned by iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles (see above).

See the accompanying ‘Digest’ for an at-a-glance summary of the scope of the document. Note the word ‘cat’ refers to the domestic cat species Felis catus.

Globally, there are millions of unowned cats.

- Some live a solitary existence in uninhabited areas and are rarely seen

- Some live on the street and avoid human interaction. If neutered in TNR or community cat programmes, they may continue to live alongside the community without producing more cats or causing nuisance issues.

- Others are pet cats that have been abandoned, relinquished or have strayed and are taken in by homing organisations to try to find them new homes with people willing to adopt them.1

Cat numbers need to be managed for the welfare of both people and cats. How well this is done depends on many things; not the least of these is the quality of care provided by organisations/individuals set up to try and help them.

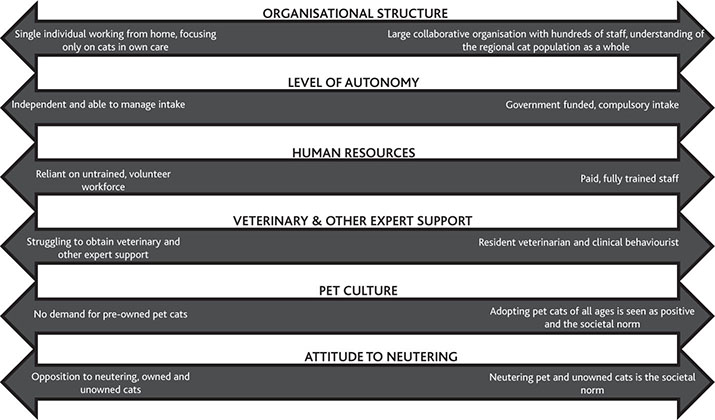

Around the world, there are many organisations trying to help unowned cats, and facilities, attitudes, expertise, funding, legalities and cultural influences vary considerably across the sector. The diagram illustrates the extremes, but there is a whole spectrum of organisational structures and circumstances in between.

The diverse range of organisations and circumstances in the unowned cat sector

Despite the diversity, all organisations aiming to help cats by undertaking TNR, community cat neutering programmes or running homing centres have responsibilities (including legal requirements in some countries) to each of the following:

- The community who lives alongside free-roaming street cats

- Staff and volunteers who put the aims of the organisation into action

- People who adopt cats

- Cats in contact with cats that have been homed (in terms of disease spread and conflict behaviour)

- The municipality or local authority responsible for removing unwanted cats (if the organisation has a contract or relationship with them)

- The organisation itself, in terms of its ethics and how it is perceived

- The organisation’s supporters (i.e. its volunteers and funders)

- Cats in TNR/community cat neutering programmes, especially in reference to:

- Cat welfare when trapping, transporting, storing and releasing cats

- Quality of veterinary care and neutering

- End-of-life decisions based on quality-of-life assessments for cats with poor welfare caused by injury or illness that cannot be managed without long confinement or ongoing treatment (which would require additional trapping)2,3

- Cats in the care of homing centres which must be kept in a way that ensures they do not suffer from being confined. In particular with reference to:

- Housing and handling to prevent them disease spread or injury

- Housing and handling to prevent negatively affecting mental well-being

- Identifying and meeting physical and emotional needs

- Finding homes for cats suitable to be adopted as pets by new owners

- Finding alternative outcomes for cats not able to live with people as pets

- Making decisions (which may include considering ending life) if cats cannot be helped within the scope of the organisation’s resources and expertise

All these areas can be managed to minimise the need for end-of-life decisions, but such decisions will still need to be made. The way this is done affects both cats and people.

End-of-life decision-making affects cats

- Cats suffer because end-of-life decisions are not made or are made too late because:

- Decision-makers cannot reach agreement and instead seek consensus in terms of people’s wishes, rather than considering what is in each cat’s best interests

- Decisions are not made at all, for fear of public backlash (e.g. the perception of ‘no kill’ being absolute)

- People are reluctant to contravene zero euthanasia laws or policies, which only allow decisions to end life for reasons of poor physical health (with no reference to an animal’s mental well-being)

- People do not feel confident or comfortable making decisions and so avoid doing so altogether

- There is a lack of access to euthanasia drugs/techniques/certified personnel

- Cats are euthanased because of a lack of alternative outcomes for those that do not cope well within the homing centre environment or cannot go to traditional pet homes

- Cats are euthanased because of excessive numbers, rather than for individual welfare reasons. This could be referred to as culling (sometimes called ‘convenience euthanasia’) and may happen in places where other aspects of cat population management, such as neutering programmes, are not in place, or few homes are available

- Cats are culled/euthanased in TNR or community cat neutering programmes because they cannot be returned or relocated for legal or other reasons

Methods of euthanasia

The International Companion Animal Management Coalition (ICAM) publication ‘The Welfare Basis for Euthanasia of Dogs and Cats and Policy Development’4 lists, among a great deal of information, advice and case studies, four primary criteria that ensure death caused by euthanasia/culling is humane:

- Pain and discomfort are minimised

- Rapid unconsciousness is followed by death

- Fear and distress are minimised

- The process is reliable and irreversible

There is information on euthanasia in ‘Methods for the Euthanasia of Dogs and Cats’ from the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA).5 Where possible (and where the drugs are available), injection of sodium pentobarbital should be the standard method for animal euthanasia. Unacceptable methods for euthanasia/culling in any animal shelter, according to the Humane Society of the United States,6 include carbon monoxide administration via a gas chamber, electrocution, drowning, gunshot, cervical dislocation, use of a decompression chamber, severing of the spinal cord and exsanguination (draining of blood).

Euthanasia should always be performed with compassion and using humane methods, and only when an animal’s welfare or quality of life cannot be improved.

End-of-life decision-making affects people

Cats cannot be cared for without people, and people are affected by what is happening to the cats. Good cat welfare is the top priority when running a homing organisation. For the staff and volunteers involved, the motivation is to help and save cats, and having an attachment to animals is an important part of the job.7 However, these very same people may be required to participate in end-of-life decisions and the process of euthanasia.

End-of-life decisions may be made by one person, may involve a veterinarian or behaviour expert, or may be the result of joint discussions. Euthanasia may be undertaken by a resident or visiting veterinarian or, in some circumstances, by appropriately trained non-veterinary personnel. Other staff may also be involved.

Research has shown that, in some circumstances, staff and volunteers may experience:

- ‘Moral stress’7 (causing feelings of failure, frustration, sadness and anger, as well as symptoms of burnout such as exhaustion and cynicism)

- ‘Compassion fatigue’8,9 (leading to stress and mental exhaustion)

- A phenomenon known as the ‘caring–killing paradox’10 (the strain of mutually inconsistent feelings connected with loving animals but also having to make end-of-life decisions)

- Guilt and self-blame after making end-of-life decisions, similar to pet owners who worry that they have made euthanasia decisions too early or too late11

- Distress because cats are euthanased but, equally, despair if suffering is ongoing, and a timely end-of-life decision is not made

- Anger and contempt towards decision-makers if they feel there is unfairness in the choice of which cats to euthanase or in the policy itself. For example, if cats staying with foster carers do not have their time outside the organisation count towards their length of stay when this is used as a parameter for end-of-life decision-making

- Frustration if they feel their insight, experience and views are not considered

- Upset because decisions may be based on behavioural assessments that they do not feel competent to undertake

- Anger and frustration at the local authority, and even the people on the board of their own organisation, if they are not seen to encourage more neutering, or oppose breeding of animals that can become excess to requirements – thus perpetuating the need for end-of-life decisions

A study that reviewed literature on euthanasia in homing organisations noted that the above sentiments and responses are now recognised by many who work within the unowned cat sector.12 The author of the study conducted focus group analyses, asking what people thought about how euthanasia affected what they actually did in their work. The findings suggest that not only does the actual process of euthanasia cause stress, but the decision-making that leads to ending a life is also highly stressful. For example, those having to make a decision based on behaviour may delay that decision in order to try very hard to change that cat’s behaviour to avoid an end-of-life outcome. However, lack of knowledge of how to assess the behaviour and quality of life of cats may hamper decisions and lead to frustration and feelings of helplessness. Likewise, frameworks or protocols aimed at making decisions easier may cause problems if they are introduced without discussion or relevance to the individual organisation.

All these studies underline the need for better understanding of cat quality of life in the homing centre environment and for help in assessing this. Providing hope by giving people ways to improve quality of life, so that they feel they have done as much as they can before end-of-life decisions may have to be made, could overcome some of the negative feelings associated with such decision-making. Factors that could affect the number and quality of end-of-life decisions that have to be made in a homing organisation include:

- Understanding quality of life

- Improving quality of life

- Acting on quality-of-life assessments

Factor 1: Understanding quality of life

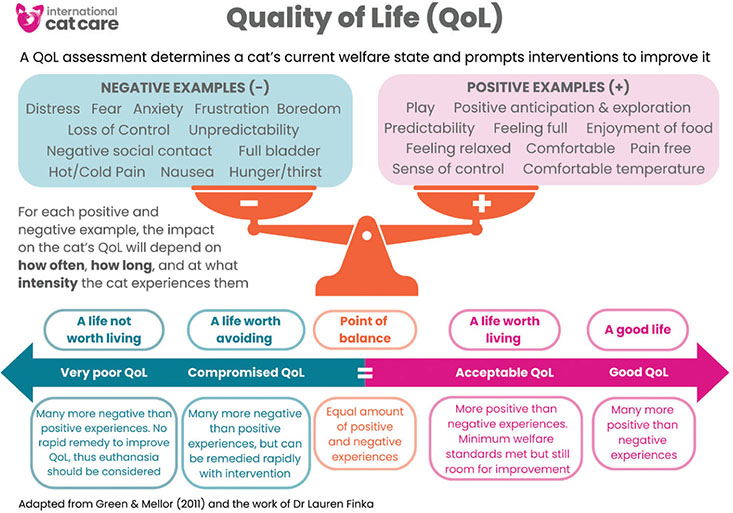

One of iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Principles is ‘Keep cats well – give equal consideration to the cat’s physical health and mental wellbeing’. Simply put, an animal’s quality of life can broadly be considered to be the feelings (physical and emotional) they experience in relation to the conditions in which they live and die. These can range from intense negative (bad or unpleasant) feelings to intense positive (good or pleasurable) feelings.13,14

Welfare is a scientific term, which, in the context of people working in homing centres, may be intuitively thought of by considering quality of life15 or even ‘a life worth living’ and looking at the balance of experiences the cat is trying to cope with (see diagram16).

Quality of life can be understood by looking at the balance of positive and negative experiences and emotions

Physical causes of poor quality of life

Cats’ inherent or natural behaviour is to be highly aware of their environment and to protect their vulnerability. They are masters of disguise when ill or in pain, and owners/carers need to recognise often subtle changes in behaviour or body language to appreciate that something is wrong. One paper reported that cat owners made euthanasia decisions later compared with dog owners,11 perhaps because cats are more likely to stay silent and out of sight, so their level of suffering may not be so evident.

A cat in a homing centre is in a strange and stressful place. Staff and volunteers may not have a relaxed ‘normal’ state of being for that individual cat against which to compare behaviour, making interpretation of suffering even more difficult. However, there are now excellent resources that describe how to recognise pain,17,18 and staff can develop their expertise. Veterinary input is vital, but veterinarians who work in or for homing organisations must understand the level of care that is practical and affordable and respect the care staff’s assessment of poor mental well-being that cannot be resolved in a cat. In turn, homing organisation staff and volunteers must respect the veterinarian’s assessment of the cat’s current or future health status.

Physical suffering in the period leading up to death should not be inevitable. When such suffering cannot be effectively reduced or prevented, humanely ending the life of the animal (i.e. euthanasia) must be considered. Probably the easiest end-of-life decision is one based on obvious physical suffering.

Mental causes of poor quality of life

The mental or emotional aspect of welfare is an additional dimension that must not be ignored simply because it is difficult to assess, or because acknowledging its presence means that tough decisions need to be made. In human medicine, the assessment of welfare incorporates negative feelings including fear, anxiety, sadness and depression, as well as the patient’s ability to cope. Consideration of these feelings (as far as we understand them) is now also included in the assessment of animal welfare.

Broom15 states that ‘Welfare measurements should be based on knowledge of the biology of the species and, in particular, on knowledge of the biology of the methods used by animals to try to cope with difficulties, of signs that coping attempts are failing and of indications of success in coping’.

In simple terms, for quality of life to be good, individual cats must be able to control their interactions with their surroundings and express their natural behaviours; this can be very difficult in a cage or pen. How each cat copes is determined by genes (i.e. characteristics inherited from parents), life experiences, physical health and mental well-being. Knowing how comfortable cats are with people can help to predict how they will cope with handling and their need for social contact.

If the cat’s mental well-being is reduced (e.g. animals are continually stressed because they have difficulty in coping with their environment15,19), this can also be considered poor welfare. People with training in cat behaviour can recognise stress or distress (see box). Often, for example, the simple observations of inactivity and quietness can point to a cat that is feeling overwhelmed with a situation or environment they cannot change or cope with.

What do we understand by stress and distress in cats?

Stress: A broad term to describe emotional and physiological responses to various experiences (both pleasant and unpleasant)

Acute stress response: An involuntary response to a perceived threat to aid survival, ie avoidance (flight), repulsion (fight), inhibition (freeze) and appeasement (fiddle)

Distress: A negative form of stress that has harmful effects when it is severe or prolonged and exceeds the coping ability of the individual.

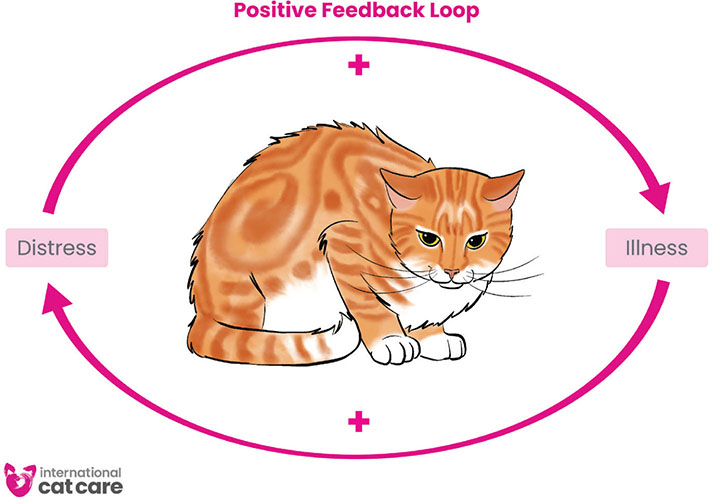

If a cat is distressed, this will potentially make everything feel much worse. Human research suggests that brain activity during psychological pain is similar to that occurring during physical pain; moreover, the pain of severe depression may be perceived as worse than any physical pain.20 Distressed cats can experience signs akin to behavioural depression; that is, a state of low mood, showing a lack of interest in their surroundings and things they previously liked. Cats confined in cages or pens for prolonged periods may become withdrawn and non-responsive. Poor mental well-being and distress are also associated with a reduced immune response and increased risk of disease (see diagram), thus leading to impaired physical health too.

It is always worth considering that cats ‘live in the moment’. They do not understand the motivations of humans keeping them confined today so they have a better chance at life tomorrow, and this needs to be considered when assessing quality of life. For example, keeping a cat in a cage for years, in the hope of providing a future life worth living, is not a good life now. Therefore, helping cats is not just about removing them from a ‘bad’ situation and placing them in ‘safe’ confinement. The quality of care they experience will impact their quality of life. Simply minimising or resolving negative physical or mental states is not sufficient for good welfare – there needs to be positive experiences too. Confinement has its place, but there are important limitations:

- Confining cats safely21,22 for as short a time as possible protects them from harm, disease and distress, giving them a greater chance of finding new homes

- Keeping cats in poor conditions for prolonged periods will reduce quality of life and increase the number of end-of-life decisions that must be made

In understanding what affects cat welfare and quality of life, the ‘Five Domains’ model’23 (see box) is a valuable framework that acknowledges both the physical health and the mental well-being of the animal and recognises that emotions and experiences impact as much on welfare as physical factors.

‘Five Domains’ of animal welfare

- Nutrition: Availability and quality of food and water

- Environment: Atmospheric and environmental conditions

- Health: Presence or absence of disease and injury

- Behaviour: Restriction or expression of behaviour

- Mental state: Subjective feelings and experiences

Factor 2: Improving quality of life

The quality of life of cats that enter homing centres, in terms of their physical and mental well-being, can improve or worsen, but, inevitably, keeping cats in a homing centre brings quality of life problems associated with confinement. The extent of the challenges will be influenced by the standard of care within the homing centre and the individual cat’s ability to cope with an unfamiliar environment and the proximity of people.

Generally, confinement can:

- Cause stress associated with being in a new, unfamiliar place

- Require cats to be in close proximity to people on a regular basis

- Result in cats being kept in overcrowded conditions that have a negative effect on their welfare,24,25 reducing food intake, causing weight loss and increasing susceptibility to catching diseases from other cats

- Cause distress by long-term exposure to things that the cat finds frightening but cannot escape from or control. Distress can be both physically harmful (compromising the immune system and making the cat less able to fight off infection) and mentally harmful (potentially leading to long-term psychological damage)

By far, the most effective ways to avoid having to make end-of-life decisions in homing centres are to ensure that:

- The right cats are taken into care in the first place

- The quality and safety of their confinement experience are optimised (and its longevity minimised)

- There is a clear plan for their future outcome

Things can be done to improve quality of life and thus reduce the number of end-of-life decisions that need to be made, and the ability of the homing organisation to assess itself and its processes realistically is pivotal. Genuine self-assessment can be challenging and painful because, although intentions are good, room for improvement is often found. An organisational review should consider whether it is possible to achieve the following:

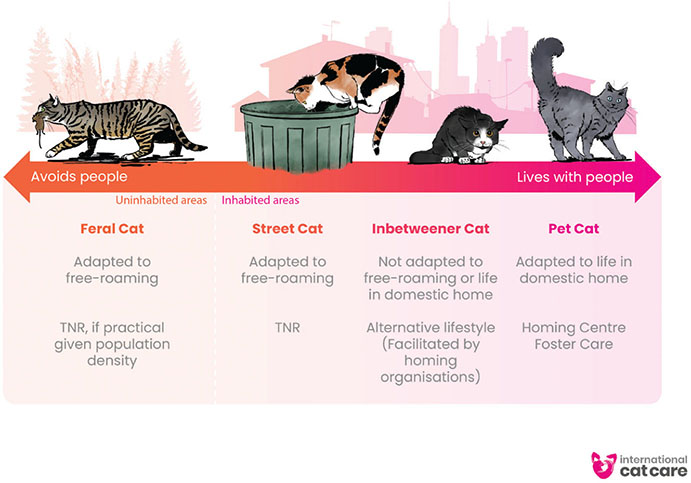

- Only take in cats which are likely to be comfortable around people, as the aim is to find them new homes. This means not admitting street or feral cats, which will be highly stressed by confinement and proximity of people. The range of lifestyles to which cats are adapted is shown below, along with preferred methods of helping them.1

- Limit intake to minimise overcrowding, and thus reduce the need for culling because of excessive numbers. Can ways be found to keep cats with their owners or in the community, or at least to stagger intake so that the homing centre can cope with the number of cats coming in and care for them properly? The Million Cat Challenge,26 iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Homing programme22 and recommendations in The Association of Shelter Medicine Veterinarians’ Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters27 all emphasise the need to assess and develop the organisation, starting with understanding its capacity to care (also referred to as the optimum occupancy), which involves a method for calculating how many cats can be cared for properly and provide ideas and ways to limit intake. Ultimately, by keeping more healthy and fewer distressed cats moving through the system more quickly, more cats can come in and be served well.

- Improve disease control, so that cats coming in do not become infected and become ill21

- Improve the environment with Cat Friendly housing; for example, with the inclusion of a hiding box in each cage or pen.28 Enriching the cage environment can also help to reduce distress caused by being unable to respond to the emotion of fear–anxiety

- Undertake community outreach to find more new homes. A programme in Australia that waived adoption fees to encourage adoptions and reduce culling of healthy adult cats in crowded shelters is an example of the potential of community outreach.29 A 3-day adoption drive, where cats over 1 year old were free to adopt, resulted in 137 cats being adopted (over five times the average number of weekly adoptions). There was concern that people attracted to free adoptions might be less responsible owners; however, no evidence was found for adverse outcomes associated with free adoptions.

- Remove barriers to finding new owners, including any personal prejudices and preferences held by the organisation’s staff and volunteers who may stop cats going to new homes

- Take a long-term view. In San Jose, California, a programme of giving out free neutering vouchers and reducing the intake of street and feral cats (by using TNR) led to successful reductions over 4 years in the number of kittens coming in, euthanasia rates and cases of upper respiratory disease (resulting from overcrowding and distress), as well as fewer dead cats on the street30

- Control intake through measures such as: having contracts with local animal control services or acting as a municipal shelter; limiting numbers coming from owners by only serving a specific area; or having reducing times when admissions can occur.

- Find a palliative care foster family or a new owner if the homing centre cannot afford to care long term for a sick cat where suffering does not yet outweigh the benefits of being alive (e.g. an elderly cat with chronic kidney disease)

- Find a foster carer experienced enough to assess a cat failing to cope in the homing centre in a less stressful environment and, at the same time, prevent a decline in quality of life associated with confinement within the homing centre

- Find an alternative lifestyle for ‘inbetweener’ cats, which are cats that have lived as pets, but not successfully, because they are uncomfortable to varying degrees with the proximity of people, and whose behaviour is seen as being unpredictable or unwelcome. This could be because they have not had sufficient or the right quality of interaction with people as young kittens or have a temperament trait that means they can become very frustrated with people. Equally, they are not able to live successfully as street cats because they require some support from people and may only feel comfortable if completely in control of the amount and type of interaction they have. iCatCare’s Cat Friendly decision-making paper on inbetweener cats suggests ways to recognise these cats and recommends possible outcomes for them31

- Return street or feral cats, with (by definition) poor quality of life if confined, to where they came from (‘Return to Field, Community Cat programme or Shelter, Neuter, Return’) or find new sites to relocate them

The lifestyle spectrum of the domestic cat

Cat Friendly Homing is a programme developed by International Cat Care, which looks at solutions for unowned pets. These are cats that are usually kept confined in a homing centre, in a cage or pen, or in a foster home with people who will care for them, prior to finding them a home. The programme explains the importance of

- Supporting both the physical health and mental well-being of the cats

- Recognising health problems when they arise and acting if help is required

- Understanding and implementing measures to prevent the spread of infectious diseases

- Caring for cats in a way that minimises any distress they might experience

- Interpreting whether cats are comfortable or uncomfortable with confinement and intervening to resolve distress

Factor 3: Making and acting on quality of life assessments

Cats are excellent at hiding physical and mental suffering, and so assessment of quality of life can be a challenge without the necessary training. In most circumstances, decisions can be improved if people are aware of cats’ needs and do not ignore the often-subtle signs. Understanding of welfare and quality of life from a cat’s point of view can make decision-making more logical and more compassionate.

However, people feel many emotions when confronted by animals without a home or suffering in some way, mainly reflecting a very human perspective of how they themselves would feel in that situation. People may feel compassion, motivating them to try to relieve any suffering. They may feel sympathetic and want to help. They may feel they are being empathetic (share the same feelings as the cat), although empathy is more complex because it relies on the ability to perceive, understand and care about the experiences or perspective of that animal.15,32

Respecting that cats are not humans may allow a more accurate appraisal of their quality of life. Actions that may make a person feel better (such as touching, giving attention and showing love) may not make the cat feel better if they cause pain or discomfort, or the cat is fearful of people or overwhelmed by a challenging setting. An understanding, empathetic, cat-centred approach may require education on the species and on how to assess whether the individual cat is coping in the homing centre. Most organisations do not have access to a behaviour expert and, therefore, need to develop their own expertise in assessing quality of life through training.

Practical approach to assessment

Quality of life assessment can be performed in different ways, such as by evaluating a cat’s behaviour and body language or undertaking measurements and tests of health. However, in the homing centre setting, even a simple approach to cat assessment can be very useful. The key issue to be addressed is welfare from the animal’s perspective, encompassing both physical health and mental well-being.15

Assessing a cat’s physical health may be difficult, but the input of a veterinarian can help to diagnose any health issues and give a prognosis for the cat. Assessing how well cats are coping with their present environment requires a different type of expertise that considers the cat ‘as a cat’. iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Homing programme suggests ways to understand and improve a cat’s quality of life.33,34 A practical tool developed specifically to assess how well an individual cat is coping with confinement in a homing centre is iCatCare’s ‘Traffic Light Assessment’ (TLA),35 which uses red, amber and green to indicate how distressing (or not) they are finding the experience (see diagram later). The system of colour coding can help staff to decide what to do and when, giving priority to the cats who need help the most. In essence, a cat’s TLA colour is used as a ‘call to action’ to ensure each cat is given the best possible care, and that no cat is ever overlooked.

The iCatCare Cat Friendly Homing TLA system showing how the colour denotes how well a cat is coping with confinement

The system aims to keep assessment simple so that it can be understood by everyone. In outline, assessment comprises:

- The cat’s physical health. A cat’s ability to cope in a challenging environment, such as a homing centre, is impacted by their physical health. Any improvement in health may enable them to cope better

- The cat’s background. Any relevant information about the cat’s background is collected and examined. For example, a cat with a life history of living indoors in one property may struggle with the dramatic and unprecedented change of circumstances when entering a homing centre

- Observation of the behaviour and body language displayed by the cat within the cage or pen. The ways in which individual cats show they are coping or not can vary from very active behaviour (e.g. scratching at the door and miaowing loudly) to something much more passive (e.g. excessive sleep, drowsy appearance or inactivity). Assessment of body posture and behaviour is covered in the training for iCatCare’s Cat Friendly Homing34,35

- Observation of the cat’s response to their carer’s presence. Some cats enjoy being with people and will be relaxed with them, given the right environment. Hence, housing and management need to be optimum so that cats have the best opportunity of showing that they are going to be comfortable with people, making it easier to find solutions for them living in homes. Street and feral cats fear people and should not be in homing centres, but even some cats that have been pets may not enjoy close human interaction. It should never be assumed that cats crave human company. The individual response to a carer’s presence can indicate the best outcome for each cat.

Acting on assessment results

Once the TLA colour has been determined, the cat is assigned an action plan that aims to find the right outcome for the cat as a matter of urgency. This may include:

- Discussing the individual cat with colleagues

- Changing the physical environment; for example, altering the layout of the cage or pen or adding extra resources

- Changing the social environment; for example, altering the level of interaction with the cat according to their needs

- Consulting a veterinarian to perform a pain assessment and develop a treatment protocol to address any health issues

- Considering foster care, if there is evidence to suggest this will allow cats to show their normal behaviour in a home environment

- Finding an alternative solution for cats identified as inbetweeners

- Neutering and ear-tipping any street or feral cats that have, despite intake protocols, entered the homing centre, and returning them to where they came from (or relocating them)

The following questions can help in decision-making regarding a cat’s current quality of life, and the quality of life it will have in the future (using the QoL tool described on page 8):

- Can this cat’s needs, based on the Five Domains, be fulfilled now or in the imminent future?

- What positive emotions or pleasure is this cat currently experiencing?

- Can this cat be provided with more opportunities to experience positive emotions/pleasure?

- What negative emotions or distress is this cat currently experiencing?

- Can things that cause the cat to experience negative emotions/distress be removed?

- How is the cat reacting to treatment (including efforts to administer the treatment), and is this in the best interests of the cat?

- Are there signs of improvement and interest in life?

- What is the likelihood that the cat will be adopted soon?

- What is the likelihood of good health in the short and long term?

Distinguishing between short-term and long-term quality of life may also help with decision-making. Cats may be saved in the short-term by taking them into the homing centre and providing them with any veterinary care they might need, but they may have a poor long-term welfare prognosis because they have other problems. If they continue to be treated, this may divert valuable resources (financial and otherwise) from animals with a higher likelihood of survival and a good quality of life. The concept of ‘sunk costs’ (i.e. money already spent) can be an additional complicating factor, making it more difficult to call a halt to treatment because it feels like previous effort and expenditure would be wasted.

For cats in a homing centre, decisions are not just required at the point of entry. Regular assessment of cats’ physical and mental well-being and their adoptability is vital. Cats may either settle in homing centres and cope (i.e. deal effectively with the difficult situation, their level of distress then reduces), or they remain distressed and fail to cope during their stay.

Having worked through the concept of quality of life and armed with an understanding that it must be assessed from the cat’s point of view, it is inevitable that in some cases, an unresolvable poor quality of life will be identified. If the organisation has reached this conclusion, given these considerations, that a cat has a life not worth living, and quality of life cannot be improved, then an end-of-life decision must be considered to prevent suffering (see box).

Making decisions that end in death can be hard. However, the alternative may be to tolerate or even condone suffering, which should be even less acceptable, particularly for an organisation set up to address poor welfare.

Examples of situations where end-of-life decisions need to be made

- Cats with serious health issues that are not treatable

- Cats not coping with life within the homing centre and with no options for foster care or potential adopters

- Long-stay cats with few prospects of being homed (e.g. because of temperament)

- No funds or insufficient staff or volunteers to care for cats properly

- Cats not suitable to be adopted and where there are no options for ‘Return to Field’

- Cats requiring costly long-term healthcare that nobody is willing to take on

- Cats that pose a danger/risk to new owners (through behaviour or ongoing disease)

- Cats with physical health and mental well-being issues associated with overcrowding that cannot be addressed

A benchmark for quality in the unowned cat sector

There are many things to consider in end-of-life scenarios, some practical, some ethical, some intellectual and some emotional. The responsibility for the prevention of suffering can be complex, and counterintuitive for some people if it results in death. Staff, volunteers and supporters (as well as critics) of organisations in the unowned cat sector may have different perceptions, beliefs and emotions, which affect how they feel and talk about end-of-life decisions, both publicly and privately. Development of a good policy or process (see Appendix 1) can bring understanding and a positive approach to the prevention of suffering, including euthanasia. The importance of education, collaboration and communication in imparting confidence that euthanasia has been performed well and in a fair manner cannot be underestimated.

Each homing centre needs to assess its resources and abilities realistically, understand cat welfare and quality of life, and be aware of the effects of pressures on its staff and volunteers. It will then be able to make consistent, fair and knowledgeable decisions about end-of-life situations because actions to improve quality of life have been undertaken and the ‘what-ifs’ are reduced. How the organisation deals with end-of-life decisions will be a benchmark for the quality of the organisation itself.

The depressing truth about reducing the number of end-of-life decisions is that unless the bigger picture is changed, excessive numbers of unwanted cats will continue to find their way onto the streets or to homing organisations. Making the right decisions for the cats in homing centres ensures prevention of suffering for some cats and enables new homes to be found for others. However, until widescale, collaborative and serious promotion of neutering for street cats, and especially for pet cats, is prioritised, there will be more and more unwanted litters, with many of these cats born to suffer.

KEY POINTS

- Confinement of cats in a homing centre brings quality of life challenges.

- Excessive numbers of unowned cats raise the risk of overcrowding, which is known to be damaging for cats both physically and mentally.

- Understanding cats and assessing quality of life from the cat’s point of view is vital.

- Improving quality of care can reduce the number of end-of-life decisions.

- For those working to help animals, end-of-life decisions can be the most difficult and distressing to make because they have formed relationships with the cats.

- Veterinary support and involvement are vital. The veterinarian must understand the limited resources of the organisation, and homing centre staff must respect veterinary expertise regarding a cat’s physical welfare.

- If veterinary and behavioural assessments point to poor cat welfare in the homing centre, the situation must be assessed realistically and honestly.

- Positive end-of-life decisions require clear thinking, objective analysis, an understanding of good quality of life and honest, transparent communication.

- Suffering will occur if end-of-life decisions are not made.

References

| 1. | Halls V, Bessant C. Managing Cat Populations Based on an Understanding of Cat Lifestyle and Population Dynamics. JSMCAH. 2023;2:58. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.58 |

| 2. | Alley Cat Allies. TNR Scenarios: How to Help Sick or Injured Cats. alleycat.org/community-cat-care/sick-or-injured-cats |

| 3. | Cats Protection. The Feral Guide. 2021. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. cats.org.uk/media/10267/feral-guide-cats-protection.pdf |

| 4. | ICAM. The Welfare Basis for Euthanasia of Dogs and Cats and Policy Development. International Companion Animal Management Coalition. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. icam-coalition.org/download/the-welfare-basis-for-the-euthanasia-of-dogs-and-cats-and-policy-development |

| 5. | Methods for the Euthanasia of Dogs and Cats: Comparison and Recommendations. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. icam-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Methods-for-the-euthanasia-of-dogs-and-cats-English.pdf. |

| 6. | The Humane Society of the United States. Euthanasia Reference Manual, 2013. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. humanepro.org/sites/default/files/documents/euthanasia-reference-manual.pdf. |

| 7. | Arluke A. Managing Emotions in an Animal Shelter. In: Manning A, Serpell J, eds. Animals and Human Society. Routledge; 1994:145–165. |

| 8. | Scotney RL, McLaughlin D, Keates HL. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Euthanasia and Occupational Stress in Personnel Working with Animals in Animal Shelters, Veterinary Clinics, and Biomedical Research Facilities. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2015;247:1121–1130. doi: 10.2460/javma.247.10.1121 |

| 9. | Andrukonis A, Hall NJ, Protopopova A. The Impact of Caring and Killing on Physiological and Psychometric Measures of Stress in Animal Shelter Employees: A Pilot Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9196. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249196. |

| 10. | Reeve CL, Rogelberg SG, Spitzmüller C, et al. The Caring-Killing Paradox: Euthanasia-Related Strain Among Animal-Shelter Workers. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;35:119–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02096.x |

| 11. | Vonk J, Bouma E, Dijkstra A. A Time to Say Goodbye: Empathy and Emotion Regulation Predict Timing of End-Of-Life Decisions By Pet Owners. HAI Bull. 2022;13:146–165. doi: 10.1079/hai.2022.0013. |

| 12. | Nguyen-Finn KL. Cost of Caring: The Effect of Euthanasia on Animal Shelter Workers. PhD dissertation. 2018. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. scholarworks.utrgv.edu/etd/321 |

| 13. | Weary DM. What is Suffering in Animals? In: Appleby MC, Weary DM, Sandøe P, eds. CABI Publishing, Dilemmas in Animal Welfare. 2014:188–202. |

| 14. | Broom DM. Assessing Welfare and Suffering. Behav Processes. 1991;25:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(91)90014-Q |

| 15. | Broom DM. Quality of Life Means Welfare: How is it Related to Other Concepts and Assessed? Anim Welfare. 2007;16:45–53. doi: 10.1017/S0962728600031729. |

| 16. | Green TV, Mellor D. Extending Ideas About Animal Welfare Assessment to Include ‘Quality Of Life’ and Related Concepts. N Z Vet J. 2011;59:263–271. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2011.610283. |

| 17. | Steagall PV, Monteiro BP. Acute Pain in Cats: Recent Advances in Clinical Assessment. J Feline Med Surg. 2019;21:25–34. doi: 10.1177/1098612X18808103. |

| 18. | Monteiro BP, Steagall PV. Chronic Pain in Cats: Recent Advances in Clinical Assessment. J Feline Med Surg. 2019;21:601–614. doi: 10.1177/1098612X19856179 |

| 19. | Yeates JW, Main DCJ. Assessment of Positive Welfare: A review. Vet J. 2008;175:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.05.009 |

| 20. | Mee S, Bunney BG, Reist C, et al. Psychological Pain: A Review of Evidence. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.03.003 |

| 21. | Karsten CL, Wagner DC, Kass PH, et al. An Observational Study on the Relationship Between Capacity for Care As An Animal Shelter Management Model and Cat Health, Adoption and Death in Three Animal Shelters. Vet J. 2017;227:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.08.003. |

| 22. | International Cat Care. Cat Friendly Homing: What are the Cat Friendly Solutions for Stray, Abandoned and Pet Cats? Accessed Sep 22, 2025. icatcare.org/resources/cat_friendly_homing_information_pack.pdf. |

| 23. | Mellor DJ. Operational Details of the Five Domains Models and Its Key Applications to the Assessment and Management of Animal Welfare. Animals. 2017;7:60. doi: 10.3390/ani7080060 |

| 24. | Koralesky KE, Rankin JM, Fraser D. Animal Sheltering: A Scoping Literature Review Grounded in Institutional Ethnography. Anim Welf. 2023;32. doi: 10.1017/awf.2022.4 |

| 25. | Turner P, Berry J, MacDonald S. Animal Shelters and Animal Welfare: Raising the Bar. Can Vet J. 2012;53:893–896. |

| 26. | Million Cat Challenge. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. millioncatchallenge.org. |

| 27. | The Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. Second edition. Journal of Shelter medicine and Community Animal Health; Vol. 1, S1. 2022. doi: 10.56771/ASVguidelines2022 |

| 28. | Ellis J, Stryhn H, Cockram MS. Effects of the Provision of a Hiding Box or Shelf on the Behaviour and Faecal Glucocorticoid Metabolites of Bold and Shy Cats Housed in Single Cages. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2021;236:105221. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105221 |

| 29. | Crawford HM, Fontaine JB, Calver MC. Using Free Adoptions to Reduce Crowding and Euthanasia at Cat Shelters: An Australian Case Study. Animals. 2017;7:92. doi: 10.3390/ani7120092. |

| 30. | Johnson KL, Cicirelli J. Study of the Effect on Cat Shelter Intakes and Euthanasia From a Shelter Return Project of 10,080 Cats from March 2010 to June 2014. Peer J. 2014;2. doi: 10.7717/peerj2:e646 |

| 31. | Halls V, Bessant C. Identifying solutions for ‘inbetweener’ cats. JSMCAH. 2023;2:59. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.59 |

| 32. | Advancing Conservation through Empathy for Wildlife. Empathy Glossary. aceforwildlife.org/empathy |

| 33. | International Cat Care. Care: Mental Wellbeing. iCatCare Cat Friendly Homing. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. https://icatcare.org/resources/cat_friendly_homing_information_pack.pdf. |

| 34. | International Cat Care. Care: Quality of Life Assessment. iCatCare Cat Friendly Homing. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. https://icatcare.org/resources/cat_friendly_homing_information_pack.pdf. |

| 35. | International Cat Care. Care: Traffic Light Assessment. iCatCare Cat Friendly Homing. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. https://icatcare.org/resources/cat_friendly_homing_information_pack.pdf. |

Appendix 1

Developing a cohesive approach to end-of-life decision-making

Understanding the difficulties surrounding end-of-life decisions, as outlined in this document, can help point to ways to develop a better approach. It is not possible for an end-of-life policy to cover every situation that arises in the complex world of cat welfare. However, there are certain principles that will enable the development of cohesive approach and policy, which can be shared and will reflect the ethos of the organisation. The following sections cover:

- The types of cats that the organisation deals with

- The needs of the community and community engagement

- A realistic appraisal of the organisation

- Understanding and supporting the people working there

- Developing an end-of-life policy

- Using and communicating the policy

The types of the cats that the organisation deals with

An organisation needs to know where cats that enter the centre come from, why cats are in care and why some are returned after adoption.1,2 New owner questionnaires or more pro-active approaches to information-gathering may need o be developed. Only by gathering relevant data and asking the right questions about cats coming in will it be possible to assess the problems in the area, provide a baseline against which to evaluate progress, and provide evidence should problems arise. For example:

- Is the organisation dealing mostly with relinquished pet cats?

- Is there an intake of street or feral cats?

- Does the centre take in cats from the local municipality or state-run shelter or pound?

- Do kittens come from unneutered pet cats or street cats?

- Is the free-roaming cat population in the area mostly healthy or are there signs of disease or injury?

The needs of the community and community engagement

Understanding and collaborating with the local community affects the success of cat population management programmes. Successful population management aims to treat cats humanely and address the issues that are of concern to people.3 It is vital to know how cats are viewed, what are the reasons for any complaints, do people neuter their pet cats and, if not, what are the barriers? If a homing centre is being considered in the area, is there a community of people willing to adopt adult, abandoned or relinquished cats? To what extent do people adopt cats versus taking in kittens off the street or going to breeders? Are there organisations involved in TNR (Trap, Neuter, Return) and pet neutering campaigns? Is the veterinary community involved?4 A paper5 that looked at community engagement in free-roaming cat control techniques found that the greatest control occurred with highest community engagement; education followed by adoption was the determining factor in the decreasing cat populations over time. Another paper6 concluded that controlling street cat populations is ineffective without comprehensive education in the regulation of domestic cat reproduction to prevent abandonment by pet owners. Community engagement can foster trust and can make people feel that they are contributing to local solutions for which they can provide local information or become involved in monitoring cats and supporting responsible pet cat ownership.

Realistic appraisal of the organisation

It is vital to appraise where the organisation is at present. This does not rule out ambition or planning for change, but the appraisal must be realistic to give a clear starting point. For example:

- What resources (e.g. space, time, staff, volunteers and funds) are available now?

- How long are cats staying in the homing centre and is this acceptable?

- Is overcrowding a problem all year round, or is the centre overwhelmed by lots of litters of young kittens during one season?

- What outcomes are being found for cats?

- Are further possible outcomes available and realistic?

- What expertise is available for assessing cats?

- How is good welfare prioritised for cats in the homing centre?

- What are the pressures the organisation faces?

- Could more be done with other organisations or in partnership with the local community?

Understanding and supporting the people working there

Homing organisations need motivated people – staff, volunteers, supporters and others, such as the veterinary team. They need to respect the contribution of each of these groups and understand the stresses involved in working in cat welfare. A good working atmosphere with an efficient and happy workforce requires transparency, fairness and trust in the decision-making process. Things that can help to overcome some of the issues raised by people working in the unowned cat sector include:

- Improving knowledge or expertise

- Showing involvement in the ‘bigger picture’

- Understanding public pressure

- Providing the right environment for euthanasia

- Gathering feedback and giving support

Improving knowledge or expertise

There may be a lack of knowledge or confidence in assessing cats’ quality of life. Training and continuous learning not only improve outcomes but also lead to better job satisfaction. One specific area that people are often left to fathom for themselves, based on their own understanding of compassion and empathy, is the assessment of quality of life. Recognising that it is quality of life from the cat’s point of view which is important, is fundamental. This may require extra learning and training – about cats in general, and about specific issues such as recognition of pain and stress or distress (particularly given that overt behaviour may be absent). Good veterinary advice is essential, always recognising that input from carers may be required to identify signs of stress or distress in individual cats. Many veterinarians could also benefit from learning more about cat behaviour.

Showing involvement in the bigger picture

The consequences of uncontrolled breeding directly impact the number of cats and kittens abandoned or given to homing organisations, and in some circumstances, the requirement for local authorities to control numbers. Homing organisations need to campaign for increased neutering of pet cats and well-structured humane cat population management for street and feral cats. They need to show their own staff, volunteers and supporters, as well as the wider public and government, that they understand and care about the causes of over-population. Better still, organisations need to be collaborating to bring more weight to their messaging.

This, of course, means that the organisation should not be homing any cats that are not neutered, certainly not cats of reproductive age. Many organisations now undertake neutering of kittens (prepubertal neutering) before homing, where the relevant veterinary expertise and knowledge is available, to ensure they will not be able to reproduce when old enough. In a 2023 study using a modelling approach, McDonald and colleagues7 reported that ‘Increased levels of prepubertal neutering resulted in reduced population growth, despite overall adult owned cat neutering prevalence remaining constant. The influence of prepubertal neutering in populations of cats with low overall neutering prevalence was particularly profound’. While this does not reflect the immediate situation everywhere, it does show the potential to develop a better future and will help those who work in the organisation to feel that something is being (or can be) done to stop the flow of cats.

Understanding public pressure

Public attitudes to end-of-life decisions and the publicity generated via social media may or may not be fair but do have consequences. Reactions to organisations, where culling is common, spurred the ‘no-kill’ movement (which campaigns to reduce the number of healthy or treatable animals being culled and restricts euthanasia to those animals only that face poor welfare) have been successful. Unfortunately, public attitudes are often not so strongly expressed when it comes to organisations that keep suffering animals alive or in overcrowded and highly stressful conditions, despite their best intentions. Also, there may be a risk that organisations might prevent appropriate euthanasia of cats with poor welfare for fear of misinterpretation, and because ‘no-kill’ has claimed the moral high ground. These pressures may be felt by staff, and open discussion within the organisation could help to work through how to understand and react to them.

Providing the right environment for euthanasia

Making sure there is time for euthanasia so that it is not rushed, and that the room is quiet and pleasant, is important in providing the right environment. Provision of quiet rooms for staff to recharge during the day may help and lets people know that they are understood and valued. Whether duties involving euthanasia are shared equally or undertaken by specifically trained people may depend on individuals and the organisation. It is important that those not directly involved in decision-making or carrying out euthanasia are not critical of others and do not undermine or blame them. More information is also available in the ASV Standards of Care in Animal Shelters.8

Gathering feedback and giving support

Encouraging feedback and providing ongoing support for staff involved in end-of-life decision-making and euthanasia will help to highlight where there are problems or trauma for people. This may take the form of debriefing groups and meetings, or support via counselling and non-judgemental professional help.

Developing an end-of-life policy

In order to develop a cohesive approach and policy, the organisation may choose to appoint a representative group of people to look at the issues discussed in this document. This might include a couple or more staff members as advocates and a veterinarian (if possible). They may also wish to bring in other advisers (e.g. behaviourists and ethicists) they trust for additional expertise, especially in countries and cultures where euthanasia is a particularly sensitive subject. This reduces the risk of biases and personal preferences and takes the focus off one person.

End-of-life decisions need to be made using all the information available about the organisation and in the light of discussions that have taken place on cat welfare and quality of life. Possibly, a group of staff advocates, veterinary experts, ethicists, policy developers and others may have spent a great deal of time discussing the details. Drawing up a specific policy or advice for staff may seem a daunting task, but looking at what is already available in terms of resources from other organisations can help. International Companion Animal Management Coalition’s (ICAM) document ‘The welfare basis for euthanasia of dogs and cats and policy development’9 contains a number of tools, including a decision algorithm produced by the International Fund for Animal Welfare and a decision matrix. The former is set of step-by-step instructions, linked by arrows and yes/no answers, to help reach the right conclusion; the latter is a tool used to evaluate and select the best option between different choices by listing values in rows and columns that help to identify and analyse different pieces of information. This may not be the way all organisations want to work, but these tools highlight criteria that need to be considered and can then be discussed.

Whichever approach is taken, it is important to check that outcomes and ideas align with how people work within the organisation. This helps to make sure that whatever is developed is useful and welcomed, rather than creating frustration. A small group could get together to help each other and test out the policy first, before putting it into daily use.

The organisation may additionally want to put together an ethics committee to assist the process, and/or to be an arbiter should disagreements occur. The aim, however, is for a cohesive approach; ideally, one where every end-of-life decision does not need to be questioned because people believe in the process and the assessors.

Using and communicating the policy

Even the best end-of-life decision-making policy can be divisive if it is not communicated successfully and perceived by staff and volunteers as being necessary and fair. Where it is recognised and accepted that everything has been done as well as possible, the organisation and individuals involved in drawing up the policy can be confident in the decisions and stand behind them. Crucially, they can let the wider organisation know that:

- Good cat welfare is of the utmost importance, and explain what this means in practice

- Serious consideration has been given to making the best end-of-life decisions

- People from across the organisation and other experts have been involved

- The aim is to use the policy or process fairly and consistently

- Feedback on the ‘useability’ of the policy or process will be welcomed and listened to

- Any problems will be discussed

The policy should be communicated to all existing staff and volunteers (even those not performing end-of-life decisions), and to potential new staff and volunteers before they start, so that they can take it into account in deciding whether to work with the organisation. If there are people who remain opposed to euthanasia for any reason, then the organisation may have to decide whether it still wishes to work with them.

In terms of wider communication, a clear statement can be put on the organisation’s website, available to everyone, to explain that euthanasia is a last resort for cats but is used positively to prevent suffering. The decision to end a cat’s life will always have been based on consultation with staff, advice from experts and best advice in the sector, and all other possible outcomes will have been explored before it is undertaken. More generally, the organisation may ask supporters to help with community outreach to find more adopters or to get the neutering message out widely to reduce the number of unwanted cats.

References

| 1. | Jensen JBH, Sandøe P, Nielsen SS. Owner-Related Reasons Matter More Than Behavioural Problems – A Study of Why Owners Relinquished Dogs and Cats to a Danish Animal Shelter From 1996 to 2017. Animals (Basel). 2020;10. doi: 10.3390/ani10061064 |

| 2. | Mundschau V, Suchak M. When and Why Cats Are Returned to Shelters. Animals (Basel). 2023;9:13. doi: 10.3390/ani13020243 |

| 3. | Halls V, Bessant C. Managing Cat Populations Based On An Understanding of Cat Lifestyle and Population Dynamics. JSMCAH. 2023;2. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.58 |

| 4. | Principles of Veterinary Community Engagement: First Edition 2024. Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health, 2024; 3(S2). doi: 10.56771/VCEprinciples.2024 |

| 5. | Ramírez Riveros D, González-Lagos C. Community Engagement and the Effectiveness of Free-Roaming Cat Control Techniques: A Systematic Review. 2024;14:492. doi: 10.3390/ani14030492 |

| 6. | Natoli E, Malandrucco L, Minati L, et al. Evaluation of Unowned Domestic Cat Management in the Urban Environment of Rome after 30 Years of Implementation of the No-Kill Policy (National and Regional Laws). Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:31. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00031 |

| 7. | McDonald J, Finka L, Foreman-Worsley R, et al. Cat: Empirical Modelling of Felis catus population dynamics in the UK. PLoS One 2023;18:e0287841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287841 |

| 8. | The Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. Second edition. Journal of Shelter medicine and Community Animal Health. 2022:Vol. 1, S1. doi: 10.56771/ASVguidelines.2022 |

| 9. | ICAM. The Welfare Basis for Euthanasia of Dogs and Cats and Policy Development. International Companion Animal Management Coalition. Accessed Sep 22, 2025. icam-coalition.org/download/the-welfare-basis-for-the-euthanasia-of-dogs-and-cats-and-policy-development. |