ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Sheltering Domestic Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Canada and the USA during the COVID-19 Pandemic and RHDV2 Emergence: A Cross-Sectional Mixed-Methods Survey of Intake, Care, and Management (2017–2022)

Carol E. Tinga1,2*, Jason B. Coe1 and Lee Niel1,2

1Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada; 2Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada

Abstract

Introduction: During the COVID-19 pandemic, news reports indicated increased numbers of stray rabbits and surrender requests at shelters and rabbit rescues. This study examined the impacts of the COVID-19 and Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2 (RHDV2) pandemics on rabbit intake, care, and management.

Methods: An online survey gathered a convenience sample of Canadian and American shelters and rabbit rescues. Retrospective data (2017–2022) were collected on rabbit intake numbers per year (all types, stray/abandoned only, and owner surrenders only). Nine categorical questions addressed practices related to capacity challenges, species-specific tracking, and whether RHDV2 affected intakes. Additional questions asked whether surrenders were declined, waiting lists were used, and if RHDV2 impacted intakes annually for each of 2017–2022. Participants also reported whether the COVID-19 pandemic affected their ability to care for domestic rabbits. Open-ended comments explored pandemic-related impacts; changes in stray, abandoned, or relinquished rabbits in 2022 vs. before; and any additional information about organizational roles in rabbit care. Analyses included descriptive statistics, multivariable regressions of intakes (point estimates, 95% confidence intervals, and exact P values), and thematic analysis.

Results: Organizations (N = 87) frequently used resource-intensive practices: foster care (94.3%), waiting lists (82.8%), and transfers in/out (78.2%, 75.9%) to other organizations. The proportion of organizations declining surrenders rose from 67.1% (55/82) in 2017 to 88.5% (77/87) in 2022; waiting lists rose from 59.0 (46/78) to 80.0% (68/85). COVID-19, RHDV2, and organization type were each associated with decreased intake across intake categories (all P < 0.05). A year-over-year decrease was observed only for stray/abandoned intakes in 2020 vs. 2021 (P = 0.0008). Thematic analysis revealed three COVID-19 effects: decreased intakes/adoptions, concurrent operational challenges including RHDV2, and sustained resource constraints.

Conclusion: Some organizations faced complex, simultaneous challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and RHDV2 emergence, significantly limiting intakes and straining resources. Recommendations include emergency planning, expanded fostering, and community partnerships to support sustainability and to safeguard rabbit welfare.

Keywords: animal abandonment; animal fostering; animal sheltering; animal relinquishment; companion animal welfare; companion rabbit; RHD; pandemics; pet rabbit; stray animals

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2026, 5: 153 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v5.153

Copyright: © 2026 Carol E. Tinga et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 15 August 2025; Revised: 31 October 2025; Accepted: 1 November 2025; Published: 5 January 2026

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest. Funders had no role in data collection, interpretation, or reporting.

This study received no external funding. The first author was supported during the research by an Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) PhD Entrance Scholarship, the Ethel Rose Charney Scholarship in the Human-Animal Bond, PhD supervisor L. Niel’s Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant, the Population Medicine Department’s general fund, and the University of Guelph COVID Student Stipend Support. The COVID-19 stipend was funded by the Office of Graduate and PostDoctoral Studies, the OVC, the Population Medicine Department, and L. Niel’s NSERC grant. Postdoctoral support for publication was provided through the OVC’s Marion and Herb Hallatt Beau Valley Professorship held by L. Niel, in support of human-animal bond science.

Correspondence: *Carol E. Tinga, Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, 50 Stone Rd E, Guelph, Ontario N1G 2W1, Canada. Tel: +1 519-766-2728. Email: tingac@uoguelph.ca

Reviewers: Clare Ellis, Emily McCobb

Supplementary material: Supplementary material for this article can be accessed here.

Despite being described as friendly, playful,1 and intelligent,2 companion rabbits may be relinquished, abandoned, or become strays, requiring rehoming in Canada3 and the USA,4 per studies predating the COVID-19 pandemic. Unwanted rabbits in shelters may be euthanized at shelters on intake (sometimes at the request of owners) or later on.4,5 While some rabbits end up in shelters in Canada3 and the USA,4 reports from other countries suggest that many shelters have limited rabbit capacity – some prioritize dogs and cats,6,7 some do not accept rabbits,8 and others lack proper facilities.6 In receptive shelters, rabbits may be housed on-site and/or fostered by volunteers until adoption.4 Foster-based rabbit rescues (e.g. Los Angeles Rabbit Foundation9) may also be involved. Rabbits can also be rehomed directly by owners via online ads, as reported in the UK10 and Sweden.8 Prior studies3,4,11,12 have not reported data on declined surrender requests or waiting lists.

After COVID-19 was declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020,13 people were asked to comply with public health recommendations, including social distancing and lockdowns. Lockdowns were location-dependent in Canada14 and the USA,15 and reopening began about 1.5 months earlier in the USA in the first phase of the pandemic.16 In the USA, animal control officers provided restricted services, e.g. responding only to high-priority and emergency calls and reducing non-essential intakes.17 In Canada, day-to-day operations at shelters were limited.18 In 2021, Canadian news sources reported increased rabbit abandonment and relinquishment at animal shelters and rabbit rescues, possibly because owners were unprepared for the time, work, and space that rabbits need; unexpected litters; and decreased access to veterinary care.19,20,21 Similar reports emerged in the USA in 2022.22,23 Also concerning during this period was Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (type) 2 (RHDV2), a virus affecting domestic and wild rabbits that was first detected in France in 201024,25 and rapidly spread worldwide.26,27 RHDV2 was first detected in eastern Canada (Quebec) in 2016, then in eastern USA (Ohio), and western Canada (British Columbia (BC)) in 2018.26,27 Preventing this high-consequence pathogen requires extensive biosecurity.28,29

While some studies are available that describe unwanted domestic rabbits taken in over limited geographical areas by shelters or rabbit rescues,3,4,6,11,12 a wider-ranging geographic and organization type assessment of management practices, intake, and personnel’s perceptions has not been undertaken. The impact of COVID-19 and RDHV2 on shelters and rabbit rescues caring for domestic rabbits remains largely unknown, although both are hypothesized to have reduced rabbit intakes in BC shelters between 2017 and 2021.12 Our objectives were to describe domestic rabbit management practices related to capacity, changes in rabbit intakes (all types, stray/abandoned only, and owner surrenders only) in Canada and the USA from 2017 to 2022, and organizational resilience to the COVID-19 and RHDV2 challenges during this time.

Methods

Recruitment

A total of 459 humane organizations were contacted, including national and provincial/territorial/state-level bodies representing both shelters (e.g. 4 shelters per US state and 125 Humane Society and Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals shelters in Canada) and rabbit rescues (e.g. 95 House Rabbit Society and rabbit rescue groups in the USA and 21 rabbit and exotic/small animal rescues in Canada). Initial outreach was conducted online, with additional contact at a shelter administrator conference in Ontario, Canada. All organizations were asked to complete the survey and/or share the survey link. Anyone representing an organization could complete the questionnaire. Participants were asked to ‘Ensure that only one survey is completed for the organization to prevent duplication of responses’.

Data collection

An anonymous, English, voluntary, incentive-free, 10-min open survey (Supplementary material – survey) was developed in Qualtrics (version XM, Provo, UT) using a convergent, single-phase design. It was available from August 25, 2022, to January 4, 2023. The survey included previously developed3,4,11 and new items (total: 17–55, depending on applicability). After providing consent, participating organizations proceeded to the inclusion criteria (i.e. take in stray, abandoned, and/or owner-surrendered rabbits; based in Canada or USA) and then organization type (e.g. shelter and rabbit rescue) and location. Subsequent items collected yes/no/prefer not to say responses about domestic rabbit management practices (animal control contracts, personnel pick up strays, foster care, organization transfers rabbits in from other organizations, organization transfers rabbits out to other organizations, euthanasia of healthy rabbits, declining owner surrenders, intake waiting list, record rabbit intakes separate from other species’ intakes) and if RHDV2 affected intakes. Numerical intake data were collected for 2017–2022 (all types, stray/abandoned only, and owner surrenders only) and the number of months submitted for 2022. Yes/no/unsure/not applicable responses for declining owner surrenders, having a waiting list, and if RHDV2 affected rabbit intake for each of the 6 years sampled were collected, and yes/no responses to whether COVID-19 affected the ability to care for domestic rabbits. The survey concluded with three open-ended items: (1) how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the ability to care for domestic rabbits (if applicable); (2) differences seen in rabbits found stray or abandoned, or being relinquished in 2022 compared to before (e.g. younger, more behavior issues); and (3) any additional information about domestic rabbits and the organization’s role in caring for them.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics

Results (frequency and percentage) for organization type, location, rabbit management practices, RHDV2, and COVID-19 impacts, and for declining owner surrenders, waiting lists, and RHDV2 impact by year were computed in SAS OnDemand for Academics (Release 3.81; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) using PROC FREQ. Rabbit intakes (count, percentage, mean, standard deviation, median, mode, and range) were computed using PROC UNIVARIATE.

Modeling intakes

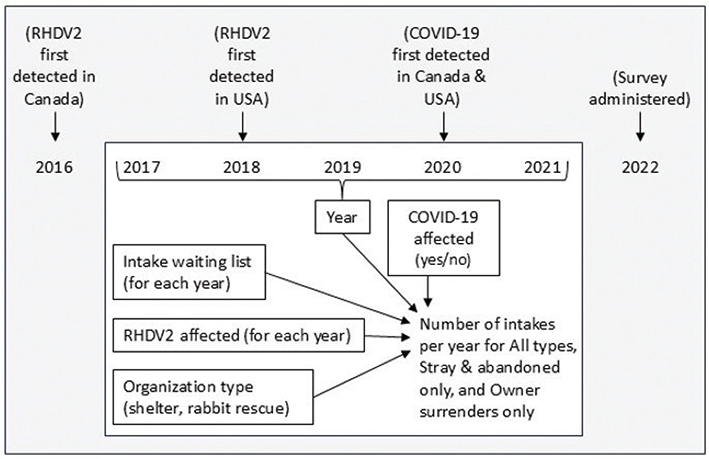

Three intake outcomes in three separate models were explored using SAS: (1) all types, (2) stray/abandoned only, and (3) owner surrenders only (see Fig. 1). Manual, stepwise modeling was used to explore relationships between fixed effects: year (2017–2021), rabbit care affected by COVID-19 (yes/no), organization type (shelter/rabbit rescue), and yes/no indicators for waiting list and RHDV2 impact (by year for both). Organization nested within organization type was treated as a random effect. Generalized linear mixed models (PROC GLIMMIX) were used to analyze annual rabbit intake rates, using only complete datasets for each intake category.

Fig. 1. Path model showing timing of key events and available data for potential explanatory factors (year, COVID-19 affected, [have intake] waiting list, RHDV2 affected, and organization type) used in modeling annual domestic rabbit intakes (all types, stray and abandoned only, and owner surrenders only).

Model fit was assessed by determining whether a Poisson or negative binomial (NB) model was more appropriate for each main effects model: (1) generalized χ2/degrees of freedom much >1 suggested NB, and (2) a significant overdispersion scale estimate supported NB. Organizations nested within organization type were repeated measures over time, so repeated measure approaches were attempted. All main effects of explanatory variables were modeled as categorical for 2017–2021.

Manual forward and backward stepwise modeling were used, and 2- and 3-way interactions were tested for effect modification. Previously eliminated variables (P > 0.05) were retried. Rates with approximate 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and rate ratios, P values, and 95% CIs for pairwise tests are reported. If year remained a main effect in a final model, Tukey-adjusted P values and 95% CIs were reported. Pearson residuals were plotted against predicted values, and included/excluded variables were checked for model issues or patterns suggesting missing variables. As the 2022 data were incomplete and monthly intake rates might not be constant, 2022 was excluded from modeling.

Qualitative analysis of comments

The first author conducted a thematic analysis using NVivo (Release 1.7.1, www.lumivero.com) and coded all available responses descriptively using a data-driven, inductive, iterative approach.30–32 Coding, themes, and subthemes were reviewed with coauthors. Participants were numbered 1–87 (e.g. participant 3: [P3]).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Participants (N = 87) were usually from shelters, with two thirds from Canada-based organizations (Table 1). Most Canadian organizations were shelters (55/59, 93.2%), whereas American organizations were more diverse (shelters: 15/28, 53.6%; rabbit rescues: 13/28, 46.4%). About one third of participants reported having an animal control contract.

| Variable | Response categorya | Frequency | Percentage |

| Organization type | Shelterb | 70 | 80.5 |

| Rabbit rescuec | 17 | 19.5 | |

| Location | Canadad | 59 | 67.8 |

| USAe | 28 | 32.2 | |

| Animal control contract with another organization (e.g. municipal or state animal agency) | Yes | 27 | 31.0 |

| No | 60 | 69.0 | |

| Personnel (e.g. staff, volunteers) pick up stray domestic rabbits | Yes | 68 | 78.2 |

| No | 19 | 21.8 | |

| Coordinate foster care for rabbits | Yes | 82 | 94.3 |

| No | 5 | 5.8 | |

| Organization transfers domestic rabbits in from other organizations | Yes | 68 | 78.2 |

| No | 19 | 21.8 | |

| Organization transfers domestic rabbits out to other organizations | Yes | 66 | 75.9 |

| No | 21 | 24.1 | |

| Organization euthanizes healthy rabbits | Yes | 2 | 2.3 |

| No | 85 | 97.7 | |

| Ever had to turn away surrender requests because at capacity for sheltering, fostering, or rehoming domestic rabbits | Yes | 78 | 89.7 |

| No | 8 | 9.2 | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Waiting list available | Yes | 72 | 82.8 |

| No | 13 | 14.9 | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 2.3 | |

| Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2 (RHDV2) affected organization’s ability to take in rabbits | Yes | 52 | 59.8 |

| No | 34 | 39.1 | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 1.2 | |

| COVID-19 pandemic affected organization’s ability to care for domestic rabbits | Yes | 57 | 65.5 |

| No | 30 | 34.5 | |

| Organization records the number of domestic rabbits taken in separately from number of other species taken in | Yes | 75 | 86.2 |

| No | 9 | 10.3 | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 3.5 | |

| a‘Prefer not to say’ was offered for all items except Organization type, Location, and COVID-19 variable. bSurvey category: ‘Organization has a broad species focus (e.g. animal shelter, animal rescue, humane society) that includes taking in stray, abandoned, and/or owner surrendered domestic rabbits’. cSurvey category: ‘Rabbit-focused organization (e.g. rabbit rescue, rabbit society, rabbit charity) that takes in stray, abandoned, and/or owner-surrendered domestic rabbits’. dBC (35); ON (16); AB (3); MB (2); NB, NL, and QC (1 each). eCA (4); VT (3); GA, IL, NC, and WA (2 each); CO, FL, IN, KS, LA, MI, MN, MT, NY, OR, PA, SD, and UT (1 each). |

|||

Organizations commonly used resource-intensive practices (e.g. picking up strays, transferring rabbits between organizations, coordinating foster care, and waiting lists), and owner surrenders were often declined. Personnel picked up strays in both countries, and this practice was more common at rabbit rescues (15/17, 88.2%) than shelters (53/70, 75.7%). Four shelters and one rabbit rescue did not coordinate foster care. Reports of euthanizing healthy rabbits were rare. At survey completion, most organizations (89.7%) had turned away surrenders; however, one rabbit rescue and seven shelters had not. From 2017 to 2022 (the latter, a partial reporting year), the number and proportion of organizations turning surrenders away rose, while those that had not or were unsure fell (Table 2a). Similarly, most organizations had a waiting list for surrendering rabbits at survey completion (Table 1), with increases from 2017 to 2022 as the number unsure or without one fell (Table 2b).

| Year | Number of responses (%)b | ||||

| Yes | No | Unsure | Prefer not to sayc | nd | |

| (a) Organizations turning away people wanting to surrender rabbits | |||||

| 2017 | 55 (67.1%) | 14 (17.1%) | 12 (14.6%) | 1 (1.2%) | 82 |

| 2018 | 56 (67.5%) | 13 (15.7%) | 13 (15.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | 83 |

| 2019 | 61 (73.5%) | 15 (18.1%) | 6 (7.2%) | 1 (1.2%) | 83 |

| 2020 | 67 (77.9%) | 14 (16.3%) | 4 (4.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | 86 |

| 2021 | 75 (86.2%) | 8 (9.2%) | 3 (3.4%) | 1 (1.1%) | 87 |

| 2022a | 77 (88.5%) | 8 (9.2%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 87 |

| (b) Organizations with an intake waiting list for rabbits | |||||

| 2017 | 46 (59.0%) | 18 (23.1%) | 12 (15.4%) | 2 (2.6%) | 78 |

| 2018 | 48 (60.8%) | 17 (21.5%) | 12 (15.2%) | 2 (2.5%) | 79 |

| 2019 | 50 (63.3%) | 18 (22.8%) | 9 (11.4%) | 2 (2.5%) | 79 |

| 2020 | 57 (70.4%) | 16 (19.8%) | 6 (7.4%) | 2 (2.5%) | 81 |

| 2021 | 66 (78.6%) | 15 (17.9%) | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (2.4%) | 84 |

| 2022a | 68 (80.0%) | 14 (16.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | 2 (2.4%) | 85 |

| (c) Organizations whose ability to take in domestic rabbits that were affected by RHDV2 | |||||

| 2017 | 0 (0%) | 79 (97.5%) | 2 (2.5%) | - | 81 |

| 2018 | 35 (43.2%) | 44 (54.3%) | 2 (2.5%) | - | 81 |

| 2019 | 33 (40.7%) | 45 (55.6%) | 3 (3.7%) | - | 81 |

| 2020 | 39 (47.0%) | 42 (50.6%) | 2 (2.4%) | - | 83 |

| 2021 | 43 (50.6%) | 41 (48.2%) | 1 (1.2%) | - | 85 |

| 2022a | 52 (59.8%) | 34 (39.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | - | 87 |

| Abbreviations: n, sample size; RHDV2, Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (type) 2. aIncomplete year of data collection. bIf an organization did not exist in a particular year, they were instructed to answer ‘Not applicable’ for that year. These responses were automatically excluded from the Qualtrics data and were unavailable for analysis. cResponse choice not offered for 2022. dParticipants who answered ‘Yes’ to the initial yes/no/unsure/not applicable questions (turn away owner surrenders, have a waiting list, RHDV2 affected ability to take in domestic rabbits) were asked for year-by-year details, but missing data meant N = 87 was not reached for each row. |

|||||

At survey completion, 60% of organizations said RHDV2 affected their ability to take in rabbits (Table 1). Most were in Canada (41/52, 78.8%) in three provinces, although nine US states were also affected. Similar proportions of rabbit rescues (10/17, 58.8%) and shelters (42/70, 60.0%) reported impacts. No organizations were affected in 2017, but numbers appear to increase from 2018 to 2022 (Table 2c).

Two-thirds of organizations reported that COVID-19 had affected their organization’s ability to care for domestic rabbits (Table 1), with similar proportions among shelters (46/70, 65.7%) and rabbit rescues (11/17, 64.7%). Most impacted organizations were shelters (46/57, 80.7%) and were based in Canada (45/57, 78.9%).

Most organizations recorded domestic rabbit intakes separately from other species (Table 1). Intake data varied widely, and the number of organizations reporting annual data was inconsistent across intake types (Table 3a–c), making year-to-year comparisons (e.g. rabbits/month/organization averages) inadvisable. For 2020, ‘0’ rabbits was the most frequent all-types intake response (n = 7). ‘0’ intakes were more frequent for stray and abandoned rabbits: organizations taking none doubled in 2019–2020 (n = 14) compared to 2017–2018 (n = 6–7). At least 18.0% of organizations did not take owner surrenders in any given year. The highest proportion (37.9%) was in 2022, and proportions appeared to increase over time. The 2022 data (n = 73) covered only 4–11 months per organization (e.g. 4 months: January–April). Despite the limited data, many rabbit intakes were still reported for the all-types category, while large numbers of organizations reported they were not taking in any stray and abandoned rabbits (17/65, 26.2%) or owner surrenders (25/66, 37.9%).

| Yeara | Number of organizations | Number of rabbitsd | Mean | SD | Median | Mode | Range | Number of organizations (%) taking in no rabbits |

| (a) All types of domestic rabbit intakesb | ||||||||

| 2017 | 66 | 4,369 | 66.2 | 102.7 | 22.5 | 6 | 0–476 | 2 (3.0%) |

| 2018 | 67 | 3,788 | 56.5 | 81.4 | 17.0 | 5 | 0–339 | 1 (1.5%) |

| 2019 | 71 | 4,419 | 62.2 | 90.8 | 20.0 | 1 | 0–437 | 3 (4.2%) |

| 2020 | 70 | 3,436 | 49.1 | 69.0 | 15.0 | 0 | 0–332 | 7 (10.0%) |

| 2021 | 70 | 4,310 | 61.6 | 90.0 | 20.0 | 2 | 0–393 | 2 (2.9%) |

| 2022c | 71 | 3,627 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 (5.6%) |

| (b) Stray and abandoned rabbits only | ||||||||

| 2017 | 61 | 2,039 | 33.4 | 82.6 | 9.0 | 0 | 0–600e | 7 (11.5%) |

| 2018 | 60 | 1,866 | 31.1 | 89.0 | 5.0 | 1 | 0–650e | 6 (10.0%) |

| 2019 | 63 | 2,339 | 37.1 | 97.7 | 6.0 | 0 | 0–700e | 14 (22.2%) |

| 2020 | 63 | 2,051 | 32.6 | 94.9 | 4.0 | 0 | 0–700e | 14 (22.2%) |

| 2021 | 64 | 2,607 | 40.7 | 99.3 | 7.0 | 0 | 0–725e | 9 (14.1%) |

| 2022c | 65 | 1,662 | - | - | - | - | 17 (26.2%) | |

| (c) Owner surrenders only (excluding adoption returns) | ||||||||

| 2017 | 62 | 1,517 | 24.5 | 45.1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0–249 | 12 (19.4%) |

| 2018 | 61 | 1,464 | 24.0 | 43.0 | 3.0 | 1 | 0–202 | 11 (18.0%) |

| 2019 | 63 | 1,664 | 26.4 | 44.9 | 6.0 | 0 | 0–197 | 14 (22.3%) |

| 2020 | 64 | 1,297 | 20.3 | 33.8 | 5.5 | 0 | 0–150 | 17 (26.6%) |

| 2021 | 64 | 1,334 | 20.8 | 42.6 | 4.5 | 0 | 0–246 | 16 (25.0%) |

| 2022c | 66 | 1,068 | - | - | - | - | - | 25 (37.9%) |

| Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation. a‘Not applicable’ was an option for 2017–2021 but not 2022. These responses were unavailable in the Qualtrics export and for analysis. b‘e.g. born on site, stray, abandoned, owner surrender, adoption return, confiscated, transferred from another organization’. c2022 was an incomplete year of data collection (n = 73; mean, median, mode: 9 months; standard deviation 1 month; range 4–11 months). d4–5 organization ([P4], [P5], [P9], [P37], and [P54]) may have rounded intake numbers for each category. eThese maximums are for a rabbit rescue that did not report all types of intakes or owner surrenders. |

||||||||

Modeling intakes

For all three outcomes, a random effect of organization nested within organization type was necessary, and an NB model was a better fit than a Poisson model for a full main effects only (year, COVID-19, organization type, waiting list, and RHDV2) model. No interactions were significant at P < 0.05 during backwards eliminations. Estimates of intake rates and their 95% CIs are summarized in Table 4, and modeling results are shown in Table 5. Residual analyses suggest model assumptions were adequately met. Models with repeated measures did not converge properly, so results are not reported.

| Potential explanatory variable | Rate | 95% CI |

| (a) All typesa (n = 65) | ||

| Shelter | 24.8 | 17.2, 35.7 |

| Rabbit rescue | 122.6 | 43.4, 346.4 |

| RHDV2 affected | 43.4 | 24.3, 77.5 |

| Not RHDV2 affected | 69.9 | 39.9, 122.7 |

| COVID-19 affected | 33.3 | 19.3, 57.5 |

| Not COVID-19 affected | 91.1 | 42.5, 195.6 |

| (b) Stray and abandoned rabbits only (n = 61) | ||

| 2017 | 25.6 | 11.8, 55.4 |

| 2018 | 29.6 | 14.2, 61.5 |

| 2019 | 28.5 | 13.8, 59.1 |

| 2020 | 23.6 | 11.4, 48.8 |

| 2021 | 39.5 | 19.2, 81.1 |

| Shelter | 7.0 | 4.5, 11.1 |

| Rabbit rescue | 118.4 | 31.4, 446.8 |

| RHDV2 affected | 19.8 | 9.3, 42.3 |

| Not RHDV2 affected | 42.2 | 20.8, 85.6 |

| COVID-19 affected | 18.6 | 9.3, 37.4 |

| Not COVID-19 affected | 44.8 | 17.2, 116.4 |

| (c) Owner surrenders only (excluding adoption returns) (n = 59) | ||

| Shelter | 7.4 | 4.6, 11.8 |

| Rabbit rescue | 36.2 | 7.9, 166.2 |

| RHDV2 affected | 12.5 | 5.4, 29.1 |

| Not RHDV2 affected | 21.2 | 9.5, 47.4 |

| COVID-19 affected | 7.6 | 3.4, 16.9 |

| Not COVID-19 affected | 35.1 | 12.5, 98.3 |

| Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; n, sample size. a‘e.g. born on site, stray, abandoned, owner surrender, adoption return, confiscated, transferred from another organization’. |

||

| Potential explanatory variable | P value | Adj. P value | Adj. LL | LL | Rate ratio | UL | Adj. UL |

| (a) All typesa (n = 65) | |||||||

| Rabbit rescue/Shelter | 0.0038 | 1.71 | 4.95 | 14.33 | |||

| Not RHDV2 affected/RHDV2 affected | < 0.0001 | 1.31 | 1.61 | 1.98 | |||

| Not COVID-19 affected/COVID-19 affected | 0.0055 | 1.35 | 2.73 | 5.54 | |||

| (b) Stray and abandoned rabbits only (n = 61) | |||||||

| Overall year effect | 0.0019 | ||||||

| 2017/2018 | 0.40 | 0.91 | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.87 | 1.21 | 1.38 |

| 2017/2019 | 0.50 | 0.96 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 1.23 | 1.39 |

| 2017/2020 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 1.51 | 1.72 |

| 2017/2021 | 0.0093 | 0.070 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 1.02 |

| 2018/2019 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 1.04 | 1.36 | 1.52 |

| 2018/2020 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 1.25 | 1.65 | 1.84 |

| 2018/2021 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.75 | 0.98 | 1.09 |

| 2019/2020 | 0.15 | 0.61 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 1.21 | 1.57 | 1.74 |

| 2019/2021 | 0.013 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 1.03 |

| 2020/2021 | < 0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.85 |

| Rabbit rescue/Shelter | 0.0001 | 4.32 | 16.80 | 65.27 | |||

| Not RHDV2 affected/RHDV2 affected | < 0.0001 | 1.51 | 2.13 | 3.02 | |||

| Not COVID-19 affected/COVID-19 affected | 0.0498 | 1.001 | 2.40 | 5.76 | |||

| (c) Owner surrenders only (excl. adoption returns) (n = 59) | |||||||

| Rabbit rescue/Shelter | 0.046 | 1.03 | 4.92 | 23.45 | |||

| Not RHDV2 affected/RHDV2 affected | 0.0046 | 1.18 | 1.69 | 2.43 | |||

| Not COVID-19 affected/COVID-19 affected | 0.0012 | 1.85 | 4.62 | 11.56 | |||

| Abbreviations: Adj. P value, Tukey-adjusted P value; Adj. LL, Tukey-adjusted 95% lower confidence limit; LL, unadjusted 95% lower confidence limit; UL, unadjusted 95% upper confidence limit; Adj. UL, Tukey-adjusted 95% upper confidence limit; n, sample size. a‘e.g. born on site, stray, abandoned, owner surrender, adoption return, confiscated, transferred from another organization’. |

|||||||

The final mixed model for rabbit intakes of all types (n = 65 organizations) included only the main fixed effects of organization type, RHDV2, and COVID-19. Rabbit rescues took in 4.95 times more rabbits per year (95% CI, 1.71–14.33; P = 0.0038) as shelters, averaged across RHDV2 and COVID-19 status groups. Organizations not impacted by RHDV2 took in 1.61 times more rabbits per year (95% CI, 1.31–1.98; P < 0.0001) than those impacted, averaged over organization type and COVID-19 status. Organizations whose rabbit care was not affected by COVID-19 took in 2.73 times more rabbits per year (95% CI, 1.35–5.54; P = 0.0055) than those affected, averaged over organization type and RHDV2 status.

For stray/abandoned rabbit intakes (n = 61 organizations), the final model contained year, organization type, RHDV2, and COVID-19. One significant Tukey-adjusted year-to-year comparison (see Table 5) showed that in 2020, 0.60 times as many rabbits per year (95% CI, 0.42–0.85; P = 0.0008) were taken in compared with 2021, averaged over organization type, and RHDV2 and COVID-19 statuses. Rabbit rescues took in 16.80 times more rabbits per year (95% CI, 4.32–65.27; P = 0.0001) than shelters averaged over year, and RHDV2 and COVID-19 statuses. Organizations not impacted by RHDV2 took in 2.13 times more rabbits per year (95% CI, 1.51–3.02; P < 0.0001) than those impacted, averaged over year, organization type, and COVID-19 status. Organizations whose rabbit care was not affected by COVID-19 took in 2.40 times more rabbits per year (95% CI, 1.001–5.76; P = 0.0498) than affected organizations, averaged over year, RHDV2 status, and organization type.

For surrendered rabbit intakes (n = 59 organizations), the final model included organization type, RHDV2, and COVID-19, with results interpreted similarly to the all-intakes model.

Qualitative analysis of comments

Participants (n = 55) responding to the open-ended question about item 1, the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on rabbit care, described three themes. Responses to the additional open-ended questions, items 2 (n = 79) and 3 (n = 67), included similar and new themes. For more details about all items, see Supplementary material – detailed qualitative results.

Item 1: Comments describing how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the organization’s ability to care for domestic rabbits (n = 55)

The three themes identified from responses to item 1 were reduced rabbit intake and adoptions, simultaneous factors impacting organizations, and resource problems.

Reduced intakes occurred as organizations declined surrender requests and expanded their waiting lists. Some stopped taking in rabbits altogether or accepted only strays or emergencies to adjust to reduced capacity: ‘During 2020, [we] had to default to emergency intake only due to uncertainty around being able to stay open, and modifications made to staffing levels to ensure [we] could continue operations’ [P32]. One organization reduced rabbit capacity to accommodate cats. Others described lost opportunities for adoption appointments and events on-site and/or at partner stores, which further impacted intake. One participant explained: ‘With pet stores being closed it was difficult to place them once we get [sic] them into our care. For that reason we had to reduce our intakes as much as possible’ [P23]. While most reported challenges, two organizations noted more adoptions during this period; however, for one, this led to a new challenge: ‘We saw a huge surge in adoptions in 2020, but the returns and new surrenders are at an all-time high starting around August 2021’ [P48].

Many organizations described multiple concurrent operational impacts, including combinations of reduced donations, staff, volunteers, adoption events and appointments, fundraising and foster opportunities, and access to supplies, including food. Many noted the co-occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic and RHDV2 as problematic: RHDV2 added burdens, requiring further adaptations (e.g. arranging quarantines, vaccination expenses, and managing extended length of stay (LOS)). For two organizations, remaining open was a challenge, as illustrated in this quote:

… On top of everything we have dealt with from Covid, to RHVD [sic] ban on operations through Corporates [sic] politics, our spay and neuter Vet has since retired so now we are still hunting for a Vet partner to do our spays/neuters at a low cost for our nonprofit. […] These things have been determinantal [sic] to our operations and we have even had to consider closing our doors because we just don’t have the support we need. [P5]

In contrast, one organization described several positive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (increased vegetable donations, increased adoptions, and a successful online fundraiser); they also noted that RHDV2 did not affect them until mid-2022.

Resource issues were frequently mentioned, with human resource problems most common, e.g. ‘No volunteers or additional staff for [the] first 2 years of [the] pandemic’ [P6]. Some organizations with foster programs reported challenges to foster capacity and assessing new fosters: ‘It was much harder to vet fosters without visiting their home. A walk-through on Zoom was okay but not the same’ [P16]. Other resource concerns included reduced supply access, inadequate rabbit housing, and less time to exercise rabbits because of overworked/absent personnel. Financial strain due to fundraising difficulties was also reported, as exemplified by one participant: ‘Donations go down which effects [sic] us the most as that’s how we stay open’ [P38]. One organization dealing with RHDV2 also cited vaccine costs: ‘Yes, we quarantine any strays that we take in. All rabbits are vaccinated prior to adoption. This means that we lose money on every adoption made’ [P25].

Item 2: Comments describing differences seen in rabbits found stray or abandoned, or being relinquished in 2022, compared to before (n = 79)

Differences related to rabbit characteristics included age, health status, behavior, sterilization status, appearance, and sex; however, for age and health status (the most frequently reported) and sex, no clear patterns emerged. Although we asked if organizations noticed changes in the rabbits, many participants commented instead on the numbers they were seeing, breeders’ practices, surrendering owners, and growing concern over the lack of pet-friendly housing. Several noted increased numbers of abandoned rabbits, e.g. ‘More abandoned rabbits because all rescues are full’ [P14]. Others felt pressure to take in owner surrenders and transfers, e.g. ‘We are seeing an increase in demand for us to intake rabbits (from citizens and other rescues/shelters)’ [P27].

Item 3: Comments in response to the final survey question requesting any additional information about domestic rabbits and the organization’s role in caring for them (n = 67)

The primary themes were the capacity to care for rabbits, practices identified as contributing to success, and veterinary care. A minor theme was education.

The capacity to care for rabbits centered around the detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and RHDV2 on operations, long LOS, and difficulty finding good fosters and adopters as intake waiting lists grew. One organization described rabbit challenges thusly: ‘They are one of the hardest species for us to find room in a foster home for, take some of the longest time getting adopted out, and there are almost always several on our waiting list’ [P40]. Another expressed frustration as follows: ‘This rabbit crisis needs to stop … I feel its [sic] putting a huge strain on care for facilities and we are all running out of options’ [P22]. Some cared for many rabbits, e.g. ‘… 180 on a daily basis’ [P34]. Others described rising numbers of stray and abandoned rabbits and growing, unmanaged feral populations. Many described concerning numbers of surrender requests as shown in the following quote:

We don’t track the intakes by type, but in 2021 and 2022 we have taken Very Few owner surrenders – because of lack of capacity. We do track intake requests. In 2021 we had 353 requests to help 575 rabbits. 301 of these were rehomes, 262 were strays. In 2022 through mid-August we had 316 requests to help 649 rabbits. 392 of these were rehomes, 244 were strays. These numbers demonstrate the dramatic increase in the rabbit problem. … [P25]

In contrast, one organization [P18] described declining numbers, which they attributed to pre-adoption sterilizations and microchipping and improved housing in adopters’ homes. These efforts are part of another theme: practices identified as contributing to success. Other such practices identified by participants include pre-adoption bonding and litter training, partnerships with local pet stores and rabbit groups for temporary housing and adoptions, providing detailed information packages to prospective/current owners, using local/social media, a no-questions-asked return policy, and operating solely via foster homes. In contrast to these partnerships, one organization described challenges with the local animal services agency and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, both of which took in few or no rabbits.

Many organizations described needing basic and advanced veterinary care for intake exams, treatment of injuries and other issues, RHDV2 vaccinations, and sterilizations. Several described cost-related access problems: [P4] described it as ‘a huge barrier’ for ‘mandatory spay/neuter’. The need for low-cost sterilizations for owned rabbits was also described.

Organizations described the need for educating prospective and current owners (particularly about RHDV2), breeders, and pet stores on companion rabbit care and welfare.

Discussion

In our models, the only significant yearly change was a decrease in stray/abandoned rabbit intakes, with 0.6 times fewer intakes in 2020 compared with 2021. Qualitative findings showed some organizations halted stray/abandoned intakes, while others limited intakes to strays, emergencies, and/or injured animals due to mandates and capacity issues, but the exact timing of these changes is unclear. Another study found that total rabbit intakes at 36 shelters in BC decreased each year from 2017 to 2021, with a relatively small decrease between 2020 and 2021.12 Our 2019 data show that, even then, 22% of participants were already not taking in stray and abandoned rabbits. By 2021, most participants were turning away owners (86.2%) and managing waiting lists (78.6%), suggesting many had reached or neared capacity. Also by 2021, 82.0% of organizations had foster programs, some of which may have been new and responses to the evolving situation, while others were part of standard care. In our partial 2022 data (January–November), 88.5% of organizations declined surrender requests and 80.0% maintained waiting lists, pointing to further strain. Whether turning owners away contributes to rabbits being released outdoors has not been studied nor has the effectiveness of shelters in helping owners keep or rehome rabbits themselves. Since rabbits can experience fear and reduced welfare from multiple moves8 or being released outside, research is needed to identify factors linked to successful adoptions and retention. A method for reducing pet relinquishment while also improving animal welfare at the community level has been proposed.33 Through input sought from community stakeholders (e.g. shelter, pet owners, veterinarians, pet stores, and influencers), community-level needs and interventions can be determined.33 This approach could be explored for rabbits in communities where shelters and rabbit rescues are overburdened.

COVID-19 impact

Two-thirds of participants reported that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their ability to care for domestic rabbits. Qualitative results suggest simultaneous, multifactorial impacts, including RHDV2. For rabbits already in care, welfare was sometimes compromised by less exercise time due to overworked/absent personnel. Modeling suggests that organizations whose rabbit care was not impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic were able to take in twice as many rabbits. Other researchers have reported mixed COVID-19 pandemic impacts on cat and dog intakes, potentially due to differences in location and study periods.34 Longer lockdowns in Canada may partially explain the higher proportion of affected organizations in our Canadian subsample.

Rabbit intake can be associated with organizational capacity,10 and many participants indicated their organizations had reached that limit. We did not ask about intake rules or formal management models, such as the Capacity for Care (C4C) model, which has been used successfully with cats in Canada35 and the USA,36 and may also have been applied to rabbits by some surveyed organizations. C4C’s evolution into the Four Rights model – Right Care, Place, Time, and Outcome – emphasizes tailored animal care.37 Whether or not participants formally used these models, some may have employed their strategies under pressure. Four organizations were based in California, home to the California Animal Shelter COVID Action Response (CASCAR) group. CASCAR notes from 2021 reflect that the pandemic helped the group to appreciate the benefits of scheduled appointments, fewer visitors, and improved staff control.38 Research is needed to evaluate rabbit-specific management models.

Some organizations reported decreased veterinary care access, which aligns with research on reduced access for cats and dogs in Canada and the USA early in the COVID-19 pandemic,39,40 and reduced access continuing into mid-2022 for Canadian cat and dog owners.41 Initiatives that improve access to rabbit-knowledgeable, affordable veterinary care for shelters, rabbit rescues, and rabbit owners could help protect rabbit welfare through vaccinations and by mitigating unwanted breeding that can have downstream impacts on shelters, owners, and feral rabbit populations. For example, the House Rabbit Society (Richmond, CA) has a veterinary training initiative for veterinary professionals, which offers in-person experience with sterilizations, anesthesia, and recovery.42 Also, rabbit-specific training could be improved for veterinary students by veterinary schools partnering with shelters and rescues requiring low-cost and accessible services.

RHDV2 impact

RHDV2 decreased intakes at 60% of study organizations by 2022. Modeling of 2017–2021 data suggests that unaffected organizations took in at least 1.6 times more rabbits than those affected by RHDV2. No interactions between COVID-19 and RHDV2 were observed in our models, possibly due to only a single yes/no COVID-19 measurement. Not all participating provinces or states reported RHDV2 impacts, which is consistent with case reports in domestic and feral rabbits and wild rabbits/lagomorphs in the USA.43 When participants commented about RHDV2, they indicated disruptions to rabbit care. Concerns about domestic rabbits prompted responses, including education, vaccination, and quarantine – all of which have been associated with decreasing RHDV2 spread by mid-2023.44 As of March 2025, the boundaries of a ‘stable-endemic area’ of RHDV2 encompass counties in the western half of the USA, with greater case detection in wild rabbits than domestic rabbits, but with no cases reported in some counties.43 Sporadic domestic rabbit cases have been reported in counties in the eastern USA between 2020 and 2024, but there were no cases reported for wild rabbits. RHDV2 cases have also been reported in the province of Quebec in 2023 and 2024.43 Since RHDV2 continues to evolve and numerous highly pathogenic and highly virulent recombinant strains have been reported elsewhere (e.g. Europe,45–47 Australia,48 and China,49,50), vigilance, emergency planning, appropriate vaccination of domestic rabbits, and careful coordination at the community level are needed. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians has recently published publicly available guidelines for humane rabbit housing in animal shelters, which include recommendations for the prevention and mitigation of Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease.51

Organization type

Modeling suggests that rabbit rescues may play a key role in safeguarding rabbit welfare, as their intakes were at least five times higher than those of shelters across all intake categories. However, the CIs were larger than for COVID-19 and RHDV2 variables. Participants described the long LOS for rabbits compared to other animals, which is consistent with the literature.4,11,12 Bricks and mortar organizations are vulnerable to large-scale infectious disease outbreaks51 and may have limited intakes accordingly. Study participants also described problems with sourcing appropriate fosters and adopters. Intake rules have been hypothesized to affect reported relinquishment reasons at rabbit rescues, e.g. prioritizing younger rabbits,52 but these criteria were not queried in our study. Intake criteria may differ between rabbit rescues and large shelters, which may have more strict rules about capacities. House Rabbit Society rescues often pull rabbits at risk of euthanasia from shelters.53 It is possible that the rabbit rescues in our study may have larger foster programs or are wholly foster-based.

Rabbit relocation between organizations was common and has previously been documented.3,4,12 Several participants described stressful conditions – full shelters and rescues, requests to take in more rabbits, lack of cooperation with local agencies on stray pickups, and lost outreach opportunities due to COVID-19. Regardless of organization type, coordination and local buy-in appear crucial to support rabbit welfare and personnel, especially during emergencies, e.g. the introduction of a new RHDV2 variant.

Participants reported that the COVID-19 pandemic affected their ability to retain and properly screen fosters. Retaining dog fosters was also problematic in the USA, where increased fostering (with new and preexisting fosters) was seen at shelters early in the pandemic, although it did not last beyond May 2020.54 In addition to participant reports of losing rabbit fosters when fosters returned to work after lockdowns in our study, many – especially new – rabbit fosters may have been unprepared for taking care of rabbits. Lack of preparedness is consistent with research about unwanted rabbits, where some relinquishing owners appear unprepared for the time and attention rabbits need.4,8,10,12 Creating or enhancing rabbit foster programs (where fosters feel well supported) may be an opportunity to increase organizational resilience; however, these programs are resource-intensive and require rabbit-knowledgeable personnel, and sufficient financial and physical resources. In another survey study, involving dog fosters, results suggested high resource inputs as the dog fosters believed that higher foster retention may be achieved with sufficient communication between fosters and shelters; more financial and medical support, animal training, mentorship, and enrichment advice; and a responsive, foster community network.55 Future research that assesses rabbit foster programs and their impacts would be beneficial.

Shelters in our study reported that rabbits had the longest LOS. In previous studies in the USA, UK, and Canada, median and longest LOS ranged from 24 to 88 days and 288–718 days, respectively.4,11,12 Since rabbits are prey animals,56 intake diversion for rabbits directly to foster homes so that they do not enter shelters with rabbit predators (e.g. cats and dogs) could improve the rabbits’ welfare: this approach has been recommended by the Association of Shelter Veterinarians.51 The Community Cat Superhighway model,57 which adopts out unowned kittens without sheltering them, may offer a useful approach. Again, further research is needed to explore the benefits of foster programs for rabbits and to validate methods to expedite adoptions (e.g. foster-to-adopt programs) to reduce shelter pressure.

Healthy euthanasia was rare in our sample, while fostering was widely used. In BC (Canada) shelters, the 2017–2021 euthanasia rate was 9.8%, excluding owner-requested euthanasia (ORE).12 Euthanasia and fostering were not discussed in an earlier Canadian study,3 but a US study using 2005–2010 data reported that some shelters euthanized rabbits (range: 5.9–22.7% excluding ORE) and rarely used foster care (range: 0–16.7% of rabbits/shelter).4 In the US study, the shelter that used fostering the most showed a significant negative correlation between fostering and euthanasia.4 Our participants did not mention ORE, while 234 ORE cases were recorded in the US study.4 Further research is needed on the relationship between fostering and healthy euthanasia, and the reasons for ORE within and across countries.

Study limitations

We do not know how many organizations care for unwanted rabbits in Canada and the USA, but our sample is small, and the majority were Canadian. Other authors have noted the challenge of collecting data from rabbit rescues11 even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, non-representativeness of the sample, potential recall bias (from relying on memory, not recorded data), and self-selection bias (from keenness to share challenging experiences motivating participation) may impact the generalizability of the modeling. Also, the study collected a one-time measure of COVID-19 impact instead of annual data, which limited model refinement and potentially reduced the accuracy of estimates, so modeling results should be interpreted with caution. The qualitative results, however, are not meant to be generalized, instead reflect the nuanced experiences of those who did participate, and help deepen the understanding of the quantitative results. Overall, real-time data collection could support more accurate estimates and inferences. If shelters and rabbit rescues contributed rabbit data to centralized repositories (e.g. Shelter Animals Count), interested personnel and researchers would be better positioned to assess local, regional, national, and international metrics.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that many participating organizations caring for domestic rabbits in Canada and the USA faced complex, simultaneous challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic and RHDV2 emergencies, which significantly reduced rabbit intakes for shelters (vs. rabbit rescues) and for stray and abandoned rabbits in 2020 compared to 2021. Other ongoing challenges into 2022 included limited staff, fosters, and other volunteers, and funding for veterinary care and other expenses. Many organizations in our sample appeared to have reached capacity limits over the study period. They could no longer take in rabbits despite demand, as they cared for this unique, resource-intensive species that needs adequate housing and often costly veterinary care, long stays, transfers between organizations, and foster and waiting list programs. Our findings highlight opportunities for improvement and resilience building through emergency planning; more fosters; validated strategies to move rabbits more quickly through shelters to adoption (or increased reliance on foster-based rescues); expanded community partnerships; affordable veterinary care for shelters, rescues, and the public; and the evaluation of rabbit management models, including foster programs.

Statement of ethics

The University of Guelph’s Research Ethics Board (REB) approved the study as compliant with federal guidelines for research involving human participants (REB #22-05-013). Informed consent materials – including permission to use quotes, the study’s purpose, details on requested data, and data storage – along with recruitment content (advertisements, emails, and social media posts) were approved by the REB.

Author contributions

Carol E. Tinga: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, (personal) funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, software, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. Jason B. Coe: validation, writing – review & editing. Lee Niel: conceptualization, (personal) funding acquisition, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the animal welfare personnel across Canada and the USA who completed the survey and permitted us to share their quotes. We also appreciate the individuals and organizations that helped disseminate recruitment materials. We would like to thank OVC biostatistician William Sears for support with modeling and for providing helpful feedback on the presentation of results text and tables. Grammarly was used in the preparation of the thesis chapter. Grammarly and ChatGPT were used for spelling and grammar checks before manuscript submission. ChatGPT was also used by the first author to suggest changes to reduce the last 8% of the word count and to improve sentence clarity in the first submitted manuscript. All AI-assisted content was personally verified by the first author. Numerous suggestions by two reviewers have greatly improved this paper.

Author notes

Material from this manuscript was previously presented in abstract and poster form at the 32nd International Society for Anthrozoology Conference, University of Edinburgh, June 17, 2023: Animal shelter and rabbit rescue experiences with domestic rabbits in Canada and the USA (2017–2022). A more detailed version of this research project is available in C. Tinga’s thesis.58

References

| 1. | Crowell-Davis S. Rabbit Behavior. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2021;24(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2020.09.002 |

| 2. | McMahon SA, Wigham E. ‘All Ears’: A Questionnaire of 1516 Owner Perceptions of the Mental Abilities of Pet Rabbits, Subsequent Resource Provision, and the Effect on Welfare. Animals. 2020;10(10):1730. doi: 10.3390/ani10101730 |

| 3. | Ledger RA. The Relinquishment of Rabbits to Rescue Shelters in Canada [Abstract Only]. J Vet Behav. 2010;5(1):36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2009.10.016 |

| 4. | Cook AJ, McCobb E. Quantifying the Shelter Rabbit Population: An Analysis of Massachusetts and Rhode Island Animal Shelters. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2012;15(4):297–312. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2012.709084 |

| 5. | Davis SE, DeMello M. Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural and Cultural History of a Misunderstood Creature. Lantern Books, 2003. |

| 6. | Díaz-Berciano C, Gallego-Agundez M. Abandonment and Rehoming of Rabbits and Rodents in Madrid (Spain): A Retrospective Study (2008–2021). J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2022;27(4):712–722. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2022.2162342 |

| 7. | Ulfsdotter L. Rehoming of Pet Rabbits in Sweden. Student Report #478. Swedish University of Agriculture, 2013. Accessed Dec 17, 2025. https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/5998/1/Ulfsdotter_L_130829.pdf |

| 8. | Ulfsdotter L, Lundberg A, Andersson M. Rehoming of Pet Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Sweden: An Investigation of National Advertisement. Anim Welf. 2016;25(3):303–308. doi: 10.7120/09627286.25.3.303 |

| 9. | Falconer J. Humans of Animal Advocacy: Michelle Kelly | The Founder and CEO of the Los Angeles Rabbit Foundation Has Transformed Rabbit Care at LA Shelters. HumanePro – Humane Society of the United States. Accessed Nov 8, 2023. https://humanepro.org/magazine/articles/humans-animal-advocacy-michelle-kelly |

| 10. | Neville V, Hinde K, Line E, Todd R, Saunders RA. Rabbit Relinquishment through Online Classified Advertisements in the United Kingdom: When, Why, and How Many? J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2018;22(2):105–115. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2018.1438287 |

| 11. | Ellis CF, McCormick W, Tinarwo A. Analysis of Factors Relating to Companion Rabbits Relinquished to Two United Kingdom Rehoming Centers. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2017;20(3):230–239. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2017.1303381 |

| 12. | U ASY, Hou CY, Protopopova A. Rabbit Intakes and Predictors of Their Length of Stay in Animal Shelters in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One. 2024;19(4):e0300633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0300633 |

| 13. | World Health Organization. Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020. 2020. Accessed Nov 14, 2023. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 |

| 14. | Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Canadian COVID-19 Intervention Timeline. 2022. Accessed Jul 10, 2024. https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-covid-19-intervention-timeline |

| 15. | Dasgupta S, Kassem AM, Sunshine G, et al. Differences in Rapid Increases in County-Level COVID-19 Incidence by Implementation of Statewide Closures and Mask Mandates – United States, June 1–September 30, 2020. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;57:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.02.006 |

| 16. | Combden S, Forward A, Sarkar A. COVID-19 Pandemic Responses of Canada and United States in First 6 Months: A Comparative Analysis. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2022;37:50–65. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3323 |

| 17. | National Animal Care & Control Association. NACA Statement on Animal Control Functions During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Accessed Jul 10, 2024. https://www.nacanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/1.General-Statement-on-Animal-Control-Functions-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.r.pdf |

| 18. | Humane Canada. Community-Supported Animal Sheltering Policy Platform. 2023. Accessed Oct 29, 2025. https://humane-canada.ca/en/your-humane-canada/news-and-reports/reports/community-supported-animal-sheltering-policy-platform |

| 19. | Anon. Guelph Humane Society Has Too Many Rabbits, and Not Enough Adopters. CBC Kitchener-Waterloo. September 8, 2021. Accessed Jan 4, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kitchener-waterloo/guelph-humane-society-surge-in-rabbits-1.6166509 |

| 20. | Anon. From a Bunny Surge to a Need for Food: Animal Groups Reflect on Another Pandemic Year for Pets. CBC News Windsor. January 2, 2022. Accessed Jan 3, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/windsor-essex-pandemic-year-pets-1.6300809 |

| 21. | Anon. Quebec Animal Shelters Overwhelmed by Rabbits as Advocates Call for Stricter Regulations. CBC News Montreal. January 3, 2022. Accessed Jan 4, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/pandemic-rabbits-abandoned-montreal-quebec-shelters-1.6303026?fbclid=IwAR1IAD5tJMrXK_yQHmb4XYC8a4yQakrQ6No_cQK7G89uNl8KxPhY6GeWxwo |

| 22. | Campbell T. Bay Area Shelters Make Plea to Pet Owners as Facilities Overflow with Abandoned Animals. ABC7 San Francisco. October 27, 2022. Accessed Apr 27, 2024. https://abc7news.com/bay-area-animal-shelters-pet-adoption-abandoned-animals-pandemic-pets/12387327/ |

| 23. | Larson A. Bay Area Shelters Overloaded with Rabbits. KRON4. August 18, 2022. Accessed Apr 27, 2024. https://www.kron4.com/news/bay-area/bay-area-shelters-overloaded-with-rabbits/ |

| 24. | Le Gall-Reculé G, Zwingelstein F, Boucher S, et al. Detection of a New Variant of Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus in France. Vet Rec. 2011;168(5):137–138. doi: 10.1136/vr.d697 |

| 25. | Le Gall-Reculé G, Lavazza A, Marchandeau S, et al. Emergence of a New Lagovirus Related to Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus. Vet Res. 2013;44:81. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-44-81 |

| 26. | Rouco C, Aguayo-Adán JA, Santoro S, Abrantes J, Delibes-Mateos M. Worldwide Rapid Spread of the Novel Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus (GI.2/RHDV2/b). Transbound Emerg Dis. 2019;66(4):1762–1764. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13189 |

| 27. | Asin J, Calvete C, Uzal FA, et al. Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2, 2010–2023: A Review of Global Detections and Affected Species. J Vet Diagnostic Investig. 2024;36(5):617–637. doi: 10.1177/10406387241260281 |

| 28. | Hawai`i Department of Agriculture. Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Confirmed on Maui – Quarantine Order Issued. 2022. Accessed Jul 4, 2022. https://hdoa.hawaii.gov/blog/main/nr-rabbitdisease/ |

| 29. | Government of Canada. Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease (RHD) Fact Sheet. Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2023. Accessed Nov 21, 2023. https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/diseases/immediately-notifiable/rhd/fact-sheet |

| 30. | Braun V, Clarke V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa |

| 31. | Braun V, Clarke V. Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches. Couns Psychother Res. 2021;21:37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360 |

| 32. | Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 4th ed. (Seaman J, ed.). SAGE, 2018. |

| 33. | Powdrill-Wells N, Bennett C, Cooke F, Rogers S, White J. A Novel Approach to Engaging Communities Through the Use of Human Behaviour Change Models to Improve Companion Animal Welfare and Reduce Relinquishment. Animals. 2025;15(7):1036. doi: 10.3390/ani15071036 |

| 34. | Carroll GA, Reeve C, Torjussen A. Companion Animal Adoption and Relinquishment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Experiences of Animal Rescue Staff and Volunteers. Anim Welf. 2024;33:e12. doi: 10.1017/awf.2024.15 |

| 35. | Karsten CL, Wagner DC, Kass PH, Hurley KF. An Observational Study of the Relationship between Capacity for Care as an Animal Shelter Management Model and Cat Health, Adoption and Death in Three Animal Shelters. Vet J. 2017;227:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.08.003 |

| 36. | UC Davis – Koret Shelter Medicine Program. October 9, 2025 Update. Accessed Oct 28, 2025. https://www.sheltermedicine.com/programs/maddies-million-pet-challenge/ |

| 37. | Koret Shelter Medicine Program. Four Rights. n.d. Accessed Aug 5, 2025. https://www.shelterlearniverse.com/visitor_class_catalog/category/126596 |

| 38. | CASCAR: California Animal Shelter COVID Action Response | Koret Shelter Medicine Program. June 1, 2021. Accessed Nov 7, 2023. https://www.sheltermedicine.com/services/cascar/ |

| 39. | Guerios SD, Porcher TR, Clemmer G, Denagamage T, Levy JK. COVID-19 Associated Reduction in Elective Spay-Neuter Surgeries for Dogs and Cats. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:912893. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.912893 |

| 40. | Muzzatti SL, Grieve KL. Covid Cats and Pandemic Puppies: The Altered Realm of Veterinary Care for Companion Animals during a Global Pandemic. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2022;25(2):153–166. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2022.2038168 |

| 41. | Jacobson LS, Janke KJ, Probyn-Smith K, Stiefelmeyer K. Barriers and Lack of Access to Veterinary Care in Canada 2022. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2024;3(1):1–12. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v3.72 |

| 42. | House Rabbit Society. Veterinary Training Initiative. n.d. Accessed Oct 15, 2025. https://houserabbit.org/veterinaryinitiative |

| 43. | United States Department of Agriculture – Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Map Application. 2020–24 Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2. 2025. Accessed Jul 29, 2025. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/rabbit-hemorrhagic-disease-map |

| 44. | Lederhouse C. Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease’s Spread Appears to be Slowing. AVMA News. 2023. Accessed Aug 25, 2023. https://www.avma.org/news/rabbit-hemorrhagic-diseases-spread-appears-be-slowing |

| 45. | Capucci L, Cavadini P, Schiavitto M, Lombardi G, Lavazza A. Increased Pathogenicity in Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus Type 2 (RHDV2). Vet Rec. 2017;180(17):426. doi: 10.1136/vr.104132 |

| 46. | Le Minor O, Boucher S, Joudou L, et al. Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease: Experimental Study of a Recent Highly Pathogenic GI.2/RHDV2/b Strain and Evaluation of Vaccine Efficacy. World Rabbit Sci. 2019;27(3):143–156. doi: 10.4995/wrs.2019.11082 |

| 47. | Mohamed F, Gidlewski T, Berninger ML, et al. Comparative Susceptibility of Eastern Cottontails and New Zealand White Rabbits to Classical Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus (RHDV) and RHDV2. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69(4):e968–e978. doi: 10.1111/tbed.14381 |

| 48. | Hall RN, King T, O’Connor T, et al. Age and Infectious Dose Significantly Affect Disease Progression after RHDV2 Infection in Naïve Domestic Rabbits. Viruses. 2021;13:1184. doi: 10.3390/v13061184 |

| 49. | Hu B, Fan Z, Qiu R, et al. Novel Recombinant Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2 (RHDV2) Is Circulating in China within 12 Months after Original RHDV2 Arrival. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2023;2023:4787785. doi: 10.1155/2023/4787785 |

| 50. | Hu B, Dong W, Song Y, Fan Z, Cavadini P, Wang F. Detection of a New Recombinant Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus 2 in China and Development of Virus-Like Particle-Based Vaccine. Viruses. 2025;17(5):710. doi: 10.3390/v17050710 |

| 51. | Schumacher E, Berliner E, Hicks S, et al. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ Guidelines for Humane Rabbit Housing in Animal Shelters. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2025;4(S2):149. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v4.149 |

| 52. | Ellis C, McCormick W, Tinarwo A. Rabbit Relinquishment to Two UK Rescue Centres and Beyond. Poster presented at: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare Conference. June 23, 2016, York, UK. ResearchGate; 2016:1. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.1.2212.3124 |

| 53. | House Rabbit Society – San Francisco Bay Area Center (HRS – SFBAC). Adopting a Rabbit. n.d. Accessed Mar 27, 2025. https://houserabbit.org/how-to-adopt |

| 54. | Gunter LM, Gilchrist RJ, Blade EM, et al. Emergency Fostering of Dogs from Animal Shelters During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Shelter Practices, Foster Caregiver Engagement, and Dog Outcomes. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:862590. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.862590 |

| 55. | Reese L, Jacobs J, Pratt G, Vanslembrouck H, Werner G. Dog Foster Volunteer Retention. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2025;28(3):419–434. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2024.2355523 |

| 56. | McBride EA. Small Prey Species’ Behaviour and Welfare: Implications for Veterinary Professionals. J Small Anim Pract. 2017;58(8):423–436. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12681 |

| 57. | University of Florida Shelter Medicine Program. The Community Cat Superhighway – The Right Outcome for Every Cat. 2024. Accessed Jun 11, 2024. https://sheltermedicine.vetmed.ufl.edu/shelter-services/the-right-outcome/the-community-cat-superhighway/ |

| 58. | Tinga CE. Bunny Bonds and Shelter Stories: Understanding Human-Rabbit Relationships and Recent Trends in Managing Unwanted Companion Rabbits. PhD Thesis, University of Guelph, 2025. https://hdl.handle.net/10214/28788 |