ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Post-Adoption Behavior and Adopter Satisfaction of Shelter Kittens Identified as Undersocialized Prior to Adoption

Jacklyn J Ellis1*, Kyrsten J Janke1, Matthew De Luca1 and Vicky Halls2

1Toronto Humane Society, Toronto, ON, Canada; 2International Cat Care, Tisbury, United Kingdom

Abstract

Introduction: Undersocialized kittens pose an ethical challenge for shelters. Although undersocialized kittens (especially those under 12 weeks) are thought to adapt better than undersocialized adults, data on their long-term welfare and adopter satisfaction are limited. This study examines behavioral outcomes and adopter experiences for Undersocial and Control kittens, above and below 12 weeks of age.

Methods: At least 1 year after placement, a survey was administered to adopters of kittens who were >1 and <7 months old at intake. Multinomial logistic regressions and Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to identify significant differences between groups (Undersocial<12 weeks, Undersocial>12 weeks, Control<12 weeks, and Control>12 weeks) in reported behavioral traits (8 traits, 1–5 Likert scale), responses to situational social interactions (approach and petting, from owner and stranger), and adopter experience (satisfaction 1–5 Likert scale, categorical classification of feelings toward the cats, and categorical classification of what type of environment would make the cat happiest).

Results: Of the 724 adopters surveyed, overall differences between groups were minimal. Fearfulness was the only trait significantly associated with group: Control<12 weeks kittens were 71% less likely and Control>12 weeks kittens were 65% less likely to be rated as fearful compared to Undersocial<12 weeks kittens. Responses to stranger approach and petting also differed: Undersocial<12 weeks kittens were more likely to react negatively than Control<12 weeks kittens. Owner-directed behaviors (approach and petting) showed no meaningful differences between groups. Adopter satisfaction was high across all groups (95–98%), most adopters described loving their kittens (96–99%) and thought their kitten would be happiest in a traditional home environment (89–93%).

Conclusion: Both age groups of Undersocial kittens were more fearful and wary of strangers, but all groups formed strong bonds with adopters. There was no notable difference between Undersocial kitten age groups, suggesting adoption is a viable, welfare-positive option when intake sources and resources allow.

Keywords: feline; socialization period; human-animal bond; adoptability; welfare; feral; behavior; petting; approach; traits; shelter

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2026, 5: 150 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v5.150

Copyright: © 2026 J. J. Ellis et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 19 January 2025; Revised: 31 December 2025; Accepted: 1 January 2026 Published: 12 February 2026

Competing interests and funding: The Canada Summer Jobs program provided funding to employ the research assistant during data collection. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Correspondence: *Jacklyn J. Ellis Toronto Humane Society, Toronto, ON, Canada. Email: jellis@torontohumanesociety.com

Reviewers: Margaret Slater, Sheila Segurson

Supplementary material: Supplementary material for this article can be accessed here.

Pathway planning for undersocialized kittens presents an ethical challenge for animal shelters. Kittens not socialized to humans during the sensitive period of 2–8 weeks of age may struggle to adapt to life in a traditional home environment.1,2 During this critical window, positive human interactions can establish strong social bonds; however, after this period, socialization efforts require increasing time and effort, and may have insufficient results.3,4a Previous research5 has indicated that adult cats found to be ‘Unlikely’ or ‘Extremely unlikely’ to be socialized by the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals’ (ASPCA) Feline Spectrum Assessment (FSA) experience poorer welfare outcomes in home environments compared to their socialized counterparts. Many organizations caution against pursuing socialization efforts for undersocial kittens who arrive at a shelter older than 12 weeks of age.a,b Many kittens arrive in shelters outside this optimal timeframe, raising concerns about the ability to socialize undersocial kittens enough to properly prepare them for experiencing positive long-term welfare in a home and suitability for adoption.

Understanding the welfare outcomes and adopter experiences of undersocialized kittens compared to socialized ones is crucial to refining shelter protocols and improving placement success. However, the FSA cannot be applied to cats under 6 monthsc and currently no tool has been developed to quantify the likelihood of a kitten’s socialness. Therefore, shelters must rely on the experience of veterinarians, Registered Veterinary Technician (RVTs), and experienced animal behavior staff to make this determination.

This study aims to assess post-adoption follow-up data to evaluate differences in behavior and adopter experience between kittens identified as Undersocial and a group of Control kittens (who were not identified as Undersocial and are therefore presumably socialized) across age at intake by month, ≥1 and <7 months of age. We hypothesize that kittens identified as Undersocial will have poorer post-adoption outcomes than Control kittens, and that these poor outcomes will be more profound in the >12-week age group as compared to the <12-week age group. By examining multiple measures of kitten behavior and adopter experience, this research will help to inform best practices for shelters managing Undersocial kittens to enhance placement success.

Methods

This retrospective cohort with follow-up study surveyed adopters of Undersocial and Control kittens on their first adoption from Toronto Humane Society. Kittens were identified as Undersocial by veterinary or training staff. This determination was based on informal assessment of fear-related behaviors (e.g. hissing, fleeing, ear flattening) and the absence of relaxed behaviors (e.g. playing, grooming, approaching) in the presence of humans. When available, information provided at intake (such as response to human approach/petting and containment method) was considered. This approach is not a validated method for identifying Undersocial kittens, but is standard practice in shelters as no validated alternative currently exists2; the FSA is not validated for kittens. Kittens not identified as Undersocial (and therefore, presumed socialized) served as the Control group.

Included kittens had their first intake between May 17, 2018 and May 18, 2022, were ≥1 month and <7 months of age at intake, had an adoption outcome, had been in the adoptive home for ≥1 year, and had an adopter email address on file. While in shelter, all kittens identified as Undersocial received daily behavioral modification sessions consisting of desensitization and counter-conditioning to human approach/touch and adopters were provided resources to continue the socialization process at home (link to a video used as a part of the behavior modification plan training: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OSHPQVd4fMc). All kittens were housed in portalized cages or out-of-cage spaces and were provided hiding boxes, elevated perching opportunities, and toys.

Adopters were surveyed regarding the prevalence and degree of behavioral traits, response to situational social-directed behavior (petting and approach) by either their adopter or a stranger, and owner experience. The survey used was based on the companion study survey by Ellis et al.5 with slight adaptations to improve clarity and applicability to kittens and to disentangle out-of-box urination (OOBU) and out-of-box defecation (OOBD) (Supplementary Material). Adopters were asked to rate the presence of eight behavioral traits (fearful, playful, active, aggressive, affectionate, vocal, OOBU and OOBD) on a scale from 1 (not exhibited) to 5 (very frequent). They were subsequently asked to report the cat’s situational responses to both owner and stranger approach (1 = Come Toward, 2 = Stay in Place, 3 = Run Away, 4 = Already Hiding/Attempt to Scratch or Bite, or 0 = I don’t know) and petting (1 = Enjoy, 2 = Tolerate, 3 = Avoid, or 0 = I don’t know). Adopters were sent a study notification email6,7 to ensure informed consent to confidential data collection and use, offered a prize draw,8–12 and contacted by email and telephone up to four times or until survey completion.

Prior to analysis of the survey results, Undersocial and Control kitten population characteristics (age at intake, fostering, length-of-stay (LOS) in shelter, LOS in adoptive home prior to being surveyed, and intake type) were compared using Fisher’s exact tests (α = 0.05). As these variables may influence behavior within the adoptive home, they were included in subsequent analysis. Undersocial and social kittens were divided by age, <12 weeks and >12 weeks, in accordance with a common cut-off after which organizations caution against pursuing socialization efforts.

To assess differences in adopter-rated behavioral traits between groups, a multinomial logistic regression was performed with group (>12 weeks Undersocial, <12 weeks Undersocial, >12 weeks Control, <12 weeks Control) as the outcome variable and treated as categorical data. The eight behavioral traits were included as predictor variables and treated as ordinal data, while demographic factors were also included as predictor variables and treated as numerical (LOS in Shelter & LOS in Adoptive Home) or as categorical (Foster Stay and Intake Type). The final model was determined using forward selection, with predictors added and removed stepwise to assess contribution to model fit based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and McFadden’s pseudo-R2. Multicollinearity was evaluated through generalized VIF and linearity in the logit was evaluated via Box-Tidwell test and splines introduced when necessary.

To assess differences in adopter reported behaviors exhibited in hypothetical situations between groups, a multinomial logistic regression was performed with group as the outcome variable and treated as categorical data. The situational response behaviors were included as predictor variables and treated as ordinal data, while demographic factors were also included as predictor variables and treated as above. Model building and assessment of model assumptions were performed as above.

Adopter satisfaction (1–5 Likert scale), feelings toward their cat (‘I love my cat’, ‘I am fond of my cat’, ‘I have neutral or negative feelings for my cat’, or ‘I don’t know’), and what type of living environment they thought would make their cat the happiest (‘Living in a standard home environment with an owner’, ‘Living strictly outdoors with no owner, but food is provided regularly and they can choose to interact with people if they want to’, or ‘I don’t know’) were assessed across groups. Fisher’s exact tests assessed overall association and cell-level significance was evaluated using standardized residuals and Bonferroni-adjusted p-values.

Results

Within the study period, 2,033 kittens (≥1 month, <7 months) were admitted to the shelter. Before sending the survey, 572 kittens were excluded. Kittens were excluded because they did not have an adoption outcome (n = 113), missing adopter contact information (n = 77), or they had been in their adoptive home for <1 year at the time of survey (n = 382). Ultimately, the adopters of 1,461 kittens were sent surveys. The total response rate was 50% (737/1,461), with a response rate of 54% (136/252) for Undersocial kittens and 50% (601/1,211) for Control kittens. Thirteen more were excluded because surveys revealed the adopter retained the kitten <1 year prior to being surveyed (6 = kittens died, 4 = rehomed on their own, 1 = surrendered the kitten elsewhere, 2 = escaped and did not return). The remaining 724 kittens were included in the study.

Of the 134 Undersocial kittens (66 = female, 68 = male; 64<12 weeks old, 70>12 weeks old) and 590 Control (276 = female, 314 = male; 399<12 weeks old, 191>12 weeks old), 2.2 and 1.9% were returned following adoption, respectively. As the four groups differed significantly in intake type (p = 0.002), LOS in care (p < 0.001), LOS in adoptive home (p < 0.001), and likelihood of a foster stay (p < 0.001), these variables (Table 1) were included in subsequent regression analyses to account for baseline differences between groups. It was noted that both Undersocial groups were significantly more likely to have an ‘Owner Surrender’ intake type. While surprising, it bears mentioning that Toronto Humane Society under certain circumstances admits colony cats as custodial surrender instead of stray, which is an intake sub-type of ‘Owner Surrender’.

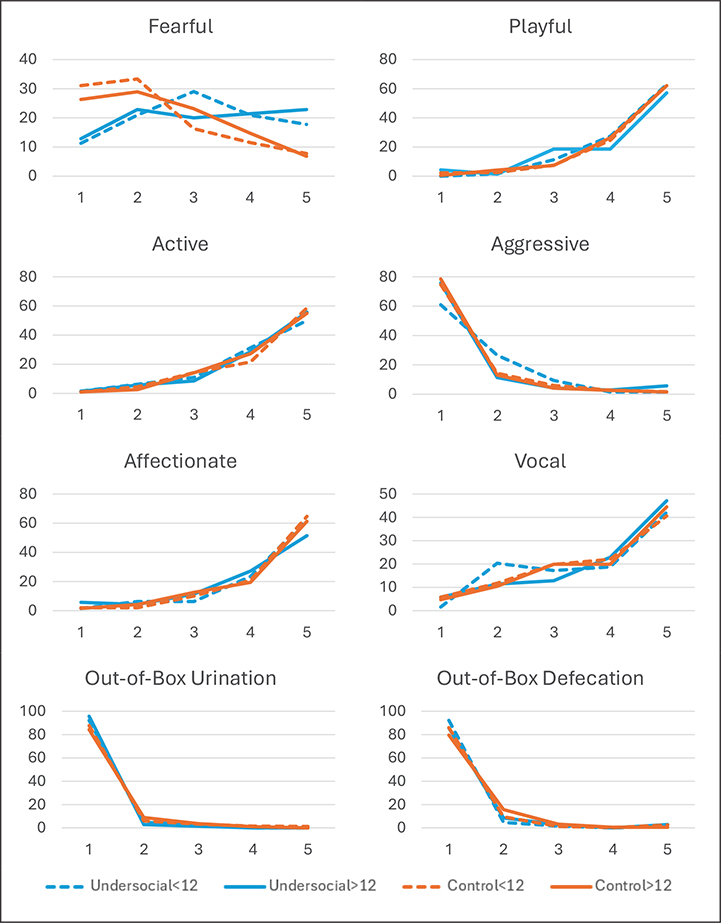

Fearful was the only trait found to differ significantly between groups by a multinomial logistic regression (McFadden’s pseudo-R2 = 0.26). Compared to Undersocial<12 weeks, Control<12 weeks kittens were 71% less likely to be rated as fearful, and Control>12 weeks kittens were 65% less likely. There was no significant difference in fearfulness between Undersocial>12 weeks and Undersocial<12 weeks kittens (Table 2). Aggression was not significantly different between groups but strengthened the fit of the model so was retained. All other traits were removed from the model and exhibited extreme skewness (overrepresentation of responses in categories at one end of the scale or the other) that was consistent across all groups. Figure 1 provides a visual description of the data spread of each trait.

| Predictor | Group | Coeff (log) | Standard error | Odds ratio | 95% CI (upper and lower) | P-value | |

| Fearful | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 1.20 | 0.46–3.12 | 0.704 | ||

| Control <12 | -1.24 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.13–0.62 | 0.002** | ||

| Control >12 | -1.05 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.15–0.82 | 0.015** | ||

| Aggressive | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | 0.53 | 0.90 | 1.70 | 0.29–9.95 | 0.559 | ||

| Control <12 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 1.23 | 0.23–6.57 | 0.805 | ||

| Control >12 | 0.246 | 0.87 | 1.28 | 0.23–7.14 | 0.779 | ||

| Foster stay (Yes) | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | -1.28 | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0.07–1.04 | 0.058 | ||

| Control <12 | 1.94 | 0.41 | 6.95 | 3.10–15.60 | <0.001** | ||

| Control >12 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 1.29 | 0.54–3.09 | 0.563 | ||

| Intake type | Transfer | Reference value | |||||

| Owner surrender | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 1.03 | 0.43–2.49 | 0.947 | ||

| Control <12 | -1.08 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.17–0.70 | 0.003** | ||

| Control >12 | -1.30 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 0.13–0.58 | <0.001** | ||

| Stray | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | -0.04 | 0.57 | 0.96 | 0.31–2.94 | 0.938 | ||

| Control <12 | -0.38 | 0.45 | 0.69 | 0.28–1.66 | 0.404 | ||

| Control >12 | -0.64 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.21–1.34 | 0.180 | ||

| LOS in care (days) | Modeled using splines (df = 3). Coefficients not shown. | ||||||

| LOS in adoptive home (years) | Modeled using splines (df = 3). Coefficients not shown. | ||||||

| Playful | Removed from model | ||||||

| Active | Removed from model | ||||||

| Vocal/Talkative | Removed from model | ||||||

| Out-of-box urination | Removed from model | ||||||

| Affectionate | Removed from model | ||||||

| Out-of-box defecation | Removed from model | ||||||

| ‘I don’t know’ responses (n = 5) were not included in analyses: Undersocial<12 = 2, Control<12 = 2, Control>12 = 1). ɑ = 0.05; **Significant; McFadden’s pseudo-R2 = 0.26. LOS: length of stay. | |||||||

Fig. 1. Percent of adopter rating for eight traits (1–5 Likert scale: 1 = not exhibited, 5 = very frequent) across four groups of kittens: Undersocial<12 weeks, Undersocial>12 weeks, Control<12 weeks, and Control>12 weeks. ‘I don’t know’ responses are not represented graphically: Fearful = 3 (Undersocial<12 = 2, Social>12 = 1), Playful = 2 (Social<12 = 2), Active = 0, Aggressive = 2 (Social<12 = 2), Affectionate = 4 (Social<12 = 2, Social>12 = 2), Vocal = 1 (Social>12 = 1), Out-of-Box Urination = 5 (Social<12 = 1, Social>12 = 4), Out-of-Box Defecation = 3 (Social<12 = 2, Social>12 = 1).

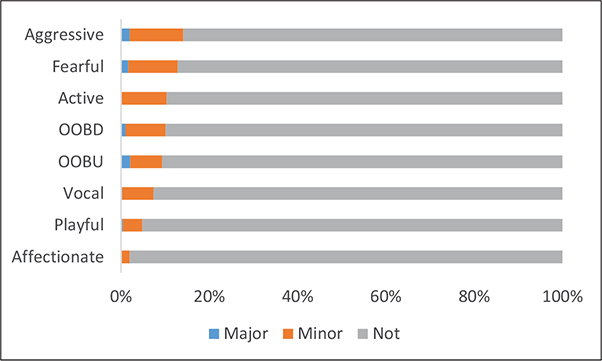

Of the total study population, >85% of adopters reported each trait as neither majorly nor minorly problematic (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Percent of traits reported as majorly, minorly, or non-problematic by adopters, inclusive of all 4 groups of kittens. ‘I don’t know’ responses were not included in percent calculations, nor represented graphically.

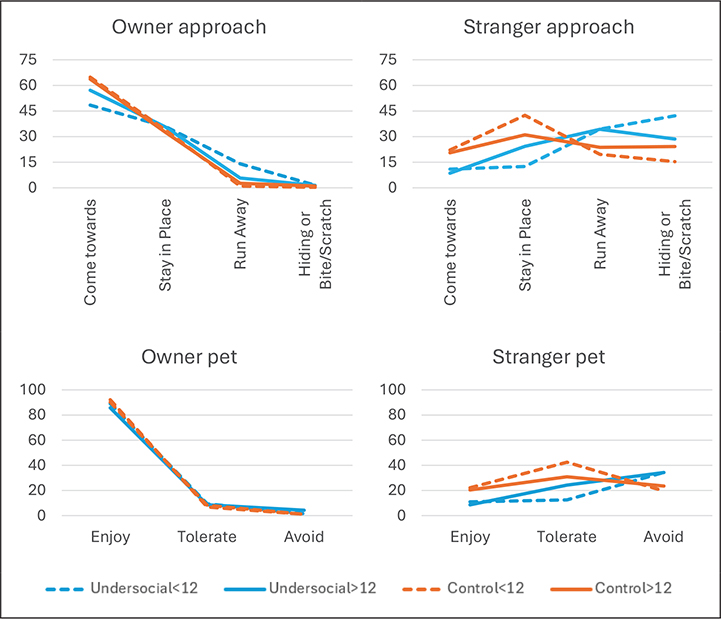

Response to both approach and petting attempts from a stranger differed significantly between groups in a multinomial logistic regression (McFadden’s pseudo-R2 = 0.29). Compared to Undersocial<12 weeks, Control<12 weeks kittens were 60% less likely to respond negatively to stranger approach and 50% less likely to respond negatively to stranger petting. Control>12 weeks kittens did not differ significantly from Undersocial<12 weeks for these behaviors. Owner petting showed an unexpected pattern: Control<12 weeks kittens were over 12 times more likely to respond negatively than Undersocial<12 weeks kittens (OR = 12.32, 95% CI 1.55–97.89, p = 0.018), likely due to the overwhelming predominance of ‘Enjoy’ being reported. This variable was retained for model completeness but should be interpreted with caution (Fig. 3). All other behaviors were removed from the model due to lack of significance and overrepresentation of responses in categories at one end of the scale or the other.

Fig. 3. Percent of adopter reported situational behaviors (categorical) in response to approach or petting attempts from either the owner or a stranger across four groups of kittens: Undersocial<12 weeks, Undersocial>12 weeks, Control<12 weeks, and Control>12 weeks. ‘I don’t know’ responses are not represented graphically: Owner approach = 2 (Control<12 = 1, Control>12 = 1), Stranger approach = 8 (Undersocial>12 = 3, Control<12 = 3, Control>12 = 2), Owner pet = 3 (Undersocial>12 = 1, Control<12 = 2) Stranger pet = 21 (Undersocial<12 = 2, Undersocial>12 = 1, Control<12 = 12, Control>12 = 6).

While the majority of adopters were satisfied (95–98% of all groups rated 4/5 or 5/5), the overall Fisher’s exact test indicated a statistically significant association between group and adopter satisfaction (p = 0.019). Cell-level analysis revealed that adopters of Undersocial<12 kittens reported satisfaction 4/5 (standardized residual = 3.18, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.029) more frequently and satisfaction level 5/5 (standardized residual = -3.46, Bonferroni-adjusted p = 0.011) less frequently than expected under the null hypothesis of independence.

The majority of adopters reported loving their kitten (96–99% of all groups) and thought their kitten would be happiest in a traditional home environment (89–93% of all groups). The Fisher’s exact test did not indicate a statistically significant association between groups and either adopter feelings toward their cat (p = 0.712) or where adopters thought their kitten would be happiest (p = 0.099).

Discussion

Overall, there were few differences between the groups in any of the eight traits, the four situational behaviors, or the adopter experience questions. The most notable differences emerged in the trait of fearfulness and in the patterns of stranger initiated situational behaviors. Statistical testing and visual inspection of distributions revealed that differences were more meaningful between socialization categories than between age categories. Interestingly, Undersocial kittens were not reported to be less affectionate than Control kittens, nor was there a meaningful difference in response to approach or petting from the owner between socialization groups. These results suggest that while having a poor socialization history may result in fearfulness, particularly toward novelty, these kittens are still capable of forming meaningful bonds with primary caretakers. Contrary to expectations, being younger or older than 12 weeks at intake was not related to adopter ratings of any of the behavioral traits. This finding may be a product of insufficient statistical power, and increased sample sizes may allow for detection of subtle differences between undersocial kittens intaken at less than or greater than 12 weeks of age.

Fearfulness was the only behavioral trait that was significantly different between groups. Table 2 shows that both Control<12 and >12 (but not Undersocial>12) were significantly different than Undersocial<12, and visual inspection of the Fearful graph in Fig. 1 illustrates that patterns in fearful ratings seem more similar within socialization categories than within age categories. Similarly, the stranger-specific situational response questions revealed Undersocial kittens more likely to respond with behaviors easily interpreted as fearful. Table 3 shows Control<12 is significantly different than Undersocial<12, and visual inspection of both the approach and petting graphs in Fig. 3 illustrates that patterns in situation response to social initiation by strangers seem more similar within socialization categories than within age categories. In short, Undersocial kittens behaved in a more fearful manner regardless of age group, but this response was more dramatic to strangers than it was to their owners. In fact, the only significant difference between groups in terms of situational response to social initiation by owners (Owner pet for group Control<12) is likely a product the overwhelming predominance of ‘Enjoy’ being reported (which is conspicuous through visual inspection of Fig. 3) and therefore likely not reflective of a biologically relevant difference. These findings align with expectations, confirming that the lack of early socialization results in persistent wariness toward novel humans – despite targeted socialization efforts in shelter or foster. They are also consistent with the findings of Ellis et al.5 who asked the same questions for Undersocial adult cats. However, it is worth noting that there was a difference in magnitude between the responses for Undersocial kittens and cats. The average percentage of adopters of adult cats assessed by the FSA reported to be likely to ‘come towards’ an approaching owner was 35% (kittens: Undersocial<12 = 48%, Undersocial>12 = 57%) and the average percentage for ‘run away’ was 23% (kittens: Undersocial<12 = 14%, Undersocial>12 = 6%). The average percentage of adult cats assessed by the FSA reported to be likely to ‘avoid’ a stranger petting them was 70% (kittens: Undersocial<12&>12 = 34%). While trends of where significant differences lay and in what direction are consistent between studies, a smaller percentage of Undersocial kittens were reported to be exhibiting these undesirable responses than were the adult cats assessed by the FSA.

| Predictor | Group | Coeff | Standard error | Odds ratio | 95% CI (upper and lower) | P | |

| Owner approach | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | -0.85 | 1.40 | 0.43 | 0.03–6.63 | 0.543 | ||

| Control <12 | -2.42 | 1.43 | 0.09 | 0.01–1.47 | 0.090 | ||

| Control >12 | -0.33 | 1.08 | 0.72 | 0.09–5.90 | 0.756 | ||

| Stranger approach | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 1.03 | 0.37–3.12 | 0.963 | ||

| Control <12 | -0.92 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.17–0.95 | 0.039* | ||

| Control >12 | -0.68 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.21–1.26 | 0.143 | ||

| Owner pet | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | 1.43 | 1.04 | 4.18 | 0.55–31.84 | 0.167 | ||

| Control <12 | 2.51 | 1.06 | 12.32 | 1.55–97.89 | 0.018* | ||

| Control >12 | 0.73 | 1.10 | 2.07 | 0.24–17.89 | 0.510 | ||

| Stranger pet | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | -0.049 | 0.41 | 0.95 | 0.42–2.14 | 0.907 | ||

| Control <12 | -0.70 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.25–0.99 | 0.046* | ||

| Control >12 | -0.25 | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.38–1.57 | 0.483 | ||

| Intake type | Transfer | Reference value | |||||

| Owner surrender | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 1.21 | 0.50–2.89 | 0.672 | ||

| Control <12 | -1.05 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.17–0.72 | 0.004* | ||

| Control >12 | -1.21 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.14–0.63 | 0.001* | ||

| Stray | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 1.65 | 0.53–5.08 | 0.385 | ||

| Control <12 | -0.06 | 0.46 | 0.94 | 0.38–2.32 | 0.902 | ||

| Control >12 | -0.32 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.29–1.82 | 0.491 | ||

| LOS in care (days) | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.96–1.00 | 0.118 | ||

| Control <12 | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | <0.001* | ||

| Control >12 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | <0.001* | ||

| Foster stay (Yes) | Undersocial <12 | Reference value | |||||

| Undersocial >12 | -1.67 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.05–0.68 | 0.010* | ||

| Control <12 | 2.14 | 0.39 | 8.47 | 3.99–18.06 | <0.001* | ||

| Control >12 | -0.20 | 0.41 | 0.82 | 0.37–1.85 | 0.637 | ||

| LOS in adoptive home (years) | Modeled using splines (df = 3). Coefficients not shown. | ||||||

| ‘I don’t know’ responses (n = 30) were not included in analyses: Undersocial<12 = 2, Undersocial>12 = 5, Control<12 = 16, Control>12 = 7). α = 0.05; *Significant; McFadden’s pseudo-R2 = 0.29. LOS: length of stay. | |||||||

This study of Undersocial kittens produced three key findings that did not align with Ellis et al.’s5 Undersocial adult cat study. Firstly, Ellis et al.5 found that Undersocial adult cats were rated as less affectionate than Controls, while this study found no difference in affection ratings between groups. Correspondingly, the second difference was that Ellis et al.5 found that Undersocial adult cats were less likely to have a positive response and more likely to have a negative response to approach or petting by their owners, while this study found no difference in response to approach or petting by the owner between groups (with the exception of the difference in response to owner petting between Control<12 and Undersocial<12, which visual inspection of the data distribution reveals no meaningful difference and is likely a product of the overwhelming predominance of ‘Enjoy’ being reported). While Undersocial kittens are more fearful in general than Controls, these two findings indicate that they are capable of forming meaningful bonds with their primary caregiver – something that was less apparent with the Undersocial adult cats in Ellis et al.’s5 study. This is further supported by the final difference Ellis et al.5 found that owners of the Control cats were more likely to report that their cats would be happiest in a traditional home environment and less likely to report that their cat would be happiest in an outdoor environment than Undersocial adult cats, while this study found no difference in where the owner thought their pet would be happiest between groups, which could further imply evidence of a meaningful bond. All of this suggests that while kittens identified as Undersocial in shelter are reported as more fearful in their subsequent adoptive home than Controls – which can be indicative of high stress/poor welfare – the lack of meaningful difference between groups in affection and enjoyment of petting by owner (and high proportion reported in both groups) suggest evidence that Undersocial kittens have positive interactions with known humans, which can be indicative of low stress/good welfare.13–15 The evidence of a meaningful bond with their primary caregiver suggests that they would have good welfare when interacting with the normal inhabitants of their home and that periods of prolonged fear would be restricted to times when they encounter unfamiliar people (visitors to the house, vet trips, etc.) or animals, sudden unexpected noises, or new objects. As this is not what was found by Ellis et al.,5 it can be concluded that Undersocial felines adopted as kittens are more likely to have good welfare in a traditional home environment than those adopted as adult cats.

Perhaps the most surprising finding was the absence of a notable difference in post-adoption behavior between Undersocial kittens that came in (and began formal socialization) before 12 weeks of age, and those that came in after that cut-off. This is despite the fact that conventional wisdom and previous research have shown that in both cats1 and dogs16 the closer to the sensitive phase of the socialization window socialization efforts begin the greater impact socialization efforts will have, and thus a kitten will be able to better integrate into a home environment. There are several possible explanations for this. Firstly, it is likely that the most unsocialized kittens (especially at later ages) were not suggested for intake/adoption, and instead underwent Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) (thus biasing our sample population). This could be interpreted as a selection bias17 when looking at the population as a whole, but if this resulted from a successful education campaign asking people not to request intake for kittens over a certain age unless they are showing signs of liking people and to opt for TNR instead, it may be representative of the population actually coming in for intake – undersocial rather than unsocial kittens. A second possibility is that when the medical or training teams designated the kittens as Undersocial, what they were really recognizing was fear associated with a shy temperament. Ellis et al.5 had the benefit of using the FSA (a validated tool developed to determine the difference between undersocialized and fearful but socialized cats, as the behaviors they exhibit can be very similar) to determine if a cat was socialized. There is no such tool that can be used to assess socialization in kittens. Ultimately, it may be impossible to differentiate between these two possibilities: a shy cat would be very fearful in a new environment but warm up after getting comfortable with someone, while an Undersocial kitten would be fearful until socialization efforts achieved success and they warm up with someone and this response may not generalize to others. Both of these descriptions line up with the behaviors of the kittens described as Undersocial in this manuscript. And as handling (and thus, socialization) can also contribute to temperament,18,19 ultimately perhaps the difference is academic. But, as methods similar to those described in this study are likely being used in most shelters evaluating pathway outcomes for kittens of questionable socialization status, these results may still have relevant real-world applications. A final possibility is that the behavior modification program employed for these kittens was successful. While general recommendations advise shelters against socialization attempts for kittens over a certain age, this may be because these efforts are known to require a great deal more time and resourcesd – beyond what most shelters are equipped to provide, especially when an adequate alternative live outcome is available. It may be that our organization simply dedicated more resources than typical to these efforts. The authors do not place a value judgement on one outcome being better than the other – whether an organization decides to attribute a large amount of resources to socialize a small number of kittens to adapt to life in a typical home or opts to TNR these kittens and use these same resources to help a larger number of cases is up to the mandate of each organization, and both outcomes are acceptable.

This study was subject to several limitations and results should be interpreted with these in mind. The designation of kittens as Undersocial in this study was not validated and may be prone to subjective bias or observations may have reflected something else such as temperament instead of socialization history. Adopters willing to take on kittens identified as Undersocial might be more patient, experienced, or supportive than average pet adopters, resulting in a self-selection bias20 at adoption, improving outcomes. A participation bias20 may have also played a role in the results: adopters with better experiences may have been more likely to respond. Reporting bias20 may have led adopters to justify the adoption as a success and social desirability bias21 may have caused underreporting of issues such as fear or aggression. This study also does not quantify the degree of Undersocial behavior exhibited that lead to the designation, or the degree of behavior modification progress made in shelter/foster before adoption, although either of these factors would likely have had an influence on results. Although great effort was made to control experiences in care before adoption (e.g. foster placement, LOS), some were still significant in the final models (Tables 2 and 3) and therefore may potentially have played a role in the significant differences seen between socialization groups. Finally, perhaps the biggest limitation of this study – at least when it comes to comparing it to Ellis et al.5 – is that this study surveyed adopters at least 1 year after adoption, while the previous study surveyed adopters at least 1 month after adoption. Ellis et al.5 selected the 1 month time period as previous research indicated cats from a hoarded environment had substantial increases in social behavior in a quarter of this amount of time.22 However, it is likely that reductions in undesirable behaviors and increases in desirable behaviors continue past this time frame, and that the much more favorable results produced in this study on kittens could have been in part because of the longer time in the adopter’s home. It is also possible that concerning behaviors toward strangers increase with age simply because increased time provides more opportunities to express/observe these behaviors. There was also feedback from a few adopters that they had a difficult time being certain what behavior their kitten was exhibiting 1 year after adoption, and may instead be reporting behavior from more recent time periods, resulting in a recency effect.23 There could also be value in comparing responses of adopters of kittens that have completed the ‘junior’ life stage category (>2 years old)24 and those that have not, to investigate the impact of developmental maturity, on outcome variables.

Conclusion

This study offers promising insights into the long-term outcomes of adopting Undersocial kittens. While these kittens exhibited increased fearfulness and hesitancy around strangers post-adoption, they were still capable of forming strong, affectionate bonds with their adopters and showed no increased risk of problematic behaviors such as aggression. The absence of a notable difference in post-adoption behavior between Undersocial kittens that came in before or after the 12 week cut-off suggests that adoption can be a viable and welfare-positive pathway in some situations, particularly in communities that only request intake for kittens over a certain age if they are showing signs of liking people and organizations that prioritize scarce resources to further socializing these kittens. These findings highlight that despite a questionable history of human exposure in the sensitive phase of the socialization window, Undersocial kittens tend to have good welfare in adoptive homes, and adopter experience appears positive.

Authors’ contributions

Study conceptualization and funding acquisition was completed by JJE. Study refinement aided by VH. Data collection completed by MDL. Data curation and analysis completed by KJJ. Writing – original draft was completed by JJE and KJJ. Writing – review & editing was completed by all authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Canada Summer Jobs program for funding the research assistant during data collection, and the members of the International Cat Care’s International Unowned Cat Working Group for feedback on study design.

References

| 1. | Karsh EB, Turner DC. The Human-Cat Relationship. In: Turner DC, & Patrick B (Edtior). The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour. Cambridge University Press; 1988:159–177. |

| 2. | Slater MR, Miller KA, Weiss E, Makolinski KV, Weisbrot LAM. A Survey of the Methods Used in Shelter and Rescue Programs to Identify Feral and Frightened Pet Cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2010;12(8):592–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2010.02.001 |

| 3. | Gosling L, Stavisky J, Dean R. What Is a Feral Cat?: Variation in Definitions May Be Associated with Different Management Strategies. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15(9):759–764. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13481034 |

| 4. | Halls V, Ellis SLH, Bessant C. Outcomes for Kittens Born to Free-Roaming Unowned Cats. J Shelter Med Community Animal Health. 2023;2(S1):57. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.57 |

| 5. | Ellis JJ, Janke KJ, Furgala NM, Bridge T. Post-Adoption Behavior and Adopter Satisfaction of Cats Across Socialization Likelihoods. J Shelter Med Community Animal Health. 2025;4(1):116. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v4.116 |

| 6. | Yammarino FJ, Skinner SJ, Childers TL. Understanding Mail Survey Response Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Public Opin Q. 1991;55(4):613. doi: 10.1086/269284 |

| 7. | van Gelder MMHJ, Vlenterie R, IntHout J, Engelen LJLPG, Vrieling A, van de Belt TH. Most Response-Inducing Strategies Do Not Increase Participation in Observational Studies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;99:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.02.019 |

| 8. | Brennan M, Benson S, Kearns Z. The Effect of Introductions on Telephone Survey Participation Rates. Int J Market Res. 2005;47(1):65–74. doi: 10.1177/147078530504700104 |

| 9. | Bosnjak M, Tuten TL. Prepaid and Promised Incentives in Web Surveys: An Experiment. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2003;21(2):208–217. doi: 10.1177/0894439303021002006 |

| 10. | Gunn WJ, Rhodes IN. Physician Response Rates to a Telephone Survey: Effects of Monetary Incentive Level. Public Opin Q. 1981;45(1):109. doi: 10.1086/268638 |

| 11. | Tuten TL, Galesic M, Bosnjak M. Effects of Immediate Versus Delayed Notification of Prize Draw Results on Response Behavior in Web Surveys: An Experiment. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2004;22(3):377–384. doi: 10.1177/0894439304265640 |

| 12. | Laguilles JS, Williams EA, Saunders DB. Can Lottery Incentives Boost Web Survey Response Rates? Findings from Four Experiments. Res High Educ. 2011;52(5):537–553. doi: 10.1007/s11162-010-9203-2 |

| 13. | Amat M, Camps T, Manteca X. Stress in Owned Cats: Behavioural Changes and Welfare Implications. J Feline Med Surg. 2016;18(8):577–586. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15590867 |

| 14. | Casey RA, Bradshaw JWS. The Assessment of Welfare. In: Rochlitz I, ed. The Welfare of Cats. Animal Welfare. Springer Netherlands; 2007:23–46. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-3227-1_2 |

| 15. | Vojtkovská V, Voslářová E, Večerek V. Methods of Assessment of the Welfare of Shelter Cats: A Review. Animals. 2020;10(9):1527. doi: 10.3390/ani10091527 |

| 16. | Scott JP, Fuller JL. Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog. University of Chicago Press; 1964. |

| 17. | Krishna Mohan S, Mrsc M, Assistant F. Research Bias: A Review for Medical Students. J Clin Diagn Res. 2010;4:2320–2324. |

| 18. | Vitale Shreve KR, Udell MAR. What’s Inside Your Cat’s Head? A Review of Cat (Felis silvestris catus) Cognition Research Past, Present and Future. Anim Cogn. 2015;18(6):1195–1206. doi: 10.1007/s10071-015-0897-6 |

| 19. | Turner DC. A Review of Over Three Decades of Research on Cat-Human and Human-Cat Interactions and Relationships. Behav Processes. 2017;141:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2017.01.008 |

| 20. | Elston DM. Participation Bias, Self-Selection Bias, and Response Bias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021:S0190962221011294. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.025 |

| 21. | Alexander KC, Mackey JD, McAllister CP, Ellen III BP. What do you want to hear? A self-presentation view of social desirability bias. J. Bus. Res. 2025;189:115191. |

| 22. | Jacobson LS, Ellis JJ, Janke KJ, Giacinti JA, Robertson JV. Behavior and Adoptability of Hoarded Cats Admitted to an Animal Shelter. J Feline Med Surg. 2022;24(8):e232–e243. doi: 10.1177/1098612X221102122 |

| 23. | Turvey BE, Freeman JL. Jury Psychology. In: Ramachandran VS, ed. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2012:495–502. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-375000-6.00216-0 |

| 24. | Vogt AH, Rodan I, Brown M, et al. AAFP-AAHA: Feline Life Stage Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2010;12(1):43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.12.006 |

Footnotes

a https://www.kittenlady.org/socializing.

b https://www.ashevillehumane.org/wp-content/uploads/Feline-Socialization-Guide-Semi-Feral-and-Shy-Cats-and-Kittens.pdf.

c https://www.aspcapro.org/sites/default/files/ASPCA-FSA-manual-2016.pdf.

d https://phillypaws.org/wp-content/uploads/PAWS-Cat_Kitten-Socialization-Manual-2.pdf.