COMMUNITY CASE REPORT

Management of Free-Roaming Cat Populations In Slovakia: Attitudinal Perspectives of Residents Engaged With Unowned Cats – A Community Case Report

Noema Gajdoš-Kmecová1, Ann Enright2, Ivana Božíková3, Daniela Takáčová4 and Phil Assheton5

1Small Animal Clinic, University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy in Košice, Košice, Slovakia; 2Victoria, Australia; 3University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy in Košice, Košice, Slovakia; 4Department of Public Veterinary Medicine and Animal Welfare, University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy in Košice, Košice, Slovakia; 5Berlin, Germany

Abstract

Individuals working with unowned cats are key stakeholders in cat population management, yet comprehensive data on their involvement in Slovakia are lacking. This study aimed to characterize Slovaks engaged in unowned cat management through an online survey assessing demographics, attitudes toward management practices, challenges, and educational priorities. A total of 276 responses were analyzed, with most respondents being women (89%), 61% aged 31–50 years, and 52% involved in this work for less than 5 years. The majority (75%) were unaffiliated with any official organization.

Factor analysis revealed not only generalized views on domestic cat behavior but also conflicting attitudes toward population management. Cluster analysis using respondents’ factor scores identified a smaller subset (16%) who exhibited stronger opinions, suggesting greater emotional investment. Respondents expressed interest in further education, particularly Trap-Neuter-Return program planning and strategies for cats unsuitable for rehoming. Despite financial constraints being the main difficulty, education was largely accessible to most.

These findings highlight the potential benefits of training courses for volunteers, covering domestic cat biology, data collection, impact assessment, and financial planning. Such education could enhance decision-making and funding opportunities, ultimately supporting more effective urban cat management in Slovakia.

Keywords: felis catus; free-ranging cats; population management; volunteer caregivers; behavior change; education; training

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2025, 4: 133 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v4.133

Copyright: © 2025 Noema Gajdoš-Kmecová et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 11 April 2025; Revised: 6 May 2025; Accepted: 7 May 2025; Published: 10 July 2025

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Correspondence: Noema Gajdoš Kmecová Email: noemakmecova@gmail.com

Reviewers: Peter Wolf, Tatiana Sales

Supplementary material: Supplementary material for this article can be accessed here.

The world’s leading authorities regarding domestic cat population management distinguish between confined and roaming cats.1 Pet cats live exclusively indoors and are owned. Free-roaming cats may or may not have an owner. This group may include pet cats, street cats, abandoned pet cats, and ‘inbetweener’ cats.2,3 These distinct categories of cats are closely linked to the challenges many societies face in managing them. Authorities often struggle to respond adequately to the unique adaptability of cats, which can lead to a discordant coexistence between cats and humans. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach, including targeted research, community engagement, and evidence-driven policy interventions to align with One Welfare principles.1 Conducting a situational analysis prior to implementing interventions is vital to establish a baseline for evaluation and guide subsequent strategies.4,5

Background

Slovak households consistently show higher dog ownership (>900,000) than cat ownership (>500,000),6–8 potentially influencing public perceptions and policies on unowned cats. Unlike Austria, Italy, or France,9 Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) is neither defined nor legislated in Slovakia and rarely supported by municipalities. Decree No. 283/2020 Coll. outlines companion animal protection, stray animal management, and requirements for shelters and quarantine stations (holding facilities for trapped animals with unknown health status), and The Act on Veterinary Care of 2007 prohibits activities that may cause fear, pain, and suffering to animals. However, according to this act [§ 22 (17)], trapped animals must be held for 45 days before adoption, with no mention of release or TNR.

Of the 55 quarantine stations available for dogs and cats, only one is dedicated solely to cats, with some cities, including Košice, lacking facilities for cats altogether.10 In practice, cities often delegate cat management to shelters and civil associations (‘Občianske združenie’) that rely on volunteer foster carers.

Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) reportsa,b,c indicate cat population management in Slovakia depends heavily on community-driven initiatives with minimal municipal involvement, yet no official data exist on Slovaks working with unowned cats.

This study aims to characterize these individuals, assess their attitudes toward population management, and identify key challenges and educational priorities. Understanding their perspectives is vital for developing pilot programs and evidence-based urban cat management strategies. Ultimately, this research seeks to inform legislative and policy changes, improving free-roaming cat welfare in Slovakia.

Methods

Survey structure and distribution

The online survey was based on the ‘Working with unowned cats’ unpublished survey by International Cat Care, distributed in 2022. A Slovak version of the survey was developed, and minor modifications relevant for the aim of this study were made (e.g. addition of questions regarding decision-making on kittens and euthanasia, and adjustment of options for specific working areas).

The questionnaire consisted of four parts (A–D). Part A, ‘Opinions and attitudes’, focusing on practices of organizations helping unowned cats, TNR, euthanasia decision-making, and cats as a species, consisted of 23 statements with a 5-point Likert scale answer options (ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’). Two more control questions were included to identify potentially unreliable answers. Part B, ‘Challenges and Education’, focused on uncovering the most challenging aspects of working with cats, including overall interest and barriers in educational topics benefiting those working with cats, with multiple answer options (B1: 14 options plus ‘other’ – written answer, B2: 12 options plus ‘other’ – written answer, B3: 12 options including ‘do not wish to state’). Part C contained 5 demographic questions (Table 1). Finally, Part D targeted only those working or volunteering for official cat rescue organizations (shelter, civic association, and charity), including two questions regarding payment and employment (Table 1). Space for additional comments was provided at the end of the survey to collect data for future, qualitative analysis.

The online survey version was created using Google Forms and piloted with six testing respondents. Following minor adjustments (inconvenient survey display on mobile devices and missing ‘do not wish to state’ answer options), the survey was launched in October 2023, shared via social media (e.g. Facebook) using the snowball sampling method, and closed in December 2023. Participants were informed about the nature of the study, invited to confirm their voluntary participation, and that they are 18 years or older, with an option to provide an email address if interested in participating in further research. (See Supplementary material – translated questionnaire and link to the online survey). To increase the survey reach, a well-known NGO ‘Animal Ombudsman’ was contacted by email to assist with dissemination through social media and via their contact list.

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee for the approval of research involving animals in accordance with the legislative requirements applicable at the University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy (UVMP) in Košice (Ref: EKVP 2023-07).

Data analysis

Responses were removed if participants answered both Part A control questions incorrectly.

To characterize the population based on their level of agreement with the statements in Part A, responses for each Likert scale question were reduced using factor analysis (FA) with varimax rotation. Component selection was based on the examination of the ‘scree plot’ graph in combination with parallel analysis, taking into account the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue above 1) and the results of the goodness-of-fit test.

The FA model was used to compress the many responses per participant down to five factor scores. These scores were then used to identify different groups within the test population by fitting a Gaussian mixture model (a probabilistic method of clustering). The identified groups (clusters) were then back converted into average responses to the original survey questions and graphically characterized in a chart form. The analyses were performed in R, version 4.3.2, using the packages ‘factanal’ and ‘mclust’.

The challenges associated with working with unowned cats, as well as the interest in education and associated topics were characterized graphically using bar graphs with Clopper-Pearson exact proportion 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Demography

A total of 306 respondents completed the questionnaire, of which 10% (n = 30) of participants incorrectly answered two of the control questions and were subsequently removed from the study.

Similar responses from four participants to 21 of the 23 questions in Part A were considered valid due to their consistency and were retained in the dataset. For example, two of the four participants adjusted their answers for one of the two negatively worded questions. Additionally, all four answered the two control questions correctly, indicating that they were attentive while completing the questionnaire. As a result, the final sample consisted of 276 responses.

The majority of respondents were women (89%), with 61% aged between 31 and 50 years. Additionally, 52% had been involved in work with unowned cats for less than 5 years. Most respondents (75%) were not affiliated with any official organization (Table 1), and over half identified their work within the categories of caring for cats in colonies (55%) and foster care (53%, Table 1). Among the 62 respondents (22%) who were affiliated with an organization, only two (3%) were paid for their work. Furthermore, the majority of this group (73%; n = 45) were part of organizations with 10 or fewer members (Table 1).

Views and attitudes toward cat population management practices

After eliminating blank entries, 240 responses were incorporated into factor and cluster analyses. Five factors were selected to describe our population (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for methodology).

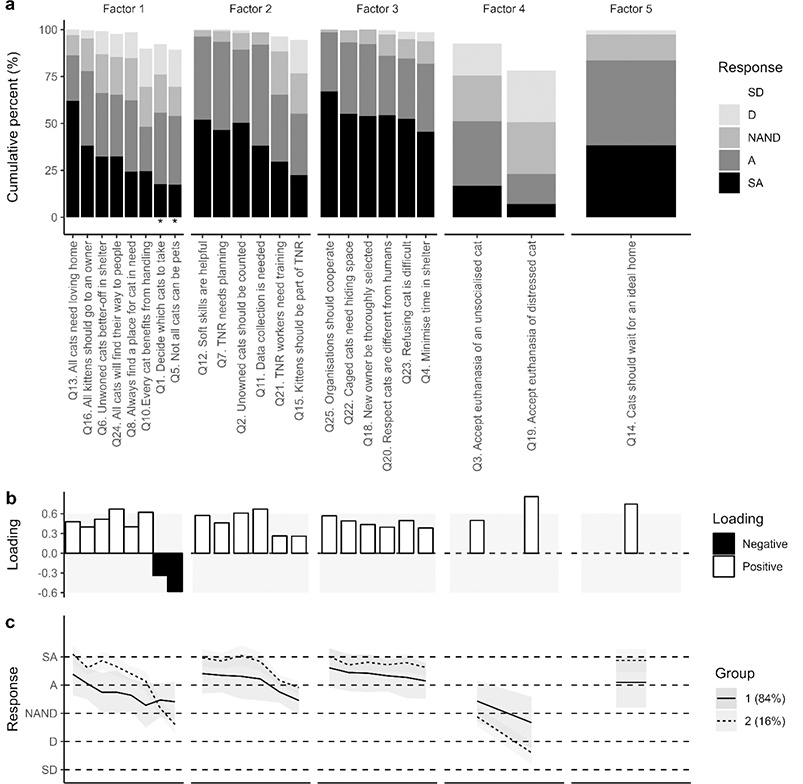

Factor 1 comprised of eight items related to perception of cats’ needs and homing process (Fig. 1a), two of which had negative loadings (‘Not all cats can be pets’, -0.58; ‘Organisations helping unowned cats should decide which cats to take in’, -0.34, Fig. 1b). Thus, respondents agreeing with six positively loaded statements (e.g. ‘All cats need a loving home’ or ‘All kittens should have an owner’) tended to disagree with the two negatively loaded ones (Fig. 1a and b).

Fig. 1. Results of factor analysis and cluster analysis (N = 240). (a) Responses to statements from Part A of the survey, ranked by (i) the factor within which they had the highest loading, (ii) the positive/negative value of the loading within that factor (negative loadings marked with asterisks), and (iii) the response´s mean cumulative percent (SD = Strongly Disagree, D = Disagree, NAND = Neither agree nor disagree, A = Agree, SA = Strongly agree). (b) The loading value of each item within the factor where it had the highest loading. The loadings for all claims within each factor can be found in Supplementary Table 1. (c) Summary of the two group characteristics identified by the clustering method using a Gaussian mixed model. The lines represent the mean values of each group. The shaded area represents one standard deviation below and above the mean.

Six positively loaded statements were grouped within factor 2, related to TNR practices such as data collection, planning, and associated training (Fig. 1a and b). Statements ‘Anyone who performs cat neutering (catch – neuter – return) should be trained to do so’ and ‘Kittens (less than 6 months of age) should be part of a spay/neuter program, i.e. trap-neuter-release to the original or new location’ had lower factor loadings (0.26) than other statements within this factor (≥0.46).

Likewise, factor 3 contained six positively loaded statements (ranging from 0.38 to 0.57) pertaining to shelter management practices (Fig. 1a and b). Factor 4 encompassed two statements about the acceptance of shelter euthanasia in distinct scenarios, both showing positive loadings. A larger proportion of respondents (51%) supported euthanizing cats that were very likely suffering, such as a non-socialized cat that was trapped and severely ill or had a guarded prognosis requiring long-term hospitalization. In contrast, only 23% supported euthanasia for a distressed cat recovering from an injury in an overcrowded shelter environment (Fig. 1a and b). The factor loading for the ‘non-socialized cat euthanasia’ (0.50) was lower, compared to the ‘distressed cat euthanasia’ (0.86).

Factor 5 contained one positively loaded statement: ‘Cats should remain in a shelter/foster care until an ideal home can be found for them’ (Fig. 1a and b).

For all data on factor loadings, see Supplementary Table 1.

Clustering by fitting various Gaussian mixture models (including correlated ones), the optimal (by Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC]) had two spherical Gaussians, suggesting the presence of two clusters. One of the clusters was larger and more widespread, comprising 84% of respondents, while the other smaller cluster comprised 16% of the test sample. It is evident that for factors 1, 2, 3, and 5, the smaller group was made up of respondents who were more extreme in their responses and chose the answer ‘Strongly agree’ for a larger proportion of the statements within these factors (Fig. 1c). The same respondents also responded more negatively to the negatively charged statements under factor 4. In Supplementary Fig. 2, the separation of two groups is explored; although group 2 sits right on the tail of group 1, due to its smaller size, it can be considered an extension added to group 1, with its respondents responding extremely strongly to most of the items.

Challenges and education preferences

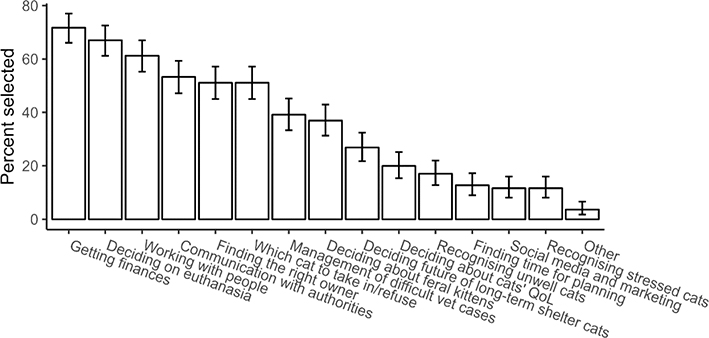

A majority of respondents reported obtaining finances (72%; CI 66–77), euthanasia decisions (67%; CI 61–73), and working with people (61%; CI 55–67) to be the most challenging aspects of working with unowned cats, with an additional three being communication with authorities (53%; CI 47–59), finding the right caregiver (51%; CI 45–57) and deciding which cat to take in or refuse (51%; CI 45–57, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Percentage of respondents (y-axis) selecting one or more options (x-axis) answering the item ‘Which of the following aspects of working with cats do you find most challenging’, N = 276. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Responses have been abbreviated to make the graph readable – the original versions are provided in the Supplementary material – Questionnaire.

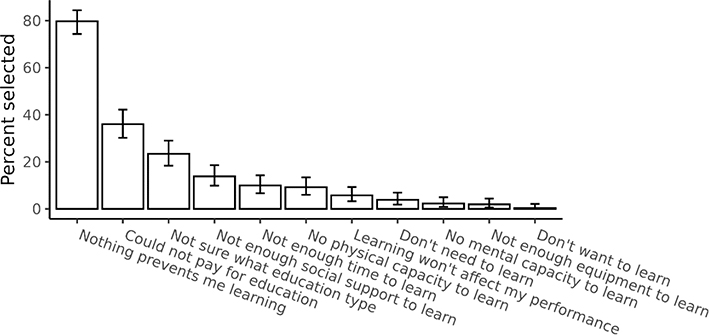

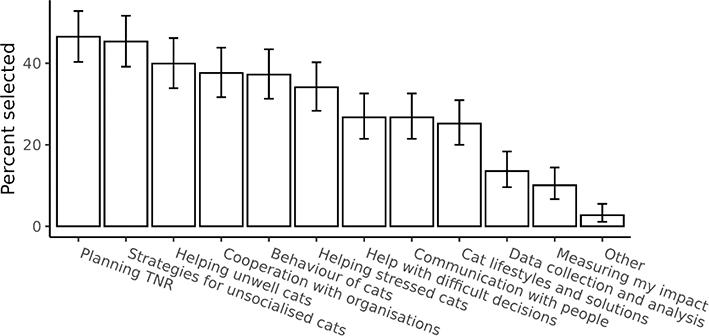

The majority of respondents (80%; CI 74–84) stated that nothing prevented them from learning; however, more than one third could not pay for education (36%; CI 30–42, Fig. 3). Two educational topics of highest interest were TNR program planning (47%; CI 40–53) and strategies for cats unsuitable for shelter or foster care (45%; CI 39–52, Fig. 4). Two topics of least interest were data collection and analysis (14%; CI 10–18) and measuring impact (10%; CI 7–14, Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Percentage of respondents (y-axis) selecting one or more options (x-axis) answering the item ‘Which of the following statements do you agree with (tick all that you agree with)’, N = 261. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Responses have been abbreviated to make the graph readable – the original versions are provided in the Supplementary material – Questionnaire. (‘Not wish to stay’ responses, n = 15, excluded from graphical presentation.)

Fig. 4. Percentage of respondents (y-axis) selecting one or more options (x-axis) answering the item ‘Please indicate your level of interest in a topic of education that would be helpful in your work with cats’, N = 258. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Responses have been abbreviated to make the graph readable – the original versions are provided in the Supplementary material – Questionnaire. (‘Not wish to stay’ responses, n = 18, excluded from graphical presentation.)

Discussion

This study aimed to profile the Slovak population working with unowned cats and provide a first screening study as a base for a situational analysis informing development of customized guidelines for cat population management in Slovakia. The demographic analysis highlighted that middle-aged women, often providing voluntary care for up to 5 years and not affiliated with rescue organizations, dominate this work. They exhibit a limited understanding of domestic cats’ biology and diverse lifestyles, generally agree on shelters’ roles, and report conflicting attitudes regarding shelter cat decisions (e.g. by agreeing that new owners should be thoroughly screened but also agreeing that the time a cat spends in the shelter should be minimized). While finances are the biggest challenge, our sampled population showed minimal interest in education on measuring impact and data collection. They did, however, recognize the importance of cat counting, TNR planning, and training. Their primary interest lies in learning about TNR and strategies for cats unsuitable for shelters.

Our findings indicate the majority of caregivers for unowned cats in Slovakia are women (89%), aligning with international survey results. For example, Neal and Wolf reported that 78.3% of caregivers in their U.S.-based study were female,11 and Centonze and Levy identified 84.6% of caregivers in north-central Florida were women.12 Notably, feminization is observed in animal rights activism fields13 and the veterinary medicine profession.14 An empathy perspective or ‘tuning-in with cats’ associated with an ecofeminist view, according to which women share a sense of inequity status with animals, and idea of conscious (political) choice have been proposed to understand this phenomenon.13 Feminization associated with cats specifically has been an emerging theme for more than three decades.15 Mertens16 found that women tend to engage more interactively with cats compared to men and children. However, while their interactions differ, they are not necessarily more appropriate, as supported by a more recent study with 90% of women participants showing varying degree of cat–human interaction styles including restraint (e.g. holding the cat).17 However, unowned cats vary greatly in their human contact seeking,2 and care is often provided from a distance with little or no physical interaction. Thus, it is more likely that feminization observed in this study and previous similar studies might be influenced by a woman’s active choice to be involved in cat population management and other aspects, more than by a ‘natural preference’ of cats for women, due to the way they interact with cats.

In terms of age, Slovak unowned cat caregivers are of similar approximate median age (40.1 years) as those in Florida in 1999, USA (47.4 years),12 but younger than U.S. caregivers of Jefferson County in 2023 (61.5 years).11 Other studies surveying attitudes toward unowned cats are usually targeted on the general population of the studied area (Australia,4,18 Belgium,5 Bulgaria,19 Canada,20 and Israel21) and not specifically at people working with this subpopulation of cats, and, thus, direct comparisons with these results are not appropriate. However, a recent Australian study reported a subgroup of respondents identified as semi-owners, thus people providing care to unowned cats but not considering themselves as their owners, being mostly female (83%) and younger on average than non-semi-owners (mean age of 45.5 vs. 49.5).22 Indeed, based on further demographic characteristics of our sample, at least some experience with unowned cats and providing volunteer care for unowned cats in colonies and own homes without being affiliated with any organization, suggest caregiver status for the majority of our respondents, similar to semi-ownership. Several studies already identified these stakeholders as an ideal target for human behavior change programs as part of successful cat population management5,18,22 with our results highlighting additional intervention topics.

Our study population did not distinguish between different domestic cat lifestyles – an evolving concept primarily based on a cat’s need for human contact and cohabitation.2,23 Within items grouped in our first factor, the vast majority of the respondents agreed with generalizing statements, not taking into account the spectrum of above-mentioned lifestyles, such as ‘All cats need a loving home’ or ‘All unowned kittens (cats up to 6 months of age) should go to a new home, to an owner’, confirming this ‘one approach fits all’ perception. However, within the same factor, the majority of respondents also disagreed with the statement ‘Not all cats can be pets’. A concerning finding highlighted within this factor was the respondents’ (lack of) knowledge of individual unowned cats’ needs and its incorporation within shelter intake decisions. Specifically, respondents agreed with the statement, ‘Unowned cats are always better off in a shelter or foster care than on the street’, while disagreeing with ‘Organisations helping unowned cats should decide which cats to take in’.

Although cat behavior research is a relatively new field, substantial scientific evidence already highlights significant individual differences among domestic cats. These differences are shaped by various proximate mechanisms, including genetic traits, developmental history, and physiological factors (for a review, see de Castro Travnik et al.24), with sociality and sociability being among the most extensively studied aspects (for a review, see Finka25). This evidence supports the need for an understanding of an individualized approach when working with cats, particularly in the rescue sector.2,23

The evident gaps in understanding domestic cats’ individual needs among our study population may be explained by the fact that most respondents were not affiliated with any formal organization, operated voluntarily, and received no financial compensation for their efforts. This suggests a lack of formal training and possibly limited motivation to pursue it. Future community engagement initiatives, including education programs, might not only address lacking awareness on domestic cat biology but, in effect, may also contribute to successful cat population control,26 as has been found in UK,27 US,28,29 Australia,30,31 or Spain.32

Within the second factor, most of our respondents agreed with statements regarding good practices of TNR such as ‘Cat neutering programs should also have a preparation and planning phase’ and least supported (and also less correlated according to factor loading) ‘Kittens (less than 6 months of age) should be part of a spay/neuter program, i.e. trap-neuter-release to the original or new location’. We suspect association with the findings of the first factor, where a generalizing approach has been applied to kitten management as well, i.e. each kitten should have an owner. This potential reluctance to accept the fact that not each kitten is fit for a rehoming scheme2,33 could have arisen due to lack of knowledge of the scientific evidence, suggesting a less successful socialization process beyond the important period of 2–7 weeks of age,34 and in some cases, this may be even ethically questionable.25

Our findings also revealed notable discrepancies in attitudes toward data collection and impact assessment. While respondents generally agreed with the statement, ‘Organisations helping unowned cats should collect information about the cats in their care and analyse it to measure the impact of their work’, they showed little interest in educational topics related to ‘data collection and analysis’ and ‘self-assessment and measuring impact of my work’. Given that these skills are essential for effective population management,1 their low prioritization in education may stem from a lack of understanding of the critical role data collection plays in assessing impact. To address this gap, future training programs for the Slovak cat population management community should focus on presenting these concepts in a clear, accessible, and practical manner, following cat population management guidelines.1,23

An apparent inconsistency was identified within the third factor, shelter management practices, and the fifth factor, comprised of a single statement: ‘Cats should remain in a shelter or foster care until the ideal home is found for them’. While the majority of respondents endorsed minimizing the length of stay in shelters, they simultaneously emphasized the necessity of a thorough adoption process and supported the principle of retaining cats in care until an optimal placement was secured.

This discrepancy may be attributed to respondents thinking of two different categories of cats, suitable for adoption and unsuitable ones, but could also be explained by social desirability bias, wherein respondents provide answers they perceive as ethically or professionally favorable.35 A clash of belief resulting in emotional discomfort known as cognitive dissonance,36 which has been previously discussed in a cat population management study,18 could also be behind the observed divergence in attitudes. Further investigation is warranted to assess the extent of this perceptual conflict and its emotional impact on individuals involved in unowned cat management. Future studies employing qualitative methodologies, such as focus group discussions, could provide deeper insight into these underlying attitudes and decision-making processes.

Euthanasia emerged as a key topic, with both statements addressing its acceptability in different scenarios loading within the fourth factor. Additionally, euthanasia decision-making was identified as the second most challenging aspect of working with unowned cats, while managing unwell cats ranked as the third most commonly selected area of educational interest.

Euthanasia in shelter and population management settings is widely discussed across various disciplines, with ongoing efforts to better understand its complexities,37,38 support ethical decision-making,39,40 and develop structured guidelines and algorithms.41,42 The observed variation in attitudes toward similar scenarios of feline suffering – such as prolonged convalescence in a stressful environment versus anticipated future suffering (e.g. long-term hospitalization with a guarded prognosis) – highlights the need for a more standardized approach to euthanasia decision-making.41

Regarding the cluster analysis results, the strong agreement or disagreement observed among a subset of respondents, the majority of which provide care for cats in colonies and are involved in fostering, may indicate a high degree of emotional investment among Slovaks involved in the care of unowned cats. Community cat caregivers often develop strong bonds with the animals they care for, comparable to those seen in traditional pet ownership.11,43 Their dedication is evident in significant financial contributions and personal sacrifices, such as foregoing vacations or prioritizing cat care over personal expenses.11 As mentioned earlier, the term ‘semi-ownership’ has been used to describe this unique phenomenon.18,22 A proposed downside of this relationship is feeding without neutering, what may lead to excessive breeding18 and even over-ideal body condition in unowned cats44; however, direct evidence to support these links is currently lacking.

Given the parallels between caregiver-pet cat and caregiver-unowned cat relationships, as well as the impact of individual caregiver characteristics on interaction styles and decision-making,17,45 successful cat population management strategies must consider the dynamics of the cat-caregiver unit, a trend in line with the holistic feline medicine approach.46 This is particularly relevant when aiming to influence human behavior change, which is a key component of effective, sustainable management programs.5,22 The promising tool for achieving behavior change, which has already been applied in cat-focused research,22,47 is Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Behavior system, or COM-B.48 Although our survey was not initially designed to incorporate this specific analysis, our findings suggest the presence of certain capability, opportunity, and motivation-related factors influencing behavior change within our study population. Specifically, the majority of respondents did not report significant barriers related to mental or physical capacity, nor environmental constraints on learning. Additionally, our results indicate a strong interest in further education across various topics, highlighting motivation as a key determinant. Thus, in further studies attempting to answer the ‘how?’ question, i.e. actions undertaken as part of unowned cat management in Slovakia, COM-B analysis may assist in refining the barriers of targeted behavior changes.

The two major limitations of this study are the relatively small, self-selected sample (N = 276) and internet survey data collection. We acknowledge that for this reason, our findings may not be accurately representing the whole population working with unowned cats in Slovakia. Indeed, a younger survey demographic suggests older community cat caregivers may have limited internet access and possibly be underrepresented here, and given the small sample size, future research should combine online surveying with door-to-door data collection. However, it is important to emphasize that the aim of this study was to provide an initial snapshot and generate a descriptive report about Slovaks associated with unowned cats. We believe this study can serve as a foundation for further research in Slovakia and may inspire similar investigations in countries with comparable historical and cultural contexts, where the lack of such data impede effective cat population management.

Conclusion

This study is the first of its kind to characterize the population of Slovaks involved in the care of unowned cats. While their basic demographic profiles are similar to community cat caretakers in other countries, most of the women in this study act independently when fostering or caring for colony cats. These findings suggest a commitment to cat welfare that aligns with the concept of semi-ownership, a designation not yet formally recognized in Slovak legislation. Generalizing and conflicting attitudes toward cat population management practices but interest and ability to participate in further education suggest that targeted training programs might increase efficacy of unowned cat management. The course content should not only focus on cat biology and lifestyles but also applied basics of data collection, analysis, and measuring impact, with examples of how these influence financial income and decision-making. Since Slovak municipalities are legally obligated to care for unowned animals, but their responsibilities are not clearly defined, our findings suggest that offering free training courses for volunteers could be an effective policy to enhance urban cat management. Monitoring short- and long-term influences of such training programs could then provide the groundwork for legislative and policy changes in favor of structured and a systemic approach to cat population management in Slovakia.

Author contributions

Noema Gajdoš Kmecová: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Ann Enright: Writing – Original draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Daniela Takáčová: Writing – Review & Editing. Ivana Božíková: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology. Phil Assheton: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge International Cat Care for inspiring this research by their own survey ‘Working with unowned cats’, Dr. Lauren Finka for her valuable insights during the development of the survey, Slovak NGO ‘Zvierací Ombudsman’ (Animal ombudsman) for their assistance in dissemination of the online survey, and all participants who were willing to share with us their attitudes, opinions, and comments.

Author notes

Material contained in this manuscript has been covered in a diploma thesis of IB supervised by NGK titled ‘Súčasný stav manažmentu populácie mačiek na Slovensku’.

References

| 1. | International Companion Animal Management Coalition. Humane Cat Population Management Guidance. 2011. https://www.icam-coalition.org/download/humane-cat-population-management-guidance/. Accessed April 11, 2025. |

| 2. | Halls V, Bessant C. Managing cat populations based on an understanding of cat lifestyle and population dynamics. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2023;2(S1):58. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.58 |

| 3. | Halls V, Bessant C. Identifying solutions for ‘inbetweener’ cats. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2023;2(S1):59. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.59 |

| 4. | Rand J, Scotney R, Enright A, Hayward A, Bennett P, Morton J. Situational analysis of cat ownership and cat caring behaviors in a community with high shelter admissions of cats. Animals. 2024;14(19):2849. doi: 10.3390/ani14192849 |

| 5. | De Ruyver C, Abatih E, Villa PD, et al. Public opinions on seven different stray cat population management scenarios in Flanders, Belgium. Res Vet Sci. 2021;136:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2021.02.025 |

| 6. | FEDIAF European Pet Food. FEDIAF Annual Report 2024. 2024. https://europeanpetfood.org/about/annual-report/. Accessed April 11, 2025. |

| 7. | FEDIAF European Pet Food. FEDIAF Annual Report 2023. 2023. https://europeanpetfood.org/about/annual-report/. Accessed April 11, 2025. |

| 8. | FEDIAF European Pet Food. FEDIAF Annual Report 2022. 2022. https://europeanpetfood.org/about/annual-report/. Accessed April 11, 2025. |

| 9. | Natoli E, Ziegler N, Dufau A, Pinto Teixeira M. Unowned free-roaming domestic cats: reflection of animal welfare and ethical aspects in animal laws in six European countries. J Appl Anim Ethics Res. 2019;2(1):38–56. doi: 10.1163/25889567-12340017 |

| 10. | State Veterinary and Food Administration of the Slovak Republic. Schválené prevádzkarne (EU) – Karanténne stanice a útulky pre spoločenské zvieratá. Zoznam schválených karanténnych staníc a útulkov podľa §39 ods.11 zákona 39/2007 Z.z. vplatnom znení. https://zoznamy.svps.sk/default.asp?typ=zoznam-vet-schvalene&cmd=resetall&Zoznamy=ostatne&Sekcia=46&Cinnost=0&Podsekcia=0. Accessed April 11, 2025. |

| 11. | Neal SM, Wolf PJ. A cat is a cat: attachment to community cats transcends ownership status. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2023;2(1):62. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.62 |

| 12. | Centonze LA, Levy JK. Characteristics of free-roaming cats and their caretakers. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;220(11):1627–1633. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.220.1627 |

| 13. | Gaarder E. Where the boys aren’t: the predominance of women in animal rights activism. Fem Form. 2011;23(2):54–76. doi: 10.1353/ff.2011.0019 |

| 14. | Lofstedt J. Gender and veterinary medicine. Can Vet J. 2003;44(7):533–535. |

| 15. | Turner DC. A review of over three decades of research on cat-human and human-cat interactions and relationships. Behav Process. 2017;141:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2017.01.008 |

| 16. | Mertens C. Human-cat interactions in the home setting. Anthrozoos. 1991;4(4):214–231. doi: 10.2752/089279391787057062 |

| 17. | Finka LR, Ripari L, Quinlan L, et al. Investigation of humans individual differences as predictors of their animal interaction styles, focused on the domestic cat. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12128. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-15194-7 |

| 18. | Zito S, Vankan D, Bennett P, Paterson M, Phillips CJC. Cat ownership perception and caretaking explored in an internet survey of people associated with cats. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133293 |

| 19. | Vasileva I, McCulloch SP. Attitudes and behaviours towards cats and barriers to stray cat management in Bulgaria. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2024;27(4):746–760. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2023.2186787 |

| 20. | Van Patter L, Flockhart T, Coe J, et al. Perceptions of community cats and preferences for their management in Guelph, Ontario. Part I: a quantitative analysis. Can Vet J. 2019;60(1):41–47. |

| 21. | Finkler H, Terkel J. The contribution of cat owners’ attitudes and behaviours to the free-roaming cat overpopulation in Tel Aviv, Israel. Prev Vet Med. 2012;104(1–2):125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.11.006 |

| 22. | Ma GC, McLeod LJ, Zito SJ. Characteristics of cat semi-owners. J Feline Med Surg. 2023;25(9):1098612X231194225. doi: 10.1177/1098612X231194225 |

| 23. | Sparkes AH, Bessant C, Cope K, et al. ISFM guidelines on population management and welfare of unowned domestic cats (Felis catus). J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15(9):811–817. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13500431 |

| 24. | de Castro Travnik I, de Souza Machado D, da Silva Gonçalves L, Ceballos MC, Sant’anna AC. Temperament in domestic cats: a review of proximate mechanisms, methods of assessment, its effects on human – cat relationships, and one welfare. Animals. 2020;10(9):1–23. doi: 10.3390/ani10091516 |

| 25. | Finka LR. Conspecific and human sociality in the domestic cat: consideration of proximate mechanisms, human selection and implications for cat welfare. Animals. 2022;12(3):298. doi: 10.3390/ani12030298 |

| 26. | Ramírez Riveros D, González-Lagos C. Community engagement and the effectiveness of free-roaming cat control techniques: a systematic review. Animals. 2024;14(3):492. doi: 10.3390/ani14030492 |

| 27. | McDonald JL, Clements J. Engaging with socio-economically disadvantaged communities and their cats: human behaviour change for animal and human benefit. Animals. 2019;9(4):175. doi: 10.3390/ani9040175 |

| 28. | Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. An examination of an iconic trap-neuter-return program: the newburyport, massachusetts case study. Animals. 2017;7(11):81. doi: 10.3390/ani7110081 |

| 29. | Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. A case study in citizen science: the effectiveness of a trap-neuter-return program in a Chicago neighborhood. Animals. 2018;8(1):14. doi: 10.3390/ani8010014 |

| 30. | Cotterell JL, Rand J, Barnes TS, Scotney R. Impact of a local government funded free cat sterilization program for owned and semi-owned cats. Animals. 2024;14(11):1615. doi: 10.3390/ani14111615 |

| 31. | Cotterell J, Rand J, Scotney R. Urban cat management in Australia – evidence-based strategies for success. Animals. 2025;15(8):1083. doi: 10.3390/ani15081083 |

| 32. | Luzardo OP, Vara-Rascón M, Dufau A, Infante E, del Mar Travieso-Aja M. Four years of promising trap–neuter–return (TNR) in Córdoba, Spain: a scalable model for urban feline management. Animals. 2025;15(4):482. doi: 10.3390/ani15040482 |

| 33. | Halls V, Ellis SLH, Bessant C. Outcomes for kittens born to free-roaming unowned cats. J Shelter Med Community Anim Health. 2023;2(S1):57. doi: 10.56771/jsmcah.v2.57 |

| 34. | Karsh EB, Turner DC. The human-cat relationship. In: Turner DC, Bateson P (Editors). The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1988, pp. 157–177. |

| 35. | Meagher RK. Observer ratings: validity and value as a tool for animal welfare research. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2009;119(1–2):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2009.02.026 |

| 36. | Festinger L. Cognitive dissonance. Sci Am. 1962;207(4):93–106. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1062-93 |

| 37. | Anderson KA, Brandt JC, Lord LK, Miles EA. Euthanasia in animal shelters: management’s perspective on staff reactions and support programs. Anthrozoos. 2013;26(4):569–578. doi: 10.2752/175303713X13795775536057 |

| 38. | Persson K, Selter F, Neitzke G, Kunzmann P. Philosophy of a ‘good death’ in small animals and consequences for euthanasia in animal law and veterinary practice. Animals. 2020;10(1):124. doi: 10.3390/ani10010124 |

| 39. | Cooney K, Kipperman B. Ethical and practical considerations associated with companion animal euthanasia. Animals. 2023;13(3):430. doi: 10.3390/ani13030430 |

| 40. | Spitznagel MB, Marchitelli B, Gardner M, Carlson MD. Euthanasia from the veterinary client’s perspective: psychosocial contributors to euthanasia decision making . Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2020;50(3):591–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2019.12.008 |

| 41. | International Companion Animal Management Coalition. The Welfare Basis for Euthanasia of Dogs and Cats and Policy Development. https://www.icam-coalition.org/download/the-welfare-basis-for-the-euthanasia-of-dogs-and-cats-and-policy-development/. Accessed April 11, 2025. |

| 42. | British Veterinary Association. BVA Guide to Euthanasia. 2016. https://www.bva.co.uk/media/2981/bva_guide_to_euthanasia_2016.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2025. |

| 43. | Scotney R, Rand J, Rohlf V, Hayward A, Bennett P. The impact of lethal, enforcement-centred cat management on human wellbeing: exploring lived experiences of cat carers affected by cat culling at the Port of Newcastle. Animals. 2023;13(2):271. doi: 10.3390/ani13020271 |

| 44. | Marston LC, Bennett PC. Admissions of cats to animal welfare shelters in Melbourne, Australia. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2009;12(3):189–213. doi: 10.1080/10888700902955948 |

| 45. | Vonk J, Bouma EMC, Dijkstra A. A time to say goodbye: empathy and emotion regulation predict timing of end-of-life decisions by pet owners. Hum Anim Interact Bull. 2022;13(1):146–165. doi: 10.1079/hai.2022.0013 |

| 46. | Eigner DR, Breitreiter K, Carmack T, et al. 2023 AAFP/IAAHPC feline hospice and palliative care guidelines. J Feline Med Surg. 2023;25(9):1098612X231201683. doi: 10.1177/1098612X231201683 |

| 47. | Delgado M, Marcinkiewicz E, Rhodes P, Ellis SLH. Identifying barriers to providing daily playtime for cats: a survey-based approach using COM-B analysis. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2024;280:106420. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2024.106420 |

| 48. | Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(42):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 |

Footnotes

a How you can help cats in need (‘Ako môžete pomôct mačkám v núdzi’). Mačky SOS NGO, https://www.mackysos.sk/pomozte.mackam, accessed April 10, 2025.

b Support us (‘Podporte nás’). Srdce pre mačky NGO, https://www.srdcepremacky.sk/podporte-nas/, accessed April 10, 2025.

c How to help (‘Ako nám môžete pomôcť’) Vysnené mačky NGO, https://www.ozvysnenemacky.sk/#how_to_help, accessed April 10, 2025.