ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

The Twenty Highest Priority Questions to Answer to Improve Access to Veterinary Care

Sharon Pailler1, Sloane M. Hawes2, Kendall E. Houlihan3, Janet Hoy-Gerlach4, Molly Sumridge1*, Emily McCobb5, Sheila Segurson6, Margaret R. Slater1, Kiyomi M. Beach7, Brittany Watson8, Apryl Steele9, Veronica H. Accornero1, Jason B. Coe10, Arnold Arluke11, Amanda Arrington12, Lauren A. Bernstein13, T’ Fisher14, William K. Frahm-Gillies15, Inga L. Fricke16, Jennifer L. Scarlett17, Douglas J. Spiker18 and Jim Tedford19

1Department of Strategy and Research, American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, New York, NY, USA; 2Research and Development, Companions and Animals for Reform and Equity, Baltimore, MD, USA; 3Animal Welfare Division, Public Policy SBU, American Veterinary Medical Association, Schaumburg, IL, USA; 4Open Door Veterinary Collective, Grand Rapids, OH, USA; 5School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, CA, USA; 6Maddie’s Fund, Pleasanton, CA, USA; 7Vetbulance Community Care, Atlanta, GA, USA; 8Shelter Medicine and Community Engagement, University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 9Dumb Friends League, Denver, CO, USA; 10Veterinary Centers of America (VCA) Canada Chair in Relationship-Centered Veterinary Medicine, Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, Guelph, Ontario, Canada; 11Emeritus of Sociology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA; 12Access to Care, Humane Society of the United States, Washington DC, USA; 13College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN, USA; 14University of Tennessee Program for Pet Health Equity, Knoxville, TN, USA; 15Access Veterinary Care, Minneapolis, MN, USA; 16McKamey Animal Center, Chattanooga, TN, USA; 17San Francisco Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SF SPCA), San Francisco, CA, USA; 18BluePearl Pet Hospital, Clearwater, FL, USA; 19The Association for Animal Welfare Advancement, Surprise, AZ, USA

Abstract

The veterinary and animal welfare fields are tasked to respond to the urgent need for improved access to veterinary care (AVC) for underserved populations across the nation. We conducted an initial survey and an iterative selection of priority questions using a modified Delphi method among a committee of experts in AVC to identify the 20 questions with the greatest potential to inform and advance our crucial work in AVC, if answered. The results of this project produced expansive questions focused on equity, engaging communities and pet owners, supporting practitioners, and delivering care. We then provided a landscape of existing research with the goal of supporting academics, practitioners, and communities in prioritizing their research and program development agendas, ultimately advancing AVC efforts around the country.

Keywords: priority setting; research agenda; access to veterinary care; animal welfare

Citation: Journal of Shelter Medicine and Community Animal Health 2025, 4: 106 - http://dx.doi.org/10.56771/jsmcah.v4.106

Copyright: © 2025 Sharon Pailler et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 4 June 2024; Revised: 13 January 2025; Accepted: 13 January 2025; Published: 3 March 2025

Reviewers: Lexis Ly, Kevin Horecka

Correspondence: *Molly Sumridge, Director, Research, Department of Strategy and Research, American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, New York, NY, USA. Phone: (406) 475-0279, Email: molly.sumridge@aspca.org

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Veterinary care is critical to animal welfare,1 yet millions of pet owners face a multitude of barriers that prevent them from accessing veterinary care for their pets.2,3 These barriers include cost of care;4 physical accessibility for disabled owners and owners without transportation;5–9 the need for more accessible information about care and services, including the importance of regular veterinary care and options for low-income owners;2 lack of available veterinarians in underserved and rural areas;10,11 nuanced cultural and social factors, including the presence of language or cultural differences; and fear of stigma experienced by marginalized groups.12–15 Lack of access to veterinary care (AVC) is an important issue not only for underserved pets and pet owners but also for the veterinary field, local communities, animal shelters/rescues, and society in general.16,17

Issues surrounding AVC have gained more attention in recent years, and several initiatives dedicated to improving AVC have emerged in the last decade, including work by major national veterinary and animal welfare organizations and coalitions focused specifically on AVC. Despite increased attention and efforts to improve AVC, many questions remain surrounding how to best construct and deliver highly effective programs that increase accessibility of veterinary care for pets.4,16,18,19 There is, therefore, an immense need for research in this area.4,18,19

Other fields have leaned on collaborative efforts among researchers, practitioners, and policy makers to identify high priority research topics through proposing, collectively discussing, and selecting the most important questions to answer to help the field progress.20–22 In the development of best practices, when there is a lack of empirical evidence, expert opinion generated by a panel of experts in the field is considered a foundational starting place.23 Given the state of research in AVC, convening a panel of experts is an appropriate first step in developing an evidence-based assessment.23 Our aim was to thus harness the expertise of the AVC community to compile a list of questions with the greatest potential to inform and advance our work in AVC, focusing on questions that have not yet been fully answered and were answerable through research. The goal of creating this list was to enable AVC researchers to focus on the questions that will have the greatest impact to establish a stronger connection between impactful research in AVC and practical implementation of findings. This list can serve as valuable guidance for researchers and research funding organizations, helping them focus their efforts on answering the questions that will have the greatest impact, ultimately advancing AVC, and improving welfare of companion animals across the country.

Methods

Initial survey

Engaging patient and public stakeholders in health care research has demonstrated positive impacts on the development of user-focused research objectives and questions as well as enhanced communication and implementation of research findings.24 To engage the AVC community’s interprofessional subject-matter experts in identifying questions of interest, we administered an online survey asking respondents to contribute one to three questions that they believe would have the greatest potential to improve AVC if answered (Appendix 1). The initial survey and framing of the survey question were similar to other studies identifying priority research questions22,25 and enabled us to identify a broad set of questions that were relevant to the AVC community. Specifically, we used an adaptation of the Delphi Method,25,26 which entails convening a group of experts who provide input and feedback in response to multiple rounds of questionnaires; their responses are aggregated and shared with the group after each round to prompt further analysis.

We received Institutional Review Board (IRB) review and exemption for this study from Advarra IRB on October 7th, 2021. The initial survey was piloted among 10 employees of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) with roles ranging from veterinarians and veterinary technicians to social worker, client services representatives, and animal behaviorists. This was done to ensure ease of comprehension and completion. A steering committee of 18 AVC subject-matter experts representing the diverse threads of AVC work were recruited through professional association, networking within the animal welfare nonprofit community and snowball sampling. This steering committee was formed to collect a wide range of disciplines, roles and types of involvement to shape and disseminate the survey, and to prioritize questions solicited via the survey. These experts represented multiple fields including veterinary medicine, social work, animal sheltering, and community outreach and represented various types of institutions including academia, government, nonprofit, and private and corporate veterinary practice. This committee disseminated the survey via professional listservs and networks targeting the AVC community with the aim of gathering questions from actors working in a variety of contexts including veterinarians, social workers, academics, government officials, animal shelter staff, and the broader animal welfare community. Survey respondents were also asked to share the link with their colleagues who work in AVC. Responses were collected from October 12th, 2021, to November 12th, 2021. Survey respondents consented to participation, acknowledging that their survey responses are confidential. De-identified survey responses are available upon reasonable request for additional research.

Question list refinement

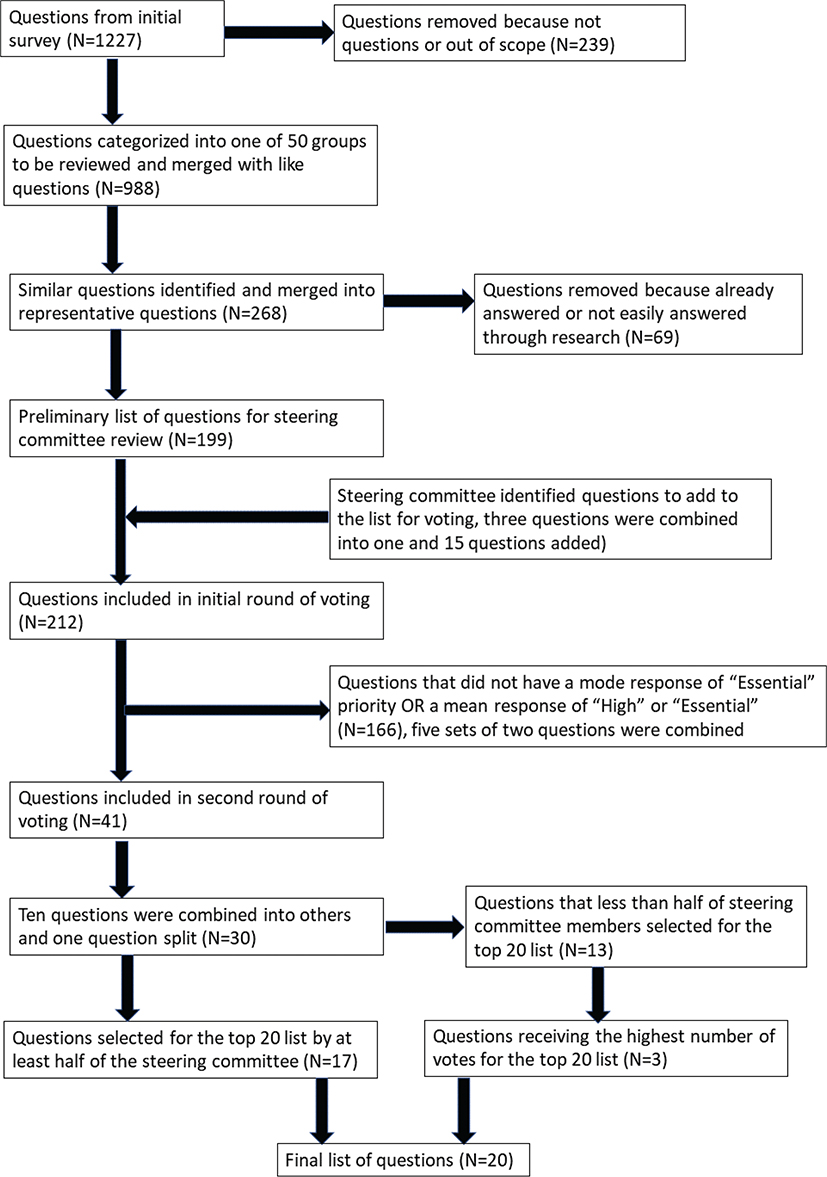

The initial survey of the AVC community generated 1,227 questions from 462 survey respondents. Figure 1 outlines the steps taken to identify and prioritize research questions and the number of questions remaining after each step. The lead author reviewed the initial list of responses to eliminate those that (1) were not questions and where a question could not be derived from the respondent’s stated explanation (e.g. ‘Access to care’ and ‘Payment plans’); (2) did not pertain specifically to AVC (e.g. ‘Why do vet techs continue to scruff cats?’); or (3) were specific to the ASPCA (e.g. ‘How can the ASPCA improve access to vet care for rabbits in NYC?’). Eliminated responses were reviewed by two additional colleagues for consensus prior to removal. The response remained on the list if there was disagreement about elimination; 239 responses were removed from the initial list.

The lead author compiled and reviewed the remaining 988 questions, developed and defined categories based on the question content, and categorized similar questions to identify questions that could be combined. Each question and its preliminary categorization were reviewed by one of six ASPCA colleagues to confirm appropriate and consistent categorization based on the definition of that category. The lead author then identified duplicate questions within each category and selected one question to represent duplicate questions. Questions such as ‘Would many pet owners be able to keep their pet in their home if they had veterinary care available and affordable for them?’ and ‘Could AVC prevent owner surrenders to shelters?’ were combined. An ASPCA colleague and a coauthor reviewed each set of combined questions to confirm they should be combined. In cases where there was disagreement, questions were not combined. After merging similar questions, 268 questions remained.

We solicited the initial set of questions from the broader AVC interprofessional community to generate questions from those who are actively engaged in the space; most questions were submitted by individuals who are unfamiliar with constructing research questions. Therefore, throughout the categorization and combining processes, questions from the initial list needed to be refined to improve clarity and to more easily be operationalized to address AVC research gaps. The lead author refined question wording, and two ASPCA colleagues and coauthors reviewed the refined wording of each modified question to ensure accurate representation of the original questions.

Finally, to arrive at a list of questions that were (1) highly relevant to advancing AVC, (2) had not already been adequately addressed, and (3) were answerable through empirical research methods, the lead author reviewed questions to identify those that have been addressed through recent research (e.g. ‘What are barriers to accessing veterinary care?’ is well covered in the AVC Coalition’s 2018 report16) and those that could not be addressed using empirical research methods. Some questions were reworded to represent a question addressable through research, for instance, ‘How do we better respond to and engage clients?’ was revised to ‘What strategies are most effective for engaging clients in veterinary care for their pets?’ An ASPCA colleague and a coauthor reviewed those that were flagged for removal, and in cases where there was disagreement about whether the question should be removed, a second colleague and a coauthor reviewed the question to confirm it should be removed or remain on the list. An additional 69 questions were removed. A penultimate list of 199 questions was shared with the steering committee for feedback and to solicit additional questions. Steering committee members suggested three questions be merged into one and contributed an additional 15 questions; a final list of 212 questions was prioritized.

Prioritization

The steering committee of AVC experts completed two rounds of voting via online surveys to identify top priority questions. In the first round of voting, steering committee members rated the priority level of the 212 questions on a Likert scale27 (not a priority, low priority, moderate priority, high priority, essential priority, don’t know) based on each question’s potential to inform and advance impactful research in AVC. Each steering committee member’s question rating was given a value of 1–5 (1 = ‘Not a priority’ and 5 = ‘Essential priority’), and the mean, median, and mode response of each question were calculated.

Forty-six of the 212 questions had a median or mode response = 5 (‘Essential priority’) or a mean ≥ 4 (‘High priority’); these 46 questions were selected for the next round of voting. During the initial round of voting, steering committee members suggested that five of the 46 questions be combined into other questions, thus 41 questions remained for the final round of voting.

In the second and final round, steering committee members were asked to select up to 20 questions from the list of 41 that they thought would have the greatest potential to inform and advance our research in AVC, if answered. Steering committee members also provided explanations as to why they did or did not select a given question for their top 20. During the second round of voting, steering committee members identified an additional 10 questions that could be combined into others and one that could be split, thus the list of 41 questions was reduced to 30 (Fig. 1). Of the 30 questions, 17 were selected by at least half of the respondents as one of the 20 highest priority questions. Steering committee members then had the opportunity to review other steering committee members’ selections and explanations and confirm the list of 17 questions for inclusion on the final list of priority questions. After reviewing and confirming the list of 17 questions, steering committee members picked their top two questions from the remaining 13 questions that did not make the final list. A question was assigned two points when a committee member selected it as the number one question and one point when it was selected as the number two question. The three questions with the highest number of points were added to the 17 to complete a list of 20 questions with the greatest potential to inform and advance our work in AVC, if answered.

Twenty highest priority questions

Table 1 includes the 20 highest priority research questions selected by the steering committee. These are not listed in order of importance but are sequenced by similar and/or related questions.

Exploring the 20 questions

Given the complexity of AVC research and the breadth of the questions asked, we provide examples and briefly discuss caveats, related work, and other considerations associated with each question, in turn.

Defining AVC

1) How do we define equitable access to veterinary care?

Because lack of AVC is a broad and emerging issue that involves numerous parties from different fields with different roles, ideas around ‘equitable’ and ‘access to veterinary care’ and what they look like vary and are sometimes conflicting. To conduct meaningful research, we must define the problem we seek to address to provide a common understanding of the problem and the proposed solutions. This understanding not only helps to clarify the specific purpose of research in AVC but also advances the field. This work is already being undertaken in the human health and social science fields28 and is an opportunity to bridge these definitions with the veterinary care field. To develop a shared understanding, researchers could conduct qualitative research with various stakeholders, such as veterinary staff and underserved pet owner communities both to elucidate the amount of variation in what ‘equitable’ and ‘access to veterinary care’ mean, as in building off the works of Robert et al. to define ‘underserved’29 and Pasteur et al. in evaluating working definitions in AVC,30 and to further develop and refine inclusive and broadly applicable working definitions of these terms. Working definitions may vary from one project to another, depending upon the stakeholder group(s) involved. From the outset of any research initiative it is critical to determine and provide definitions to accurately frame, interpret, and use findings of that research.

2) What are the most effective mechanisms to identify those who need care?

Building upon the prior question, identifying ‘those who need care’ requires first defining ‘equitable’ and ‘access to veterinary care.’ Once populations have been defined, service providers need to be able to identify those pet owners and their specific barriers in order to take actions to increase AVC. Some existing research has explored methods to identify areas of need based on proximity to veterinary services,8 poverty,31 or language barriers.32,33 Developing additional mechanisms to identify populations that are not receiving veterinary care is an important gap to fill. This topic is highly complex, given the rich diversity of communities that will require different geographic, financial, and knowledge-based solutions, and different mechanisms to identify those who need care, but are not able to access it.

3) What are the most effective mechanisms to increase access in locations with little to no veterinary services?

Communities with little to no veterinary services are particularly challenging environments to enhance access to care due to the lack of existing infrastructure to optimize/improve access. Some geographic regions lack sufficient veterinary professionals to serve the surrounding area,8 or the pet-owning population cannot access veterinary care due to lack of transportation or affordability.12,34 Locations with little to no veterinary services can occur in rural and urban areas alike, and each of these contexts will face different challenges relating to distance from pet care services, transportation barriers, and clinic hours of operation. Research by Neal and Greenberg8 as well as Bunke and colleagues34 is helpful for researchers to identify specific veterinary care deserts and their unique characteristics and subsequently develop and test potential mechanisms to increase access to care in a given geographic area. There are several promising strategies, such as mobile clinics that provide low-cost spay and neuter services to rural and underserved areas,32 in-home treatments that an owner can independently provide for their pets instead of traveling long distances to maintain care for health conditions requiring repeat treatments,35 and telehealth for general health consultations to non-life-threatening sick appointments for pets whose owners are lacking access to transportation,31 all of which could be highly effective at increasing care in areas with little to no veterinary services when the state’s practice act and federal law permit. Continuing to identify applications to strategies like these and determining their financial viability are critical, as well as identifying strategies that may be unique to specific populations such as tribal communities and rural areas without major infrastructure. Looking to alternate business models can also provide mechanisms to provide veterinary care in geographies with limited AVC.36 These approaches should be investigated to see where, when, and how they are most effective, and new strategies developed and tested to increase access to care across a variety of veterinary deserts.

4) What are the social and cultural barriers to seeking out veterinary care?

Pet owners face barriers due to differences in language and communication, awareness of veterinary care, and perceptions of adequate veterinary care.2,4 Service providers, however unintentionally, reinforce these barriers through their own cultural biases and misunderstanding.2,37 Institutional barriers further foster social and cultural divides. For example, low-income, African American pet owners in North Carolina distrusted the intentions of humane societies and veterinarians, even when their services were discounted because of the state’s recent history of forcibly sterilizing young women of color.12 Because social and cultural barriers are complex and intersectional,38 successful implementation of AVC programs depends upon addressing social and cultural barriers, and more research is needed in this space. Future research could build upon work such as the Pets for Life program37,39 that provides direct care services to underserved populations, as well as mentoring community organizations to provide veterinary services to underserved populations. Additionally, further work is needed in identifying which groups of pet owners from a given community are still not receiving veterinary care and why, identifying the cultural barriers that restrict knowledge of availability and understanding of the impact of services, and then testing programs to reduce these barriers to care.

5) What AVC approaches result in the greatest use of services by underserved/marginalized communities?

Offering services that increase access to care, on its own, does not guarantee uptake by the pet owners who need care the most. Once a population in need has been identified, practitioners must then develop legitimate and trustworthy channels to encourage those pet owners to seek veterinary services. Research can provide the tools to do this. For example, a study by Arluke and Rowan12 found that door-to-door visits by outreach workers from a local shelter were the most successful way to engage pet owners. Uptake of veterinary services depends on many factors: language barriers, recognition of the importance of veterinary care, rapport and trust with veterinary providers, etc. Thus, the AVC approaches that result in the greatest use of services, how and why, will differ from one community to another.

Community-driven participatory research and research that evaluates existing models that seek to engage underserved communities are vital. Pets for Life, for example, removes structural barriers embedded within inequalities through directly connecting pet owners and pets with veterinary care and mentoring local organizations and veterinarians in community outreach.17 The Open Door Vet Collective provides the veterinary community with in-person and virtual continuing education and certificate programs and also conducts research on topics such as payment options that reduce financial barriers to AVC.40 The Tufts at Tech clinic develops skills and comfort with community medicine among veterinary and technician students by providing veterinary care delivered by students as well as publishing the results of their care and support in their community.18 Companions and Animals for Reform and Equity prioritizes providing marginalized pet owners with direct care and deconstructs cultural and societal influences on underserved communities and their access to care.38 Additional research on these and other community-based programs designed to increase access to care will help to build a foundation of work that practitioners can lean on to effectively engage and partner with their local underserved communities.

6) How do we increase preventative veterinary care access and utilization?

Twenty-three per cent of pet owners reported that they are unable to receive preventative (wellness/vaccine) veterinary care for their pets leaving them susceptible to illnesses, such as parvovirus and heartworm, that are expensive to treat and potentially fatal.16 Preventing these illnesses from the outset could prevent surrenders and euthanasia of pets whose owners cannot afford to seek veterinary care when their pet is sick. Increasing preventative veterinary care access and utilization could also decrease demands on an overwhelmed veterinary care system. Very little work has been done in this area to date. To increase preventative veterinary care access and use, researchers could conduct analysis on community knowledge of physical access to and the perceived value of preventative care to determine how to help pet owners and communities increase knowledge and uptake of preventative care services.

7) What types of veterinary services are most needed?

Identifying the veterinary services that are most needed would allow research, resources, and programs to focus on improving accessibility to those services. One approach could be to identify the most common conditions that underserved pets face and subsequently focus research on cost-effective treatments or prevention. A study by Hohenhaus41 reports the most common conditions in cats and dogs that were referred to the Schwarzman Animal Medical Center’s Rescue Program between 2020 and 2022, and the costs of treatment provided. Another approach to identify the types of veterinary services most needed could include a national review of conditions commonly encountered and treated at locations of veterinary practices, large-scale multi-location veterinary hospitals, animal welfare organizations, subsidized veterinary care programs, etc. There may be a variety of perspectives on which types of veterinary services are needed most, particularly in underserved communities. Inherent to this question is how ‘need’ is defined and who defines it; thus, it is also important for research to specifically focus on the needs and approaches that would be most impactful for a given community.42–46

8) What is the basic standard of care for common conditions?

Standard of care is a legal term of art for the level of care that a reasonably competent veterinarian would practice under similar circumstances. With few exceptions, the acceptable standard is established through expert testimony based on education, training, and experience of a qualified expert. Establishing a well-defined and evidence-based meaning for a basic level of acceptable care and guidance on how to manage those conditions could position veterinarians to diversify treatment options offered with confidence that their clinical recommendations could be defended in case of legal or regulatory action.47 A basic level of acceptable care may also serve as a foundation for research on effectiveness of lower cost treatments, helping to identify how we can make veterinary care more affordable for underserved pet owners (Question #18). This may simultaneously address some of the obstacles to the veterinary field in increasing access to care (Question #14). Defining a basic level of acceptable care should include many considerations and be informed by scientific evidence, ethics, animal welfare science, and clinical applicability.47 Clinical research comparing outcomes of different treatment approaches would additionally help to inform further spectrum of care (SoC) options. Generating consensus among experts through a robust approach such as the Delphi process25,26 is another potential approach to identify a basic level of acceptable care.

9) How do outcomes of spectrum of care and incremental veterinary care approaches differ from outcomes of traditional approaches?

SoC is providing a suite of options to family members and weighing those options with respect to time, financial, and quality of life constraints.48 Incremental veterinary care (IVC) is a tiered case management approach that sequences treatment options, beginning with simple, basic treatments, and advancing to more sophisticated and costly treatments as needed.16,49 SoC and IVC facilitate effective and less costly treatment by using less resource intensive diagnostic information, having clear and documented communication with the pet owner, and treating based on the contextual situation.50 Evidence is necessary to identify which conditions are most appropriate to treat through informed-client consent SoC or IVC approaches, and the appropriate diagnostic and treatment options for those conditions. To encourage adoption of SoC and IVC approaches, veterinary medicine needs more research that demonstrates that these approaches can be just as effective, if not more effective than traditional approaches. Equipped with evidence of what conditions can be treated effectively with SoC and IVC and how to implement SoC and IVC in different contexts and settings, veterinarians can more confidently offer more diverse and lower cost treatments in their practices.

10) What services are most often declined due to price?

Knowing which services are most often declined due to price will help to focus research where there is the greatest need for development of low-cost treatment options. Veterinary medical researchers can then develop and test the effectiveness of lower cost alternatives compared with traditional approaches (Question #9). When armed with information about the effectiveness of lower cost services, practitioners will be able to confidently offer them to clients who decline services due to price. Several papers reported that nonspecialized and outpatient treatment for pyometra, a common potentially deadly uterine infection, was highly effective,51–53 expanding evidence-informed spectrum of treatment options that providers can offer to treat pyometra. Research on the effectiveness of options at a lower cost for additional key health issues is important for increasing access to care. To identify the services that are most often declined due to price, researchers could collaborate with local veterinary clinics to track those services that are declined and why. Results could similarly inform the question ‘What types of veterinary services are most needed’ (Question #7) and identify where there may be a need for preventative medicine and/or different mechanisms for financing services. While there may be similarities across the US, services that are often declined due to price could vary across regions or communities, so it is important to consider local contexts.

11) What conditions more frequently lead to economic euthanasia?

Economic euthanasia is the decision to euthanize when a pet owner cannot afford to provide care despite available treatment with a good prognosis. Research identifying which conditions most frequently lead to economic euthanasia will help to focus future research efforts on opportunities for prevention, developing alternative, lower cost treatments, and creating mechanisms to finance treatment, such as pet insurance or payment plans.54–56 This will enable practitioners to adopt research-backed approaches that expand access to care for pets that would not have otherwise received it.

12) How do we make euthanasia accessible if indicated?

Accessibility to euthanasia services for animals that are suffering, have terminal conditions, or pose significant risks to public safety is a critical need for people who love their pets and do not want them to suffer. When pet owners are unable to access euthanasia services, their pets may endure prolonged suffering, or pet owners may use inhumane methods of euthanasia. Pet owners may not have access to euthanasia because of cost, availability of veterinarians, lack of transportation, or trust in someone to assist with euthanasia decisions. Some pet owners, especially those who have not had AVC, may not be aware that euthanasia is an option. Other owners may have had a prior negative experience with euthanasia. Research that allows us to determine methods to improve awareness of and accessibility to euthanasia is an important mechanism to support end-of-life planning and relieve animal suffering.

13) How do veterinary professionals communicate with pet owners to incorporate their specific needs in treatment decisions?

Cultural competency, building trust, and clear communications are essential for veterinary professionals to increase access to care in their communities.12,57 Because pet owners are the primary managers of their pets’ care, effective communication between pet owners and veterinary professionals is critical for developing sustainable achievable care plans that accommodate both the pet and their family’s needs.58,59 Improved communication between veterinarians and clients increases client’s satisfaction and trust, increases treatment compliance, and can help to reduce the threat of liability for veterinarians when combined with written documentation.60–62 Effective veterinary communication is imperative when engaging with clients in shared decision-making around treatment or euthanasia decisions58,63 and is a crucial component of the SoC treatment approach.58 Documenting and overcoming resistance to new methods of communication among practitioners is also needed. While some work has been done in this space,60,64 additional research could focus on developing methods to build effective communication skills and cultural competence among veterinary providers and students and evaluating outcomes of different communication strategies. Likewise, research could serve to provide clients with tools to enhance their communication with their veterinarians to promote informed-client consent and shared decision-making.

14) What are the obstacles to the veterinary field providing increased access to care?

The entire veterinary team, including veterinarians, veterinary technicians, veterinary students, practice managers, and client service coordinators, are all essential in advancing AVC. Therefore, approaches to AVC must consider the constraints that veterinary professionals operate within. While many private practice veterinarians are actively engaged in addressing the needs of underserved pet populations,16 there are some institutionalized practices and norms that can create barriers for veterinary care providers to increase access to care. While remediating these issues on a societal scale will take sustained effort across the field, they create obstacles to veterinary professionals as they work to overcome barriers to providing veterinary care. For instance, legal concerns about licensing and liability as well as a lack of outcome-based research in the veterinary literature are obstacles to routinely discussing a SoC options.48,58,62 Identifying practices and norms that are exclusionary and understanding how veterinary practitioners are affected would enable the field to address obstacles that limit veterinary care provision. Inviting perspectives of veterinary care providers on AVC and their perceived barriers to providing care is critical. A recent survey of veterinary practitioners by scholars at Colorado State University is one example of pilot research that describes AVC from the perspective of veterinary practitioners, citing inability of caretakers to afford treatment and a lack of providers as a central barrier to providing access to care.65 Increasing diversity within the veterinary field is likewise necessary, so that providers are more representative of the communities they serve. Another strategy is to consider what role other staff working in the veterinary field such as receptionists, veterinary assistants, or practice managers could play in making care more accessible. More research is imperative for understanding the constraints and barriers that veterinary providers face and for designing AVC approaches that are feasible.

15) How can we involve the entire veterinary community in efforts to increase AVC?

Eliminating barriers to accessing veterinary care is a multi-faceted and complex problem that must involve a dedicated effort from the entire veterinary community. The veterinary community in the US includes a wide range of interested parties: veterinarians, administrators, state boards, Veterinary Medical Associations, veterinary schools, etc. All parties play an important role in ensuring that the veterinary profession continues to operate safely and effectively. While there has been adoption of approaches that increase access to care such as SoC and telehealth, there is still not universal support across the veterinary community. Understanding the benefits of these approaches to patient, clients, and the veterinary community (Questions #3, #5, and #6) can incentivize implementation of these and other practices that increase access. Defining equitable access to care, articulating the obstacles, and defining basic standards of care (Questions #1, #14, and #8) may provide opportunities when these are barriers for involvement. Gaining buy-in from the entire community, including collaboration with animal control/humane law enforcement, public health professionals, and human service agencies, can help make AVC mainstream and encourage training and regulatory support for practices that increase access. Also, the inclusion of demographically diverse and historically marginalized perspectives in the veterinary field is imperative to help ensure representation in all practices.

16) How much would increasing use of veterinary technicians and midlevel practitioners increase access to care?

There is much to be learned about how AVC may be increased through leveraging veterinary technicians or nurses,66 and midlevel practitioners67 in the veterinary workforce. Prior work has found that higher ratios of technicians to veterinarians can increase the capacity of veterinary providers, facilitating more efficient and higher quality veterinary care.66,68 Current interest in exploring the potential role of midlevel practitioners has arisen from efforts in the human health sector to help address provider shortages.67 A ballot initiative in the state of Colorado recently authorized the creation of a midlevel practitioner, who would work under a veterinarian’s supervision, providing an opportunity to evaluate the impacts of such a role on increasing access to care. Future research could measure the potential impacts of increased utilization of veterinary technicians and the addition of a midlevel practitioner on patient outcomes, practice capacity, distribution of practitioners, operational efficiency, and the costs of treatment.

17) What are the most effective approaches for preparing veterinary students and professionals to increase AVC?

Preparing the next generation of professionals to evaluate and apply AVC strategies is a major opportunity to increase AVC across the field. Research findings from many of the questions on this list, when incorporated into veterinary and technician training, will broaden new veterinary professionals’ knowledge and skill sets in any practice setting, increase awareness of AVC, and give them the tools to implement AVC approaches. Work in this space could focus on identifying gaps in veterinary curricula,69 on developing and testing approaches to train the practical skills that are critical for veterinary students to implement a SoC, or encourage a SoC to be standard teaching in veterinary colleges as exemplified by the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges SoC Initiative, WisCares, and Tufts at Tech. As veterinary education programs adopt a curriculum promoting AVC, evaluation of the effectiveness of these systems in changing veterinary medical professionals’ perspectives and practices via research like that suggested with Questions #14 and #15 will be needed so that we can monitor and adapt veterinary medical training medicine programs accordingly.

18) How can we make veterinary care more affordable for underserved pet owners?

The cost of veterinary care increased more than 10% between July 2022 and July 2023,70 and 27.9% of households report that they are unable to pay for veterinary services.16 Practitioner satisfaction and burnout are associated with clients’ financial constraints71; therefore, addressing affordability is a matter that impacts clients and veterinary care teams alike. Research about methods to improve the affordability of veterinary care is critically needed and could include studies that describe current sustainable business models that provide affordable veterinary care.36 Addressing practice efficiency (including the roles of veterinary technicians) may also help client affordability.72 Similarly, research that tests the effectiveness of lower cost treatment options (Question #9) could expand the SoC that veterinarians provide to include options along the spectrum of affordability. Exploring and comparing a variety of mechanisms to reduce the cost of care delivery for the individual pet owner (Question #19) when combined with successful communication and evidence for effective lower cost care options will have a significant impact on improving AVC. Having more options to offer pet owners may also help alleviate burnout and distress experiences by veterinary professionals.58

19) What are sustainable structural and funding models to expand AVC?

Providing veterinary care is expensive due to high costs of real estate, equipment, supplies, testing, pharmaceuticals, insurance, and professional education.73–75 To cover these costs, fees for veterinary services are commensurately high, which prevents many traditional practices from offering services at prices that are affordable for most pet owners. Several veterinary models have emerged in response in the for-profit (Open Door Veterinary Care) and non-for-profit (Emancipet) realms.36 These existing models provide an excellent opportunity for the field to learn how current models work and to build additional models that enable veterinarians to sustainably provide veterinary services at a lower cost. Research demonstrating the feasibility and effectiveness of sustainable business models focused on different market segments would help to encourage practitioners across the field to engage in AVC practices, expanding availability of affordable services. While scholars at the Ohio State University36 have begun to address this question, it merits further attention, given new veterinary service models are regularly emerging, and there is still a need for focused research on individual models and specific approaches and their requirements for success that are viable and increase access to care.

20) How do we make the process of administering veterinary care more efficient and effective?

Addressing barriers to veterinary care requires substantial effort and resources, so it is imperative that we understand how to both improve efficiency and efficacy of AVC policies and programs. Improved efficiency relates to both the quality of care and number of patients that can be provided services without overextending these resources. Key research in this area could help to identify inefficiencies in veterinary clinic operations and test different tools to optimize the current use of time, space, and other resources.72 For instance, research could investigate the types of appointments clinics have and whether they are necessary to conduct in person so that providers could shift certain types of appointments to telemedicine, freeing up clinic space and veterinarian time. Alternately, research could be used to determine why or why not clinics are using veterinary technicians to their fullest capacity and how to do this better to provide more growth opportunities for technicians, decrease turnover, and increase job satisfaction, as well as create more time for veterinarians to see more clients and use their unique skill set to the fullest (Question #16). As more research on efficiency and efficacy related to AVC becomes available, it will equip providers with information about how strategies can be applied across policies and practices to optimize the use of veterinary resources.

Discussion

Condensing the feedback and suggestions of 462 respondents with 1,227 questions down to the 20 highest priority questions to answer to improve AVC was an illuminating effort. This modified Delphi method generated a consolidated understanding of the needs expressed by many of the professionals, stakeholders, and community members working to resolve barriers to AVC. The base knowledge extrapolated within the summaries of the 20 highest priority questions demonstrates the groundwork already completed and informs next steps and future work to address each question.

This list of questions was generated from input across the AVC community to capture perspectives from a variety of different facets of AVC. Our survey soliciting questions was dispersed across all the known major professional listservs of organizations whose work touches AVC. We intentionally convened a large group of AVC experts representing a variety of settings and disciplines for the steering committee to distribute the survey and contribute, review, and prioritize questions; however, a limitation of our approach was that we did not collect or analyze demographic information on our respondents. We recognize that there are variations and disparities in experiences and needs related to AVC. To underscore this, the first question listed in the 20 questions is a question about defining equitable AVC, which highlights the importance of considering demographics and their corresponding variations and disparities in AVC when approaching each of the proposed questions.

This is a rapidly shifting field, and there may be questions that emerge that are not on this list but have great potential to advance AVC. The survey was conducted in the latter half of 2021, and the steering committee prioritized questions through the middle of 2022. While we encourage prioritizing these 20 topics for research, we recognize that additional questions may arise over time, and that some of these key questions could become less relevant. Additionally, the time period of the study was characterized by exceptional stress on the veterinary field, caused by high demand for veterinary care and a simultaneous lack of available veterinary services to meet the demand during the COVID-19 pandemic.62 It is therefore possible that priorities were shaped by this context. Several questions related to the veterinary shortage were suggested as research topics of importance to AVC; however, while the steering committee considered these to be influential on AVC, they were topics that should be considered independently. Answering these 20 questions may complement solutions to these systemic stresses, but they are not meant to address them directly.

These questions were generated by individuals who are generally not trained in research, and therefore, the questions were not initially drafted in such a way that lends itself to concise scientific inquiry. The initial list of questions generated through the survey tended to address general concepts rather than specific research questions that could be directly investigated and tested. In addition, our process of consolidating similar questions only further generalized them into broader topics.

Because this list of priority questions presents as broad research gaps rather than specific research questions, researchers will need to further refine and focus these questions, crafting them around specific study objectives that help to inform the broader question. Within the exploring 20 questions section, we have provided a research landscape to assist in further understanding the gaps present within each question. Each of these 20 priority questions will require numerous and diverse research efforts that tackle the question from multiple dimensions. For instance, research related to the question ‘What are the most effective mechanisms to increase access in locations with little to no veterinary services?’ will vary substantially depending upon whether it is applied to a rural or urban context as urban areas with little to no veterinary services face unique and varied challenges different from rural areas without veterinary access.34 Additionally, social and cultural barriers are likely to be different in rural and urban contexts, and exploring research in both these areas will further help to reduce barriers to AVC.

Each of the questions on this list may also be approached differently based on researchers’ field, perspective, and interpretation of the question and context. The question ‘How can we make veterinary care more affordable for underserved pet owners?’ could be answered through veterinary medical research that tests the effectiveness of low-cost treatments for common illnesses. This question could also be answered through research that documents ways that veterinary practices can improve their efficiency to reduce their costs, or research that quantifies the cost savings to clients when veterinarians practice a SoC approach or how veterinary staff communicate with clients.

Because each question involves multiple threads of research, answering these questions will require experts in both qualitative and quantitative methodologies, from multiple fields, and sometimes interdisciplinary partnerships among scholars with different expertise. For instance, the question ‘How do we make euthanasia accessible if indicated?’ could include quantitative research conducted by a veterinary epidemiologist who reviews medical record data to identify the most common conditions that result in euthanasia and also include qualitative research conducted by an anthrozoologist who interviews pet owners to determine what prevents them from seeking out euthanasia. This example highlights the need for a range of experts from multiple disciplines to comprehensively answer these priority questions.

AVC is a growing concern with developing terminology, goals, and objectives. Recent work has already begun to address the themes and questions posited. For instance, research documenting outcomes of outpatient parvovirus treatment76,77 contributes to a growing body of evidence regarding ‘How do outcomes of incremental medicine and SoC approaches differ from outcomes of traditional approaches for common illnesses and injuries?’ and also contributes to our learning regarding ‘How can we make veterinary care more affordable for underserved pet owners?’ It is important to note that future work will benefit from careful examination of, and effort to build upon, prior research so as not to duplicate efforts.

Many of the questions on this list are linked, and research in one area may advance knowledge in another. For instance, research seeking to understand ‘the most effective approaches for preparing veterinary students and professionals to increase AVC’ could help to address the question ‘What are the obstacles to the veterinary field for providing increased access to care?’ Conversely, research and advancements involving one question may depend on the answers to another. A recent evaluation of communication skills curricula for veterinary students,78 which helps to answer the question ‘What are the most effective approaches for preparing veterinary students and professionals to increase AVC?’, relies upon results of research investigating ‘How do veterinary professionals communicate with pet owners to incorporate their specific needs in treatment decisions AVC?’. Overlap across these questions demonstrates the difficulty in distinguishing AVC-related issues from each other – a consequence of AVC’s complexity and the interrelated nature of issues that prevent pet owners from receiving the veterinary care they need.

Identifying the 20 highest priority questions to address AVC is not an endeavor that can be completed by one group, in this case subject-matter experts. It is possible that our approach excluded certain groups involved in AVC, and subsequently, certain types of questions may have been missed, yet we believe this initial approach captured a broad range of questions to prioritize. It is also important to recognize that AVC also involves pet owners, who may identify a different set of high priority questions. Given the geographic, social, and cultural diversity of the United States, different pet-owning populations will experience an array of factors that impact and complicate their AVC. Community leaders within these populations and the pet-owning populations themselves possess specific knowledge about access to care that will further determine the applicability of some questions as well the potential of additional barriers such as age, physical and mental health, disability, and resource limitations. We encourage further and repeated examination of priority questions from other stakeholder populations,79 especially as future research addresses and operationalizes the questions highlighted in this paper.

Conclusion

The resources available for AVC research are limited; therefore, we need to make the best use of these resources by prioritizing the areas of research where they will have the greatest impact. The purpose of this exercise was to collaboratively identify and share the 20 questions with the greatest potential to inform and advance our work if those questions were answered. One study alone will not be sufficient to solve the breath of each question, and a variety of individual projects are necessary to identify how to best resolve each of them. Therefore, it is our goal that this project will encourage academics, funders, policy makers, and practitioners in AVC to collectively focus their future research efforts and resources in areas where they could have the greatest impact, ultimately advancing AVC efforts across the country and saving more pets’ lives.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two reviewers for thoughtful feedback that improved the manuscript, Emily Dolan for reviewing the initial questionnaire and consolidating and categorizing questions, and Melanie Segal for coordinating the team and administering the survey.

Author credit statement

This study was conceptualized by Sharon Pailler. Arnold Arluke, Amanda Arrington, Kiyomi Beach, Lauren Bernstein, Jason Coe, T’ Fisher, William Frahm-Gillies, Inga Fricke, Sloane Hawes, Kendall Houlihan, Janet Hoy-gerlach, Emily McCobb, Sharon Pailler, Jennifer Scarlett, Sheila Segurson, Douglas Spiker, Apryl Steele, Jim Tedford, and Brittany Watson conducted data collection. Veronica Accornero, Sharon Pailler, and Margaret Slater completed data curation and analysis. The original draft was completed by Sharon Pailler and Molly Sumridge, with substantive input from Emily McCobb, Kiyomi Beach, Sloane Hawes, Kendall Houlihan, Janet Hoy-Gerlach, and Sheila Segurson. Margaret Slater, Apryl Steele, and Brittany Watson reviewed and provided indispensable guidance on early drafts.

Statement of ethics

All survey materials and procedures were approved by Advarra’s Institutional Review Board on October 7th, 2021 (Pro00057998).

References

| 1. | Bir C, Ortez M, Widmar NJO, Wolf CA, Hansen C, Ouedraogo FB. Familiarity and use of veterinary services by US resident dog and cat owners. Animals. 2020;10:1–27. doi: 10.3390/ani10030483 |

| 2. | Hawes SM, Hupe TM, Winczewski J, et al. Measuring changes in perceptions of access to pet support care in underserved communities. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.745345 |

| 3. | Lem M. Barriers to accessible veterinary care. Can Vet J. 2019;60:891–893. |

| 4. | LaVallee E, Mueller MK, McCobb E. A systematic review of the literature addressing veterinary care for underserved communities. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2017;20(4):381–394. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2017.1337515 |

| 5. | Kent JL, Mulley C. Riding with dogs in cars: what can it teach us about transport practices and policy? Transp Res Part A. 2017;106:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2017.09.014 |

| 6. | Morris A, Wu H, Morales C. Barriers to care in veterinary services: lessons learned from low-income pet guardians’ experiences at private clinics and hospitals during COVID-19. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.764753 |

| 7. | Hinchcliff AN, Harrison KA. Systematic review of research on barriers to access to veterinary and medical care for deaf and hard of hearing persons. J Vet Med Educ. 2022;49(2):151–163. doi: 10.3138/jvme-2020-0116 |

| 8. | Neal SM, Greenberg MJ. Putting access to veterinary care on the map: a veterinary care accessibility index. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.857644 |

| 9. | Winkley EG, KuKanich K, Nary D, Fakler J. Accessibility of veterinary hospitals for client mobility-related disabilities. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2020;256(3):333–339. doi: 10.2460/javma.256.3.333 |

| 10. | Lloyd J. Pet Healthcare in the US: Are There Enough Veterinarians? Mars Veterinary Health; 2021. https://www.marsveterinary.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Characterizing%20the%20Need%20-%20DVM%20-%20FINAL_2.24.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2024. |

| 11. | Lloyd J. Pet Healthcare in the U.S.: Another Look at the Veterinarian Workforce. Mars Veterinary Health; 2023. https://www.marsveterinary.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Characterizing-the-Need.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2024. |

| 12. | Arluke A, Rowan AN. Underdogs: Pets, People, and Poverty. The University of Georgia Press; 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvxkn5fc |

| 13. | White S. Fundamentals of HQHVSN. White S, ed. 2020.Wiley; doi: 10.1002/9781119646006.ch23 |

| 14. | Wu H, Bains RS, Morris A, Morales C. Affordability, feasibility, and accessibility: companion animal guardians with (dis)abilities’ access to veterinary medical and behavioral services during COVID-19. Animals. 2021;11(8):2359. doi: 10.3390/ani11082359 |

| 15. | Nishi NW, Collier MJ, Morales GI, Watley E. Microaggressions in veterinary communication: what are they? How are they harmful? What can veterinary professionals and educators do? J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;262(3):1–6. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.07.0412 |

| 16. | Access to Veterinary Care Coalition. Access to Veterinary Care: Barriers, Current Practices, and Public Policy. The University of Tennessee; Knoxville TN; 2018. |

| 17. | HSUS. Keeping Pets for Life. Humane Society of the United States; 2020. https://www.humanesociety.org/issues/keeping-pets-life. Accessed October 2, 2020. |

| 18. | Mueller MK, Chubb S, Wolfus G, McCobb E. Assessment of canine health and preventative care outcomes of a community medicine program. Prev Vet Med. 2018;157(20):44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2018.05.016 |

| 19. | King E, Mueller M, Wolfus G, McCobb E. Assessing service-learning in community-based veterinary medicine as a pedagogical approach to promoting student confidence in addressing access to veterinary care. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.644556 |

| 20. | Sutherland WJ, Adams WM, Aronson RB, et al. One hundred questions of importance to the conservation of global biological diversity. Conserv Biol. 2009;23(3):557–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01212.x |

| 21. | Sutherland WJ, Freckleton RP, Godfray HCJ, et al. Identification of 100 fundamental ecological questions. Gibson D, ed. J Ecol. 2013;101(1):58–67. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12025 |

| 22. | Sutherland WJ, Armstrong–Brown S, Armsworth PR, et al. The identification of 100 ecological questions of high policy relevance in the UK. J Appl Ecol. 2006;43(4):617–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01188.x |

| 23. | Sargeant JM, Brennan ML, O’Connor AM. Levels of evidence, quality assessment, and risk of bias: evaluating the internal validity of primary research. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:960957. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.960957 |

| 24. | Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;17(5):637–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x |

| 25. | Panchal AR, Cash RE, Crowe RP, et al. Delphi analysis of science gaps in the 2015 American Heart Association cardiac arrest guidelines. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(13):e008571. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008571 |

| 26. | Kobus J, Westner M. Ranking-type delphi studies in IS research: step-by-step guide and analytical extension. In: IADIS International Conference on Information Systems; Vilamoura, Algarve, Portugal; 2016. |

| 27. | Sullivan GM, Artino AR. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):541–542. doi: 10.4300/JGME-5-4-18 |

| 28. | Kunz K, Atsas S. Ensuring equitable access to public health care: two steps forward, one step back. Soc Sci J. 2013;50(4):449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2013.07.013 |

| 29. | Roberts C, Woodsworth J, Carlson K, Reeves T, Epp T. Defining the term ‘underserved’: a scoping review towards a standardized description of inadequate access to veterinary services. Can Vet J. 2023;64(10):941–950. |

| 30. | Pasteur K, Diana A, Yatcilla JK, Barnard S, Croney CC. Access to veterinary care: evaluating working definitions, barriers, and implications for animal welfare. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11:1335410. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1335410 |

| 31. | Lundahl L, Powell L, Reinhard CL, Healey E, Watson B. A pilot study examining the experience of veterinary telehealth in an underserved population through a university program integrating veterinary students. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.871928 |

| 32. | Poss JE, Everett M. Impact of a bilingual mobile spay/neuter clinic in a U.S./Mexico border city. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2006;9(1):71–77. doi: 10.1207/s15327604jaws0901_7 |

| 33. | Mattson K. Veterinary medicine may face increasing challenges around language barriers. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019;255(10):1083. doi: 10.2460/javma.255.10.1083 |

| 34. | Bunke L, Harrison S, Angliss G, Hanselmann R. Establishing a working definition for veterinary care desert. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;262(1):1–8. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.06.0331 |

| 35. | Blackwell MJ, O’Reilly A. Access to veterinary care – a national family crisis and case for one health. Adv Small Anim Care. 2023;4(1):145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.yasa.2023.05.003 |

| 36. | Garabed R, Overcast M, Behmer V, Bryant E, Heredia K, Jones A. Business Models Used to Improve Access to Veterinary Care. Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Columbus OH; 2022. |

| 37. | Arrington A, Markarian M. Serving pets in poverty: a new frontier for the animal welfare movement. Sustain Dev Law Policy. 2017;18(1):40–43. |

| 38. | Jenkins JL, Rudd ML. Decolonizing animal welfare through a social justice framework. Front Vet Sci. 2022;8:787555. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.787555 |

| 39. | Decker Sparks JL, Camacho B, Tedeschi P, Morris KN. Race and ethnicity are not primary determinants in utilizing veterinary services in underserved communities in the United States. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2018;21(2):120–129. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2017.1378578 |

| 40. | Cammisa H, Hill S. Payment options: an analysis of 6 years of payment plan data and potential implications for for-profit clinics, non-profit veterinary providers, and funders to access to care initiatives. Frontiers. 2022;9:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.895532 |

| 41. | Hohenhaus AE. Improving access to advanced veterinary care for rescued cats and dogs. J Feline Med Surg. 2023;25(12):1098612X231211755. doi: 10.1177/1098612X231211755 |

| 42. | Moss LR, Hawes SM, Connolly K, Bergstrom M, O’Reilly K, Morris KN. Animal control and field services officers’ perspectives on community engagement: a qualitative phenomenology study. Animals. 2022;13(1):68. doi: 10.3390/ani13010068 |

| 43. | Reese L, Li X. Animal welfare deserts: human and nonhuman animal inequities. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10:1189211. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1189211 |

| 44. | Covner AL, Ekstrom H, Kalaf N, Sherman B. Creating evidence driven practices to enhance human care services for unhoused and low-income pet owners. J Nur Healthc. 2022;7(3):1–11. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1761858/v1 |

| 45. | Hawes SM, Hupe T, Morris KN. Punishment to support: the need to align animal control enforcement with the human social justice movement. Animals. 2020;10:1–8. doi: 10.3390/ani10101902 |

| 46. | Cardona A, Hawes SM, Cull J, et al. Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation perspectives on Rez dogs on the Fort Berthold reservation in North Dakota, U.S.A. Animals. 2023;13(8):1422. doi: 10.3390/ani13081422 |

| 47. | Pugliese M, Voslarova E, Biondi V, Passantino A. Clinical practice guidelines: an opinion of the legal implication to veterinary medicine. Animals. 2019;9(8):1–13. doi: 10.3390/ani9080577 |

| 48. | Stull JW, Shelby JA, Bonnett BN, et al. Barriers and next steps to providing a spectrum of effective health care to companion animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253(11):1386–1389. doi: 10.2460/javma.253.11.1386 |

| 49. | Haworth D. The role of incremental care. In: Lowell Ackerman (Editor) Pet-Specific Care for the Veterinary Team. John Wiley & Sons; 2021:43–45. |

| 50. | Englar RE. The gold standard, standards of care, and spectrum of care: an evolving approach to diagnostic medicine. In: Ryane E. Englar, & Sharon M. (Editor) Dial Low–Cost Veterinary Clinical Diagnostics. 1st ed. Wiley; 2023. doi: 10.1002/9781119714521 |

| 51. | Pailler S, Dolan ED, Slater MR, Gayle JM, Lesnikowski SM, DeClementi C. Owner-reported long-term outcomes, quality of life, and longevity after hospital discharge following surgical treatment of pyometra in bitches and queens. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2022;260(S2):S57–S63. doi: 10.2460/javma.20.12.0714 |

| 52. | Pailler S, Slater MR, Lesnikowski SM, et al. Findings and prognostic indicators of outcomes for bitches with pyometra treated surgically in a nonspecialized setting. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2022;260(S2):S49–S56. doi: 10.2460/javma.20.12.0713 |

| 53. | McCobb E, Dowling-Guyer S, Pailler S, Intarapanich NP, Rozanski EA. Surgery in a veterinary outpatient community medicine setting has a good outcome for dogs with pyometra. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2022;260(S2):S36–S41. doi: 10.2460/javma.21.06.0320 |

| 54. | Anderson S, Stevenson M, Boller M. Pet health insurance reduces the likelihood of pre-surgical euthanasia of dogs with gastric dilatation-volvulus in the emergency room of an Australian referral hospital. N Z Vet J. 2021;69(5):267–273. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2021.1920512 |

| 55. | Boller M, Nemanic TS, Anthonisz JD, et al. The effect of pet insurance on presurgical euthanasia of dogs with gastric dilatation-volvulus: a novel approach to quantifying economic euthanasia in veterinary emergency medicine. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:590615. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.590615 |

| 56. | Benson J, Tincher EM. Cost of care, access to care, and payment options in veterinary practice. Vet Clin N Am – Small Anim Pract. 2024;54(2):235–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2023.10.007 |

| 57. | Alvarez EE, Gilles WK, Lygo-Baker S, Howlett B, Chun R. How to approach cultural humility debriefing within clinical veterinary environments. J Vet Med Educ. 2021;48(3):256–262. doi: 10.3138/jvme.2019-0039 |

| 58. | Brown CR, Garrett LD, Gilles WK, et al. Spectrum of care: more than treatment options. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2021;259(7): 712–717. doi: 10.2460/javma.259.7.712 |

| 59. | Brown CR, Edwards S, Kenney E, et al. Family quality of life: pet owners and veterinarians working together to reach the best outcomes. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;261(8):1238–1243. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.01.0016 |

| 60. | Janke N, Coe JB, Bernardo TM, Dewey CE, Stone EA. Pet owners’ and veterinarians’ perceptions of information exchange and clinical decision-making in companion animal practice. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0245632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245632 |

| 61. | Kanji N, Coe JB, Adams CL, Shaw JR. Effect of veterinarian-client-patient interactions on client adherence to dentistry and surgery recommendations in companion-animal practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012;240(4):427–436. doi: 10.2460/javma.240.4.427 |

| 62. | Babcock SL. How do veterinarians mitigate liability concerns with workforce shortages? J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;262(1): 145–151. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.06.0341 |

| 63. | Christiansen SB, Kristensen AT, Lassen J, Sandøe P. Veterinarians’ role in clients’ decision-making regarding seriously ill companion animal patients. Acta Vet Scand. 2016;58(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13028-016-0211-x |

| 64. | Janke N, Coe JB, Bernardo TM, Dewey CE, Stone EA. Use of health parameter trends to communicate pet health information in companion animal practice: a mixed methods analysis. Vet Rec. 2022;190(7):e1378. doi: 10.1002/vetr.1378 |

| 65. | Niemiec R, Champine V. Colorado Veterinary Professional Survey: Summary of Results. 2023. https://sites.warnercnr.colostate.edu/animalhumanpolicy/wp-content/uploads/sites/171/2023/10/AHPC-Veterinary-Professional-Survey-Results.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2024. |

| 66. | Shock DA, Roche SM, Genore R, Renaud DL. The economic impact that registered veterinary technicians have on Ontario veterinary practices. Can Vet J Rev Veterinaire Can. 2020;61(5):505–511. |

| 67. | Kogan LR, Stewart SM. Veterinary professional associates: does the profession’s foresight include a mid-tier professional similar to physician assistants? J Vet Med Educ. 2009;36(2):220–225. doi: 10.3138/jvme.36.2.220 |

| 68. | Fanning J, Shepherd AJ. Contribution of veterinary technicians to veterinary business revenue, 2007. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2010;236(8):846. doi: 10.2460/javma.236.8.846 |

| 69. | Smith SM, George Z, Duncan CG, Frey DM. Opportunities for expanding access to veterinary care: lessons from COVID-19. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:804794. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.804794 |

| 70. | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2024. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.t02.htm. Accessed February 14, 2024. |

| 71. | Kipperman BS, Kass PH, Rishniw M. Factors that influence small animal veterinarians’ opinions and actions regarding cost of care and effects of economic limitations on patient care and outcome and professional career satisfaction and burnout. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;250(7):785–794. doi: 10.2460/javma.250.7.785 |

| 72. | Ouedraogo FB, Weinstein P, Lefebvre SL. Increased efficiency could lessen the need for more staff in companion animal practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2023;261(9):1357–1362. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.03.0163 |

| 73. | Bain B. Employment, starting salaries, and educational indebtedness of year 2019 graduates of US veterinary medical colleges. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2020;257(3):292–297. doi: 10.2460/javma.257.3.292 |

| 74. | Bain B, Ouedrago F, Hansen C, Radich R, Salois M. Economic State of the Veterinary Profession. Veterinary Economics Division, AVMA; 2020:1–60. Accessed August 23. |

| 75. | Block G. A new look at standard of care. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;252(11):1343–1344. doi: 10.2460/javma.252.11.1343 |

| 76. | Sarpong KJ, Lukowski JM, Knapp CG. Evaluation of mortality rate and predictors of outcome in dogs receiving outpatient treatment for parvoviral enteritis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2017;251(9):1035–1041. doi: 10.2460/javma.251.9.1035 |

| 77. | Venn EC, Preisner K, Boscan PL, Twedt DC, Sullivan LA. Evaluation of an outpatient protocol in the treatment of canine parvoviral enteritis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2017;27(1):52–65. doi: 10.1111/vec.12561 |

| 78. | Van Gelderen (Mabin) I, Taylor R. Developing communication competency in the veterinary curriculum. Animals. 2023;13(23):3668. doi: 10.3390/ani13233668 |

| 79. | Fleming PJ, Stone LC, Creary MS, et al. Antiracism and community-based participatory research: synergies, challenges, and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(1):70–78. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.307114 |

Appendix 1. Survey

The ASPCA is conducting a survey of people whose work helps to improve access to veterinary care (AVC) for people in their communities. We need your help to figure out the most important questions in AVC that do not have answers yet. Those questions, if answered, would greatly improve the work you do. The questions, if answered, would help you make huge leaps in increasing access to care for pets.

What do we mean when we say AVC? For this survey, AVC means any work that makes veterinary care more universal and equitable and considers individual pet and family circumstances with compassion and respect, to improve welfare and decrease suffering. Please keep this definition in mind when you are thinking about what questions you think would have the greatest potential to improve AVC, if you knew the answer.

Please use this survey form to think about the questions you need answers to. When thinking about your questions, ask yourself:

- – What information do you wish you had about improving AVC?

- – What do you need to know to be better able to increase AVC for people and pets in your community?

- – What information would make your work in AVC easier?

- – What questions do you have about the work others are doing in AVC?

We welcome questions about any and all aspects and elements of AVC from the client, patient, and veterinary staff perspectives. Your questions could relate to veterinary medical interventions; outreach approaches and client communications; program operations, delivery, and impact; diversity and inclusion; social; cultural; economic; legal; or policy aspects of AVC. Any question related to improving AVC will be helpful to us. The more specific the better!

Here are a few examples:

- – Does increasing AVC improve clients’ mental or physical health?

- – Does pets’ response to treatment improve when clients are given illustrated treatment instructions?

Our plan is to take your questions and use research to try and find the answers. This is your chance to influence research in AVC! Please help us identify the most important questions in AVC so that we can focus future research on finding the answers.

Your participation in this survey is voluntary. We expect the survey will take up to 20 min of your time to complete. There are no risks or benefits for your participation, but the questions identified may help improve AVC programs and activities. Your responses will be kept confidential.

To thank you for your time, you will have the option to enter your email at the end of the survey for a chance to win one of five Amazon gift cards worth $75. (Please note: ASPCA employees are not eligible for the gift cards).

If you have any questions, please contact XXXXXXX, Research Director, ASPCA at XXXXXXXXX

Clicking on the button to continue constitutes my consent to participate in this survey.